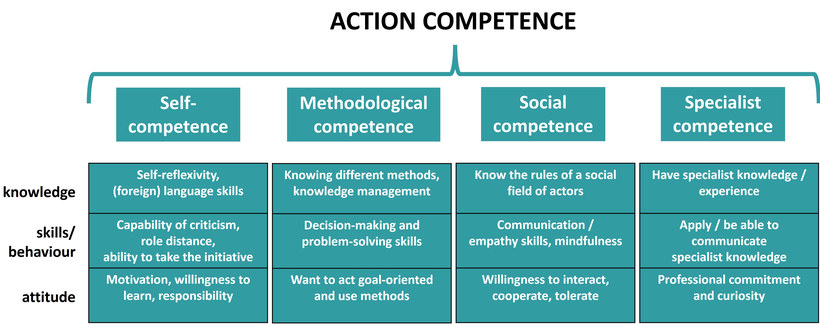

Intercultural learning and the term "intercultural competence" in particular is considered to be a key competence of the 21st century (Deardorff 2006; Lüsebrink 2008a). What we understand by the term intercultural competence, especially the term "competence", varies from academic discipline to academic discipline. Our approach to the term competence stems from the etymology of the word, which explains its origin and meaning. The term competence is a borrowed from the Latin "competentia" for coincidence, symmetry, analogy, as well as affiliation and competence. The use of the noun in Latin and in German follows the Latin verb "competere", to meet, to bring together (Pfeifer 1993). Accordingly, competence is about bringing something together. Essentially, three domains are brought together when it comes to competent action. These three domains are knowledge (cognitive level), attitude (affective level), and the skills/abilities/behaviours (conative level). All three areas are always brought together in relation to four sub-competencies: self (personal) competence, strategic (methodological) competence, social competence and specialist (technical/professional) competence.

- Self (or personal) competence: A person must develop his or her own world and self-image, represent this to the outside world and think reflectively about others. Personal competence is closely linked to the other competencies, since a person can only act according to his or her own sense of responsibility if he or she has knowledge about the decision-making process, if he or she has methods of finding solutions, and if he or she has the social ability to do so in cooperation with others.

- Strategic (or methodological) competence: Strategic competence can be described as a component skill. It is necessary to acquire knowledge and to deal with it adequately. Solutions to problems must be planned, means for their execution must be provided, ways of solving problems must be worked out and results must be reflected upon. Appropriate methods help to structure knowledge, to order it, to link it and thus to move from knowledge to action. This includes the ability to learn how to learn, and to proactively and independently further learning processes.

- Social competence: Action always takes place in a social space, usually in interaction with others. Action is action between people. Social competence means putting ourselves into social interactions, while achieving a balance between adaptation and preserving our own identity. The ability to engage with others, take on tasks in roles and groups, allow the validity of others, but also to discern when to assert ourselves at appropriate moments are central aspects of social competence.

- Specialist (or technical/professional) competence: The professional actor must have appropriate specialized knowledge so that he is in a position to make assessments and act in appropriate areas. To acquire this competence, one needs extensive knowledge of the relevant area as well as the ability and willingness to acquire further knowledge. This knowledge must also be evaluated and reflected upon.

Source: Bolten, 2007a, p. 86ff.

The division into these sub-competencies goes back to Roth (1971) and still represents an important orientation framework for the development of educational plans.

Action Competence Model

Source: Based on Bolten, 2007a, pp. 27f.

Click on the image for a larger view

The theoretical construct “competence" is made up of a variable number of components, each of which includes a person’s complex characteristics, personality, stores of knowledge and abilities/ skills. These can be brought to bear on a scenario in a manner that is adapted to the particular situation. The competence areas of self-competence, strategic competence, social competence, and specialist competence are - in the sense of competere – interrelated and in fact inseparable. All areas of competence merge into one another and exert their influence when we act. The components flow into our actions to varying degrees depending on the situation. In this way they come to together to form action competence (Bolten 2012, p. 166).

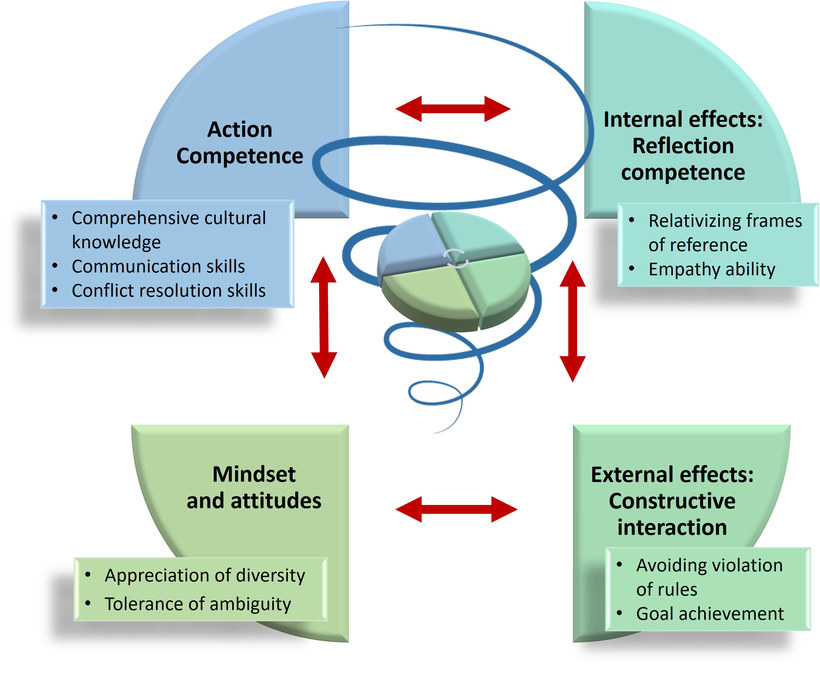

Intercultural competence is characterised through the interdependent relationship between cognitive, affective, and conative competencies and is therefore a synergetic product of a permanent interplay of partial competencies. In terms of learning theory, it is assumed that a sequence of processes takes place at the levels of attitude, knowledge and behaviour and that intercultural competence continues to develop in the form of a spiral (Deardorff 2006, p. 21).

Spiral of learning intercultural competence

Source: Based on Deardorff’s intercultural competence model, Deardorff 2006, p. 21

Click on the image for a larger view

The development of intercultural competence is therefore complex, multidimensional, and multifaceted with a differing mix of skill components becoming necessary in each specific intercultural situation. For the acquisition of intercultural competence, this means a continuous dynamic process along the four dimensions attitude, knowledge & understanding, competence to reflect (internal influence), competence to interact (external influence), which runs in different dimensions and accumulates into a spiral. The more dimensions that are reached and the more often they are passed through, the higher the degree of intercultural competence.

This process model of intercultural competence considers both personal and interpersonal levels of intercultural interaction. "A person acts in a situation not only from within him/herself but also as a result of interactional relations with his/her co-actors. This reciprocity generates its own dynamics that are borne out of the situation [...]" (Bolten 2016a, p. 26; translated).

If we follow this approach (cf. Deardorff 2006; Rathje 2006; Bolten 2007a) in relation to the process-oriented nature of intercultural competence and combine this with learning theory, then intercultural competence can be said to be the synergetic outcome of the interplay and interdependence between the four partial competencies. Competence can be achieved through context-related learning processes on the levels of attitude, knowledge, and behaviour. Context-related learning processes involve dynamic, interactive situations, the path and result of which cannot be predicted.

Intercultural competence is therefore a multi-construct, which can be understood as a learning process amid the interaction of sub-competencies and dimensions. The process and learning character of intercultural competence suggests that intercultural competence that is the same in every intercultural situation does not exist, but that there is a flexible application of competences and learning depending on the context and situation.

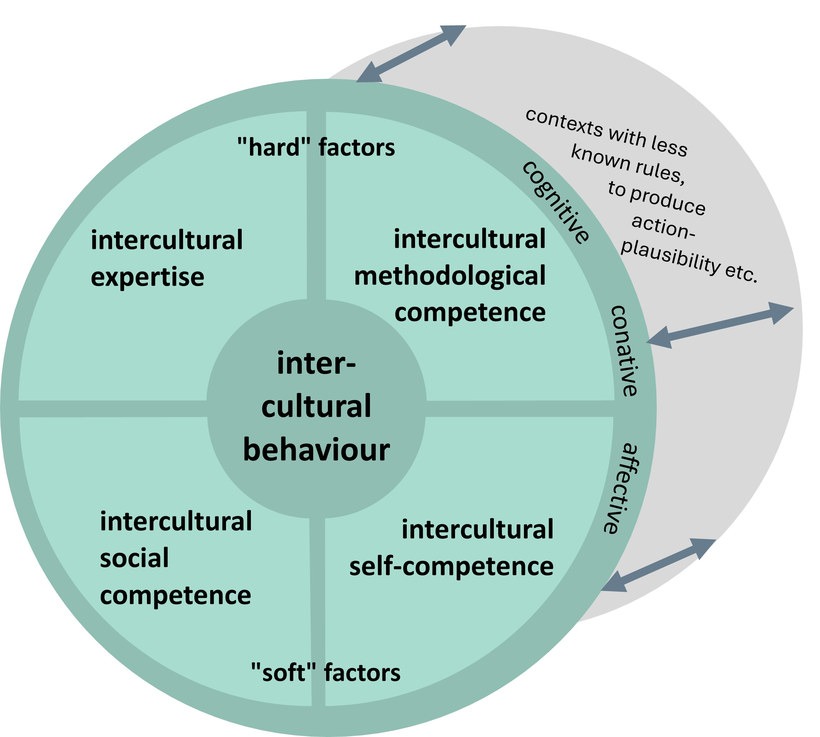

Since the characteristics of intercultural competence described here can be classified in general competence models, it can be concluded that intercultural competence cannot be a purely social competence (soft skills) or even an independent competence in the sense of a fifth sub-area of action competence. The term competence involves the skill of transferring, specifically the ability to transfer skills to intercultural interaction situations (Bolten, 2015, p. 193f.).

Intercultural action competence as a transfer competence

Source: Bolten, 2015, p. 193. Graphic recreated by Vera Harder.

Click on the image for a larger view

The difference between general action competence and intercultural action competence lies in the inherent degree of challenge involved. In intercultural scenarios, situations are characterized by an increased degree of uncertainty of action (ibid.).

In order to understand what is meant by uncertainty of action, we can turn to our understanding of interculturality. In intercultural competence, we are always faced with the implementation of a variety of different competences between cultures.

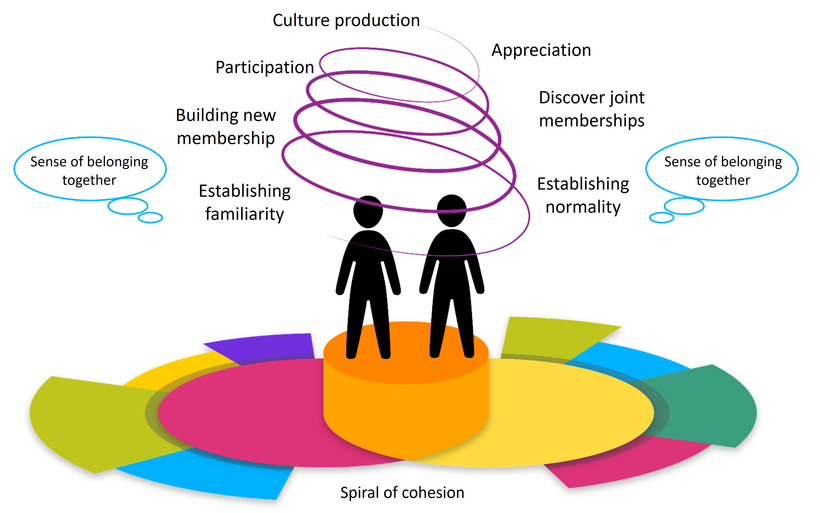

Our understanding of interculture is based on a paradigm of difference. This approach emphasizes the fact that people have affiliations to different groups (collectives), with which they identify to a greater or lesser extent. The boundaries (in relation to social practices) between cultures can be described as ‘blurred’ and thus not clearly delineable or definable. Culture is thought of here primarily in terms of interpersonal relationships and conventionalized social interaction. This social practice includes everything that is considered normal, relevant, and plausible in a group of people. Culture as a set of social practices is evident within human collectives (lifeworlds). The concept of collectives includes all distinguishable groups, ranging from business enterprises to sports clubs to the nation-state. The open concept of culture captures the dynamics of change within cultures and understands culture as a process.

The members of a collective, despite sharing commonalities, are also characterised by difference (heterogeneity). Consequently, collectives cannot be conceived of as units (homogeneous and coherent). The simultaneous affiliations of a collective’s members are reflected in the diverse habitual repertoires and interpretive possibilities of the individuals within it.

In every interaction, according to our approach, whenever individuals interact, they are culturally influenced by the range of collectives to which they belong. Since individuals have numerous memberships and this fact is usually not a problem or not immediately noticeable, they seem to be able to deal with these partially contradictory memberships in everyday life. Accordingly, everyday interaction is characterized by the processing of difference. Difference is thus not a problem, but rather normality.

According to this approach, interculturality is understood to be the lack of awareness of the spectrums of difference (multi-collectivity) between interaction partners and focuses on the process that occurs between them. Rathje (2018) uses the missing link metaphor for interculturality in terms of the lack of awareness of the respective spectrums of difference. From this perspective, issues such as a lack of familiarity, a lack of a sense of belonging, and a lack of common habits emerge as new challenges.

Against this background, the difference between the challenges involved in general action competence and those encountered in intercultural action competence becomes evident, since the latter involves a heightened degree of uncertainty of action. Due to the lack of familiarity, the lack of a sense of belonging, and the lack of common habits, interaction is experienced as intercultural and the degree of uncertainty of action increases. However, the "missing link metaphor" also points out that unknown difference can become known difference. Even if individuals refer to different cultural experiences during the interaction process, new rules of normality and plausibility can be constructed in a negotiation process. The result is then not interculturality, but culturality. Through this negotiation process, interculturality and culturality become less easy to differentiate from one another.

Interculturality and culture production

Source: Based on Rathje, 2018, p. 9.

Illustration by Julia Flitta (https://www.julia-flitta.com), CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 license

Click on the image for a larger view

Interculturality is thus not an objective fact, but a context-dependent feeling (lack of familiarity, normality, routinised action, plausibility and meaningfulness). Interculturality can be transformed into normality through focussing on shared affiliation.

Accordingly, the success of intercultural interaction hinges upon the extent to which it is possible to create common contexts of action without crossing the acceptance boundaries of the participants involved.

Interculturality, then, is an experience of indeterminacy that inherently involves a subjective lack of relevance, plausibility and normality, which in turn means that routine actions are not possible. If we see intercultural competence as a transfer competence, then we are more likely to perceive this indeterminacy as a challenge (not a threat). In particular, if the concepts of unfamiliarity, uncertainty and multivalency are embraced as an inherent part of the process, then actors are more likely to open up to the unknown and might even experience it as something positive (nescience). Such a mindset also contributes to allowing diversity and ambiguity and thus a heightened level of flexibility. The challenge of togetherness consists in negotiating conditions for a common normality: Intercultural competence means acting relationally, reflexively and at the same time deciding appropriately how much definiteness (structure) is necessary and how much indeterminacy/opening (process dynamics) is possible in each individual context. In this way we can shape togetherness constructively and sustainably (Bolten, 2020). Due to its high degree of context dependency, we cannot, however, predict whether security or insecurity will be present in each situation. For this reason, it is difficult to determine where intercultural competence begins. Whether the afore-mentioned transfer competence is necessary only emerges in each individual context. Intercultural competence cannot therefore be described or measured in absolute terms.

According to this approach, interculturally competent persons can act competently in situations that do not seem normal at first (in the sense of Schütz/Luckmann's concept of lifeworlds) and are unfamiliar or not very familiar. When uncertainty arises in an unfamiliar context of action, intercultural competence is always required in the form of transfer competence. Intercultural competence thus paradoxically involves familiarity with the unfamiliar (ibid., p. 33).

Intercultural action and transfer competence

Source: Bolten, 2016a, p. 34. Graphic recreated by Vera Harder.

Click on the image for a larger view