Kursthemen

-

Video introduction: EduBoxes – Virtual Intercultural Teams

Topics

- Background

- How to use the trainer manual

- The learning objective of the online course

- The learning journey

- The approach

- Structure of the trainer manual

- Copyrights

-

Topics

- Intercultural teaching and learning – developing intercultural competence

- How intercultural teaching and learning works

- Didactic concepts of intercultural learning and teaching

- Summary

The ability to work effectively in intercultural teams has been a key competence for a considerable time. Now, the increasing necessity (and opportunity) to work in these teams in a virtual environment has made these competences even more crucial.

Teaching and learning virtual intercultural teamwork take place in a wide range of disparate teaching and learning contexts. In addition to classic forms of in-person training, various digital forms of teaching and learning have now found their way into everyday professional education, continuing education and university life, which can be summarised by the term "e-learning". This includes all forms of learning that are supported by digital media (Bolten 2007c, p. 755). Examples here are hybrid teaching, online synchronous and asynchronous teaching, flipped classroom, blended learning, etc. The different forms of E-learning can be categorised as follows:

- E-learning: Learning is focused on pure assimilation of information and is instructor-centered;

- Interacting: Teaching and learning occurs via learning platforms such as Moodle;

- Collaborating: Learners collaborate virtually through the use of certain tools, which fall under the umbrella term ‘Web 2.0’ (Gröhbiel & Schiefner 2006, p. 7).

We have designed the Virtual Intercultural Teams (ViTeams) Edubox as an online self-learning module. From the categories above, it corresponds to the teaching & learning type ‘e-learning by interacting’ and has the following requirements for teachers/trainers and learners:

Requirements for learners:

In this e-learning programme, learners will process predefined relevant information according to a specific pattern. Based on (self-)reflection tasks, learners are provided with various options to enable them to implement and process the information with the help of a learning diary and a learning review.

Requirements for instructors:

Teachers are not always necessary. Learners process the information based on predefined possible learning paths. In a support role, teachers or instructors for that matter can accompany the learning process as learning facilitators. Instructors can enable learners to communicate with each other via forums and chats (peer-to-peer), but also to communicate with the instructors themselves. In this way learners can receive timely individual feedback on their performance (in connection with their learning diary/learning review).

E-learning by interacting can partly suffer from the phenomenon of the lonely learner because the learning exclusively consists of self-learning phases, in which there is either no direct contact with teachers and other learners or this communication occurs after the event. To address this shortcoming, we have designed our online self-learning course Intercultural Communication (InCom) for a mixed form of face-to-face and online teaching, i.e., as a blended learning seminar or training programme. For this purpose, we have developed a blended-learning based learner support system. This manual is intended to assist with the methodological and didactical implementation of this support system.

The conception of the course Intercultural Communication (InCom) in the form of blended learning combines in-person learning and e-learning by interacting in such a way that the advantages of each learning form are maximised while the disadvantages are minimised: Self-directed, location-independent and temporally flexible learning is enabled via an online learning management system (for example Moodle), while practical exercises and a deepening of understanding occurs through exchanges with both peer learners and teachers during the in-person learning phases. However, the in-person and self-learning phases do not exclude each other. The in-person phases, for example, can also leverage digital tools such as Padlet, Menti, Miro, etc., including the use of the InCom course. The online self-learning course InCom is designed to develop intercultural competence and provides the following content that can be used for blended learning:

Learning outcome or competencies: Drawing on current theories, learners analyse intercultural interactions and communication processes in social and professional contexts. Based on these theories, they learn to develop a common basis of understanding and a shared code system with their communication partners.

Content: After examining a range of theories, concepts and models, an open and interactive concept of culture is proposed. This involves viewing culture in its extended and open form whilst applying the approach of multi-collectivity. Since this view of culture focusses on interactions, the concept of communication itself is defined and models for the analysis of communication processes are explained. Culture is elaborated as a product of communication and vice versa. Factors that influence the communication process are reflected upon. These could be, for example, perceptual habits due to previous experiences and, connected to this, expectations, stereotyping, cultural perspectives, and cultural knowledge (implicit and explicit).

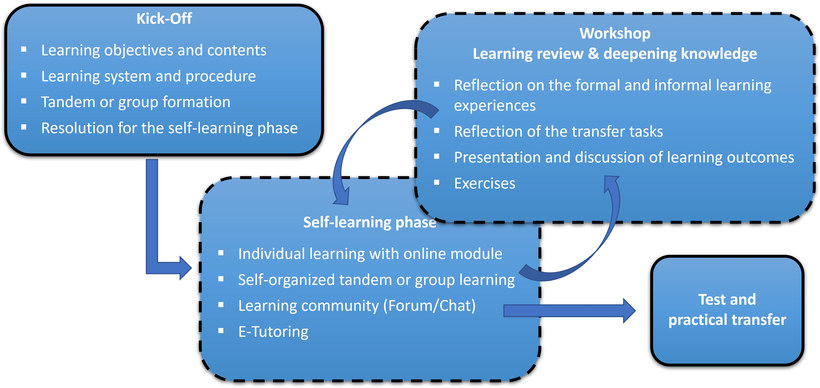

In addition to content and learning support, successful learning also requires the process to be structured in a way that enables blended learning, as shown in Figure 1:

Figure: Blended learning concept of the online course 'Virtual intercultural teams'

Source: Yildirim-Krannig, Yeliz (2020)

The learning process could be structured as follows:

- Kick-Off (online or in person)

- Online self learning phase

- In-person learning phase (workshops)

Kick-Off (online or in person)

A kick-off seminar is designed to "pick up" the learners at their current knowledge level. It ensures that everyone shares an understanding of the learning objectives and content, allows participants to get to know each other, and ensures transparency regarding the teachers’ and learners’ expectations and experiences. Uncertainties, questions, etc. can be raised here.

The content for the self-learning phase in the online self-learning module and the processing time(s) available to the learners is decided by the trainer/teacher. Additionally, the teacher can determine whether learning groups work together on the learning units, exchange information on the tasks, benefit from different perspectives, knowledge, and experiences (peer-to-peer) or learn as individual learners. In order to monitor whether learning objectives are being fulfilled, the teacher could ask students to submit their edited learning diaries. This works well since learning diaries usually clearly document individual learning processes.

The online self-learning phase

The online self-study module ViTeams consists of 9 learning units. The learning units are each structured in such a way that what is learned is both reflected upon and applied during specific tasks. Learning content is provided in a variety of forms. For example, this could be texts, videos, or web links to external content. The tasks require the application of theories and models to case studies, images, or videos. They encourage reflection on learners’ own experience, expectations as well as perceptual habits etc. The teacher decides which content will be learned online in the self-learning phase and which content they wish to teach or deepen during in-person encounters.

The online self-learning phase can be facilitated through forums and chats that enable an exchange both within the learning group but also with trainers/teachers via a learning platform such as Moodle or similar.

Workshops

During the in-person learning phase (workshop/training/seminar), the topics and content that were not part of the self-learning phase can be taught in a practice-oriented manner. The attendance phase can also be used for practice-oriented repetition and consolidation of what has been learned. Which content is repeated or treated in more detail in a face-to-face environment will be contingent upon the learners’ individual learning conditions and progress. To this end, the learning diaries can be used to determine whether topics require repetition or consolidation.

The classroom events are to be seen as a learning workshop in which learners can work together on topics, experience team building measures, contribute their perspectives, and benefit from the knowledge and experience of others. The role of the teacher changes here from giving input to moderating and coaching. Learning here is partly instructional and partly interactive, according to the didactic diamond that we will introduce in CHAPTER 2.3.

The teacher might also embrace a sustainable workshop design by maintaining the seminar room as a paper free space. For example, participants could work with a Moodle platform where participants can access materials (PDFs), video links etc. via their digital devices. In addition, digital tools such as Padlet (digital flipchart for collating group findings from face-to-face events), Mentimeter (brainstorming, association exercises, opinion polling etc.), Miro (joint case study analysis, mapping of results) Kahoot (online quiz) etc. could be used. All results could then be made available to learners on the Moodle platform, for example.

We recommend starting each classroom session with a brief review of what has been learned so far and concluding with an evaluation of progress towards the learning objective, i.e., ‘What did we intend to do and what did we accomplish?’).

Teaching and learning goals for virtual intercultural teamwork can only be achieved by combining a variety of methods to stimulate holistic learning (cognitive, affective, and conative learning goals). We recommend a practical application of the learning content by using virtual intercultural simulation games (Megacities or Bilangon from interculture.de) or by carrying out project work in intercultural teams (EduBox Design Thinking).

For a better understanding of holistic learning design and which approaches should guide your actions, we recommend studying CHAPTER 2.2. For us, a specific understanding of intercultural competence is a prerequisite for successful teaching and learning. You can read about this kind of understanding in CHAPTER 2.1.

The entire manual is based on the epistemological assumptions of constructivism and the resulting didactic approaches to teaching and learning.

-

In addition to the case studies, activities, and tasks designed to review insights gained within the online learning course, supplementary teaching and training materials are also provided here for selected topics. This particular set of materials is tailored specifically to participants employed by small and medium-sized businesses (SMEs) or non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

Topics

- Virtual teamwork in my work environment

- Culture and interculturality, a plea for an open and dynamic approach

- Developing from a group into a virtual team

- Roles and role expectations

- Creating mutuality in intercultural and interdisciplinary virtual teams

- Key challenges of virtual intercultural teams

- Negotiating an e-culture for virtual teams

- My competences for working in a virtual intercultural team

-

- Aebli, H. (2011). Zwölf Grundformen des Lehrens: Eine Allgemeine Didaktik auf psychologischer Grundlage. Stuttgart: Klett Cotta.

- Arnold, R. (2015). Systemtheoretische Grundlagen einer Ermöglichungsdidaktik. In R. Arnold & I. Schüssler (Eds.), Ermöglichungsdidaktik. Erwachsenenpädagogische Grundlagen und Erfahrungen. Grundlagen der Berufs- und Erwachsenenbildung, Vol. 35 (pp. 14-36). Baltmannsweiler: Schneider Verlag Hohengehren

- Arnold, R., Krämer-Stürzl, A., & Siebert, H. (2011). Dozentenleitfaden: erwachsenen-pädagogische Grundlagen für die berufliche Weiterbildung. Berlin: Cornelsen.

- Baumgartner, P. & Bergner, I. (2017). Lebendiges Lernen gestalten. 15 strukturelle Empfehlungen für didaktische Entwurfsmuster in Anlehnung an die Lebenseigenschaften von Christopher Alexander. In K. Rummler (Ed.), Lernräume gestalten – Bildungskontexte vielfältig denken. Medien in der Wissenschaft 67 (pp. 163-173). Münster, New York: Waxmann.

- Blumer, H. (1969). Symbolischer Interaktionismus. Aufsätze zu einer Wissenschaft der Interpretation. Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp.

- Bolten, J. (2007a). Was heißt "Interkulturelle Kompetenz?" Perspektiven für die internationale Personalentwicklung. In V. Künzer, & J. Berninghausen (Eds.), Wirtschaft als interkulturelle Herausforderung (pp. 21-42). Berlin: IKO.

- Bolten, J. (2007b). Interkulturelle Kompetenz. Erfurt: Landeszentrale für politische Bildung.

- Bolten, J. (2007c). Interkulturelle Kompetenz im E-Learning. In J. Straub, A. Wiedemann, & D. Wiedemann (Eds.), Handbuch interkultureller Kommunikation und Kompetenz (pp. 755-762). Stuttgart: J. B. Metzler.

- Bolten, J. (2011). Unschärfe und Mehrwertigkeit: "Interkulturelle Kompetenz" vor dem Hintergrund eines offenen Kulturbegriffs. In W. Dreyer (Ed.), Perspektiven interkultureller Kompetenz (pp. 55-70). Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Bolten, J. (2012). Interkulturelle Kompetenz. Erfurt: Landeszentrale für politische Bildung.

- Bolten, J. (2015). Einführung in die interkulturelle Wirtschaftskommunikation. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Bolten, J. (2016a). Interkulturelle Kompetenz – eine ganzheitliche Perspektive. Polylog, Sonderheft "Interkulturelle Kompetenz in der Kritik", 2016 (36), pp. 23-38 (Wien).

- Bolten, J. (2016b). Interkulturelle Trainings neu denken. Interculture Journal, 15 (26), pp. 75-91 (Berlin: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag).

- Bolten, J. (2020). Lehr-/Lernmethoden haben kulturelle Kontexte. [Vorlesung, 14.5.2020] https://www.db-thueringen.de/receive/dbt_mods_0042826. Digitale Bibliothek Thüringen.

- Bower, G. H., & Hilgard, E. R. (1983). Theorien des Lernens. Stuttgart, Klett Cotta.

- Deardorff, D. K. (2006). Interkulturelle Kompetenz – Die Schlüsselkompetenz des 21. Jahrhunderts? Bertelsmann Stiftung/Fondazione Cariplo (Ed.), Interkulturelle Kompetenz – Die Schlüsselkompetenz im 21. Jahrhundert? Thesenpapier der Bertelsmann Stiftung auf Basis der Interkulturellen-Kompetenz-Modelle von Dr. Darla K. Deardorff. Gütersloh: Verlag Bertelsmannstiftung. https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/fileadmin/files/BSt/Presse/imported/downloads/xcms_bst_dms_30236_30237_2.pdf. (Zugriff am 13.6.2024)

- Dewey, J. (1910). How we think. Lexington/Massachusetts: D.C. Heath & Comapny.

- Gröhbiel, U., & Schiefner, M. (2006). Die E-Learning-Landkarte – eine Entscheidungshilfe für den E-Learning-Einsatz in der betrieblichen Weiterbildung. In Hohenstein, A., & Wilbers, K. (Eds.), Handbuch E-Learning, 17. Ergänzungslieferung, 3.11 (pp. 1-20).

- Gudjons, H., & Traub, S. (2020). Pädagogisches Grundwissen. Überblick – Kompendium – Studienbuch. Bad Heilbrunn: Julius Klinkhardt.

- Holtz, K. L. (2008). Einführung in die systemische Pädagogik. Heidelberg: Carl Auer.

- Keller, R., Knoblauch, H., & Reichertz, J. (2013). Der Kommunikative Konstruktivismus als Weiterführung des Sozialkonstruktivismus. Eine Einführung in den Band. In R. Keller, H. Knoblauch, & J. Reichertz (Eds.), Kommunikativer Konstruktivismus (pp. 9-21). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- KMK (2007). Handreichung für die Erarbeitung von Rahmenplänen der Kultusministerkonferenz und ihre Abstimmung mit Ausbildungsordnungen des Bundes für anerkannte Ausbildungsberufe. Sekretariat der Kultusministerkonferenz, Referat Berufliche Bildung und Weiterbildung. https://www.kmk.org/fileadmin/veroeffentlichungen_beschluesse/2007/2007_09_01-Handreich-Rlpl-Berufsschule.pdf (Zugriff am 13.9.2022)

- Kriegel-Schmidt, K. (2012). Interkulturelle Mediation. Plädoyer für ein Perspektiven-reflexives Modell (Dissertation, Universität Jena 2011). Münster: LIT.

- Locke, J. (1689). An essay concerning human understanding. Eine Abhandlung über den menschlichen Verstand. Ditzingen: Reclam.

- Lüsebrink, H.-J. (2008). Interkulturelle Kommunikation. Interaktion, Fremdwahrnehmung, Kulturtransfer. Stuttgart: J. B. Metzler.

- Mead, G. H. (1934). Geist, Identität und Gesellschaft. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Pfeiffer, W. (1993). Kompetenz. In W. Pfeiffer, Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Deutschen. Berlin: Academie.

- Rathje, S. (2006). Interkulturelle Kompetenz – Zustand und Zukunft eines umstrittenen Konzepts. Zeitschrift für interkulturellen Fremdsprachenunterricht, 11 (3). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237349080_Interkulturelle_Kompetenz-Zustand_und_Zukunft_eines_umstrittenen_Konzepts (Zugriff am 28.6.2024)

- Rathje, S. (2018). Gemeinschaft stiften – Aber wie? Wie Multikollektivität Stiftungen helfen kann, das Richtige zu tun. In Stiftung & Sponsoring (Ed.), Rote Seiten 06.18 (pp. 1-13). Berlin: Erich Schmidt Verlag.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341569135_Gemeinschaft_stiften_-_Aber_wie_Wie_Multikollektivitat_Stiftungen_helfen_kann_das_Richtige_zu_tun

- Reich, K. (1998). Die Ordnung der Blicke. Perspektiven des interaktionistischen Konstruktivismus. Vol. 2: Beziehung und Lebenswelt. Weinheim: Beltz.

- Reich, K. (2010). Systemisch-konstruktivistische Didaktik. Weinheim: Beltz.

- Reich, K. (2012). Konstruktivistische Didaktik. Weinheim: Beltz.

- Roth, H. (1971). Pädagogische Anthropologie. Entwicklung und Erziehung. Vol. 1. Hannover: Hermann Schrödel.

- Schütz, A., & Luckmann, T. (1979). Strukturen der Lebenswelt. Vol. 1, Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp.

- Schütz, A., & Luckmann, T. (2003). Strukturen der Lebenswelt. Konstanz: UVK.

- Siebert, H. (2005). Pädagogischer Konstruktivismus. Lernzentrierte Pädagogik in Schule und Erwachsenenbildung. München: Oldenbourg.

- Yildirim-Krannig, Y. (2014). Kultur zwischen Nationalstaatlichkeit und Migration. Plädoyer für einen Paradigmenwechsel. (Dissertation, Universität Jena 2013, Reihe Kultur und soziale Praxis). Bielefeld: transcript.