1. Epistemology, learning theories and teaching and learning methods

The situations in which intercultural learning takes place are very wide-ranging. However, there are some commonalities. It always involves a learning process that is culturally shaped, and in which the learning culture must be considered. As a rule, the design of intercultural teaching and learning also depends on the teaching and learning culture that is present. This is because cultural shaping of teaching and learning influences the learning goals, the epistemic motivation, the teaching contents, didactic beliefs, and teaching/learning traditions. Before we look more closely at intercultural teaching and learning, we will first turn to the concept of learning, since assumptions about learning lead to corresponding theories of teaching and learning.

"What is learning?" is a question that is repeatedly posed and investigated in disciplines ranging from brain research to biology, psychology, and sociology. In the classical definition, learning refers to "the change in the behaviour or behavioural potential of an organism in a particular situation that results from repeated experiences of the organism in that situation" (Bower/Hildegard, 1983, p. 31; translated).

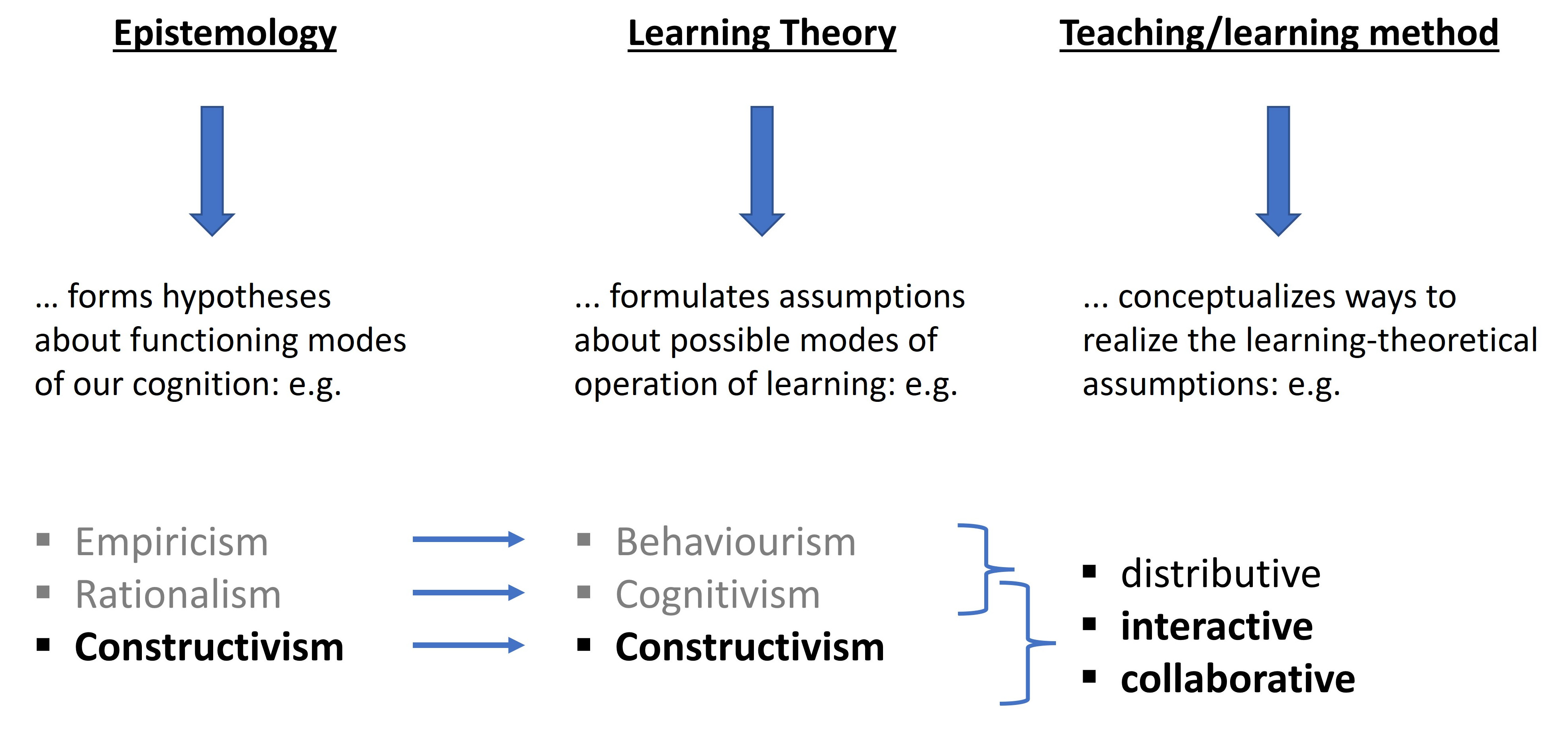

This definition contains three central elements: behaviour, cognitive learning processes and experience. These have been examined in partially in competence research and specifically research on intercultural competence. The conditions that must be fulfilled for the emergence of knowledge depends on the epistemology that is employed. The underlying assumptions of this manual are based on the epistemology of constructivism.

Epistemology and learning theory

Source: Adapted from Bolten, 2020.

The first epistemology in this figure is empiricism. Empiricism (Latin "empiricus", following experience) deals with the core question of the Enlightenment: Is there cognition without man first encountering the external world? Representatives of this philosophical tradition of thought include Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), John Lock (1632-1704), and David Hume (1711-1776). John Lock (1689) dedicates his major work, Treatise on the Human Mind, to empiricism. Empiricists reject knowledge independent of experience because they assume that the human mind is initially a tabula rasa. All insights can only be based on knowledge that we obtain from experience through the senses (seeing, hearing, tasting, smelling, touching). Statements about the world can only be made through real experience. Empiricists base their theses on empirical field and laboratory investigations in which objects, living beings or facts are observed. Their insights are derived from this knowledge about, for example, human behaviour, animal species or even the solar system.

Rationalism (Latin "ratio", reason), on the other hand, assumes that knowledge is possible from pure thought. Man is therefore not dependent on experience to have knowledge about the world and its logical structure. The sentence "I think, therefore I am" (René Descartes 1596-1650) highlights the human mind. The interest in knowledge about reality from the thinking I leads to the conclusion that we have an I-consciousness and are endowed with the ability to think. The rationalists assume that only the human mind can grasp reality. Accordingly, calculable regularities that follow logic, such as those found in mathematics or physics, are crucial.

The epistemology of constructivism (Latin "construere", to shape) is a collective term for different schools of thought of the 20th century that assume that people do not simply map the world with their perception, but first construct it. That is, constructivists assume that human knowledge does not correspond to objective reality. Consequently, man is not able to always perceive objective reality in an all-encompassing way. People construct their own subjective reality through -among other things- their active engagement with the environment.

The beliefs that stem from these epistemologies are reflected in assumptions about learning, i.e., in learning theories. There are many learning theories, the best known of which are behaviourism (learning through reinforcement), cognitivism (learning through insight and cognition), and constructivism (learning through personal encounters, experiencing, and interpretation). (See also th figure above).

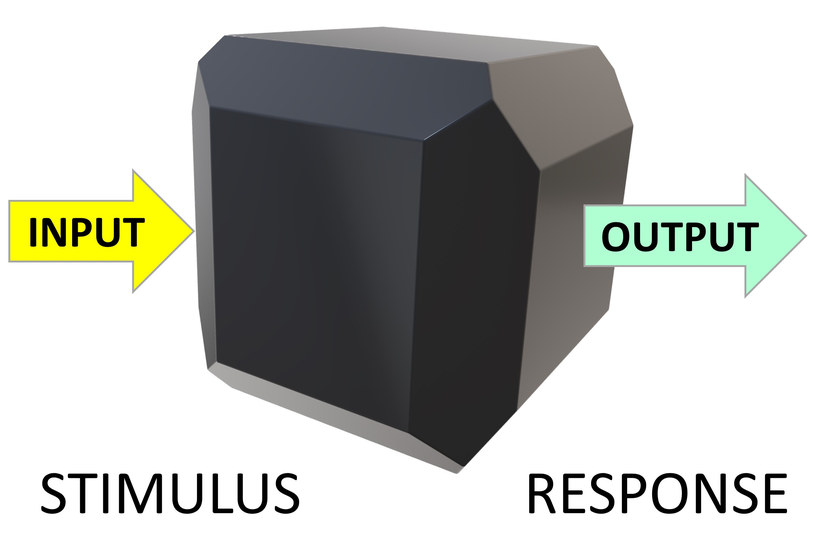

Behaviourism, with its main representatives I. P. Pavlov (1849-1936), J. B. Watson (1878-1958) and B. F. Skinner (1904-1990) is epistemologically based on English empiricism (John Lock 1632-1704). According to this, memory is tabula rasa onto which experiences are inscribed. One of the ways inscribing can occur is through conditioning via stimulus-response learning as shown in Figure 8. This means that a reaction is trained when presented with a certain stimulus (e.g., Pavlov's dog or Skinner's box).

The black box model of psychology

Source: Based on Bolten, 2020

This form of learning can be seen in language laboratories or also in learning programmes for foreign languages, in which sentences are spoken (stimulus) and are internalized through repetition (reaction). Learning is extrinsically motivated.

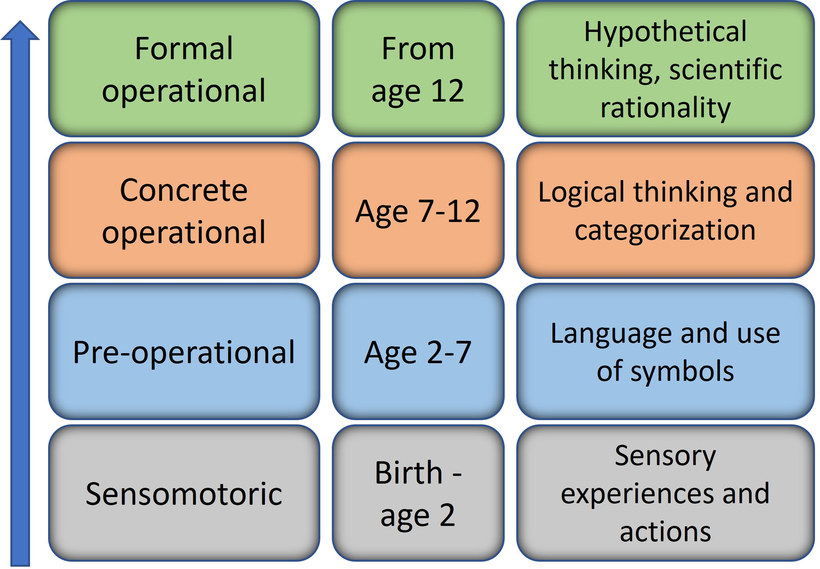

Cognitivism is epistemologically based on French rationalism (R. Descartes 1596-1650; C. Wolff 1679-1754). As a branch of psychology, cognitivism is primarily concerned with information processing and the higher cognitive functions of humans. In contrast to behaviourism, memory or consciousness is not a black box. Here, the focus of interest is on consciousness’ ability to formulate hypotheses about learning processes. One of the formative representatives of this kind of cognitive psychological approach was Jean Piaget (1896-1980). Learning takes place as a cognitive engagement with what is experienced. The learner actively engages with the environment (discovery learning), derives rules and reacts both autonomously and metacognitively (see the following figure).

Stages of cognitive development

Source: Adapted from Bolten, 2020

This means that the inner processes of people are the subject of research, i.e., the way people take in, process, understand, and remember information. Learning is intrinsically motivated (Bolten, 2020).

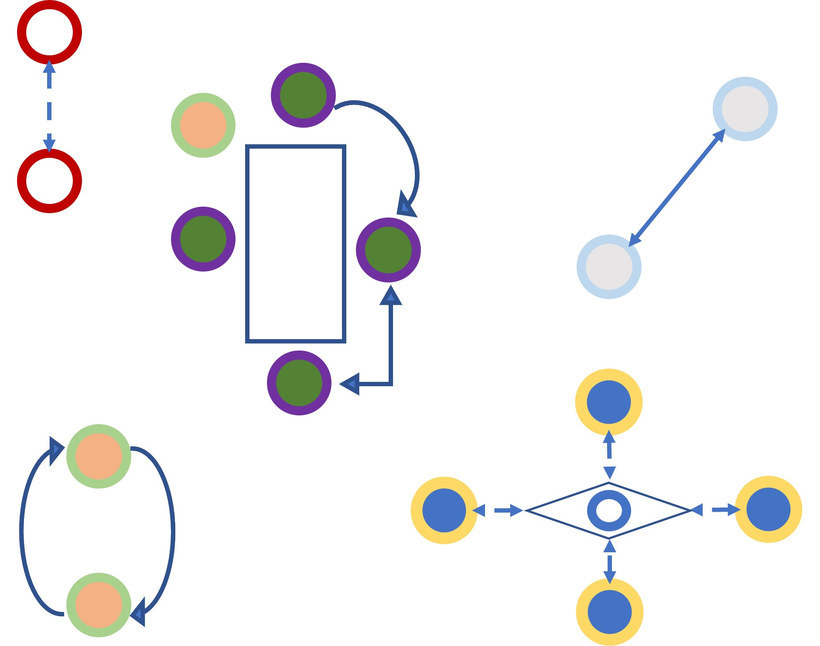

- takes place as an individual process of construction through collaborative networking in specific social environments,

- takes place as a process of sharing individual experiences as well as images of reality and cannot be predicted precisely,

- takes place without clear role assignments in the sense that teachers are also learners and vice versa.

Constructivist learning

Source: Adapted from Groshell, 2019

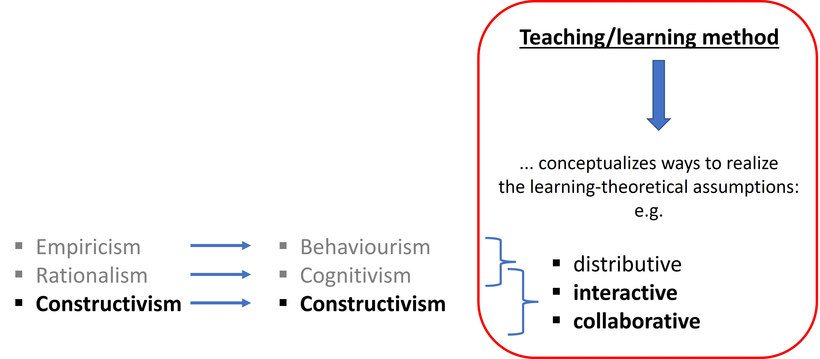

Learning theories derived from epistemologies lead to specific teaching and learning methods based on their respective assumptions about learning.

Teaching and learning methods are in effect the strategies that people have developed in order to realise particular epistemological interests, objectives and learning theory beliefs in a particular context. That is, teaching and learning methods are guided by the hypothesis of the particular beliefs about how knowledge is generated and transmitted. Accordingly, teaching methods are based on knowledge (hypotheses) about learning processes. They are developed from learning theories, as seen in the following figure.

Teaching and learning methods

Source: Based on Bolten, 2020

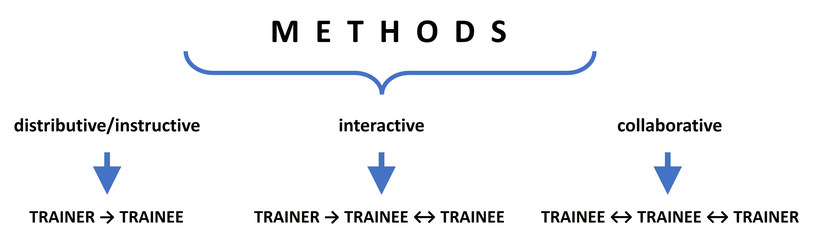

- From empiricism emerges behaviourism and so it follows that teaching and learning methods designed to realize this objective are instructive/distributive.

- From rationalism emerges cognitivism and therefore teaching and learning methods are instructive/distributive and interactive.

- Constructivism follows constructivist learning theories, resulting in interactive/collaborative teaching and learning methods.

To gain a better understanding of the different teaching and learning methods, watch the following video:

Video: Comparison of teaching and learning methods

Source: Theories of learning: behaviorism, cognitivism, & constructivism, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HulIkh7BYt0

This video was produced Annalyn Bagasbas. It illustrates the connection between epistemology, learning theory and learning methods.

The criteria for deciding which epistemology, learning theory and methods are chosen for intercultural teaching and learning depend on what we understood by intercultural competence. Based on the previous description of our understanding intercultural competence, we can formulate the following criteria for the design of teaching and learning processes:

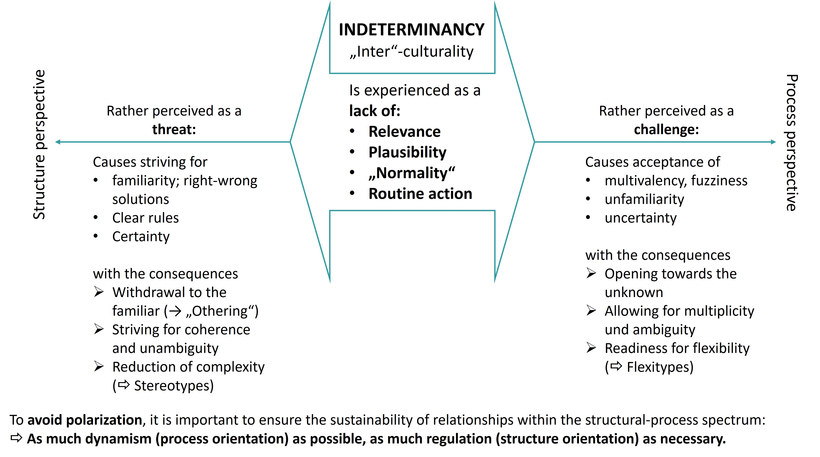

- Interculturality as an experience of indeterminacy means a subjective lack of relevance, plausibility, and normality, which in turn means that routinised action is not possible.

- If intercultural competence is our goal, then Intercultural learning as a component of the learning process can contribute to perceiving this indeterminacy as a challenge or even as an opportunity (not as a threat). The challenge when building togetherness lies in negotiating the conditions for a mutual normality.

- In this situation, intercultural competence means acting in a relationally reflective manner. Further, it requires the ability to decide, in a context-appropriate manner, how much determinacy (pertaining to structure) is necessary for those involved in a specific context of action and how much indeterminacy/opening (pertaining to process dynamics) is possible, in order to be able to shape togetherness constructively and sustainably.

- This succeeds in particular through acceptance of multivalence, unfamiliarity and uncertainty. The goal here is that people open up to the unknown, which in turn contributes to an allowance of diversity and ambiguity (willingness to be flexible) (Bolten, 2020).

Designing intercultural teaching and learning in such a way that views the foundations of intercultural competence as a transfer competence inevitably leads to constructivist epistemology and learning theory. In order to gain a better understanding of this inference, we would like to invite you to deepen your knowledge of constructivism in the following.

2. Assumptions about intercultural learning from a constructivist perspective

If we answer Paul Watzlawick's question "How real is reality?" from a constructivist point of view, the answer would be "Reality is only as real as it is for humans". This might seem confusing at first glance, but it underlines the basic constructivist assumption that reality is dependent on observation and is therefore purely subjective.

Constructivism takes place in a lifeworld, i.e., in a social environment. For this reason, it is always social constructivism (Siebert, 2005, p. 17; Reich, 1998, p. 385). The concept of the lifeworld used here goes back to Alfred Schütz. The everyday lifeworld is the reality "in which people participate in avoidable, regular recurrence" (Schütz & Luckmann, 1979, p. 25; translated). We can intervene in this lifeworld and change it; at the same time, events, actions and consequences to our actions exist in the lifeworld that limit our freedom of action. The lifeworld is shared intersubjectively. It is characterized by meaningfulness and plausibility. As a result, it is experienced by people as normal and not questioned (Schütz/Luckmann, 2003, p. 49f.). This enables people to act through routines. Reality is not only constructed through symbolic interactions with social reference groups, but also through political and economic relationships that are characterized by power, hierarchies, participatory inclusion/exclusion, property, mass media etc.

Constructivist assumptions about how reality is constructed correspond to our understanding of culture and indeed the resultant definition of culturality. This approach is also reflected in Rathje and in Bolten's approach to intercultural competence and their concept of it as a transfer competence.

Communication is our access to an intersubjectively shared reality. It is the human practice that simultaneously establishes identity, relationship, society, and reality, and is also the means by which people intentionally send messages to one another. In this understanding, communication primarily serves to convey social identity and social order (Keller, Knoblauch & Reichertz, 2013, p. 13). Communication is the medium of our social construction of reality (Yildirim-Krannig, 2014, p. 205). Accordingly, communication enables the coordination of interpersonal actions and also social belonging. Since communication is based on language, the structure of communication is always culturally predetermined. Language is the most important medium in our creation of reality (Siebert, 2005, p. 56). Our mother tongue, but also subcultural milieu languages, professional languages and dialects are the expression of and a prerequisite for our construction of reality (Siebert, 2005., p. 24; Kriegel-Schmidt, 2011, p. 138). Language does not depict the outside world realistically, but rather interprets reality and creates reality of its own kind (Siebert, 2005, p. 56). Herbert Blumer's symbolic interactionism (1969) refers to this, based on Georg H. Mead's reflections on the development of identity (Geist, Identity and Society, 1934).

What implications can be derived from the approaches of constructivism, presented above, for teaching and learning contexts?

From a constructivist perspective, learning emphasizes individual construction processes:

- The learning process is dependent on one's own previous experiences, individual perceptions, and interpretation processes. The stocks of knowledge generated during learning cannot therefore be understood as an objective image of the world but are subjective constructions (Mietzel 2019; quoted from Gudjons/Traub, 2020, p. 236).

- In constructivism, learning is always understood as an active process in dealing with other subjects in the sense of social constructivism.

- Learning and construction processes work most effectively in exchange with others. This approach to learning strives for a common understanding by verbalizing and comparing individual constructs (cf. Gudjons/Traub, 2020, p. 236).

- Learning as a construction of reality is a lifelong process.

Whether and what is learned depends less on the inputs and more on the individual cognitive-emotional pre-structure and the psycho-physical state of mind, but also on the context, i.e., on the learning environment, the learning group, the biographical and professional usage situations. Learning is not a transporting of knowledge from A to B. Meanings cannot be communicated in a linear manner, but the system constructs its own world of meaning (Arnold, 2015, p. 32).

Ideally, learning expands the range of possibilities for reality construction and thus people’s repertoires of actions and problem solving. Constructivist learning requires opening up to the new, to the foreign, to the confusing (ibid., p. 34).

Constructivist learning theory opens up didactic possibilities when we consider the way people construct their reality:

- Construction: "We are inventors of our own reality.", i.e., we construct new images and experiences, for example through experiments.

- Reconstruction: "We are discoverers of our reality.", i.e., we discover the realities of others and integrate them into our own experiences.

- Deconstruction: "Things could also be different! We are the unmaskers of our reality." This is a perspective that questions certainties in favour of critical or sceptical objections. As an observer, we can in this way adopt a completely different point of view (Reich, 2010, p. 118 ff.; Reich, 2012, p. 182 ff.; Holtz, 2008, p. 107 ff.).

3. Intercultural teaching and learning against the background of constructivist didactics

From a constructivist perspective, didactics refers to all areas that relate to the construction of and changes to perceptions, while enabling us to plan and design learning situations (Arnold, Krämer-Stürzl & Siebert 2011, p. 78). Didactics must always consider the following question:

Who (learning facilitator) enables whom (learners), through what (content), for what (goals), how (method), with what (media), when and where (learning environment), to which result (effect)?

From a research point of view, the didactics of teaching always concerns constructions of reality that are of a mediating nature. Didactics mediates between the communication partners involved (two people, several people) according to certain patterns. This is the central starting point for constructivist didactics.

When selecting intercultural teaching and learning methods, the teaching and learning context, the learning objective, the target group, and the content all need to be taken into account.

Reciprocal interdependent relationships between factors

Source: Based on Bolten, 2011, p. 3

Didactic objectives can be achieved by using certain methodical tools (the methods). How these tools are formed essentially depends on the level of expectation that is associated with learning processes. These theoretical premises on learning also try to do justice to the cognitive interest of a target group. Or the other way around:

Recognizing what is important for us in order to be able to orientate ourselves in our living environment and master the demands on us to act appropriately, directly structures the type of learning that is most suitable for us in this context.

Therefore, the specific way that we learn something (and of course teach) influences in turn the conceptualization and choice of methods that we use to achieve this. This subsequently determines the suitability of certain exercise methods and teaching practices (Bolten 2011, p. 4).

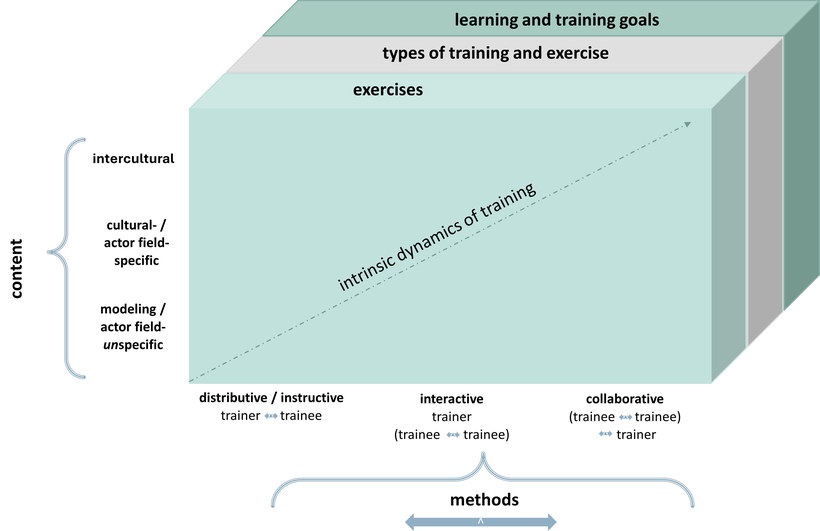

We will now take a closer look at these methods of intercultural teaching and learning. With his methods map, Bolten (2011) illustrates which methods, contents, exercise types and exercises are suitable for specific target groups and learning scenarios in connection with specific learning objectives. His model is designed for the conception of intercultural training but can be transferred just as well to other intercultural teaching and learning contexts.

The method map

Source: Bolten, 2016b, p. 85. Graphic recreated by Vera Harder.

Click on the image for a larger view

On the Y-axis are the various forms of teaching and learning content, while along the X-axis we can see the methods that we have learned in connection with epistemology and learning theories (distributive/instructional, interactive, collaborative). In addition, the model depicts the layers Exercises, Types of training and exercises and Learning/training goals along both axes. Below the method map we can see in which direction the methods are heading, depending on the method chosen: Distributive methods are more trainer/teacher-centred than, for example, interactive or collaborative methods, and so forth.

If we turn to the layer learning/training goals: The objective of intercultural teaching and learning essentially determines the content of seminars, training courses, workshops, etc. Common categories here are a) culture-unspecific, b) culture-specific and c) interculturally oriented content. This manual focuses on culture-unspecific content, as this corresponds to the objective of the Intercultural Communication course.

The teaching of culture-unspecific content

1st example: Objectives for culture-unspecific content

Understanding of perception processes, attributions, formation of stereotypes, how situations of indeterminacy arise and possible courses of action; knowing concepts of diversity and relationality, understanding the culture-constructive role of communication, understanding how trust is created, etc.

Appropriate method: Distributive/instructional

The content can be conveyed via models and theories on the respective topics, which are then conveyed in the form of texts, short presentations or educasts, for example. For practice purposes and to ensure understanding, explanatory films can be linked to target group-specific tasks.

Culture-unspecific content with distributive/instructional tasks to ensure understanding

With the help of a cultural model, the participants got to know the various understandings of culture and the resulting intercultural approaches. Subsequently, in order to reinforce this understanding, a task was introduced:

Task: Definition of the term "intercultural interaction"

Read through the definitions of interculturality and answer the following question: What do the definitions have in common and how do they differ? Record your answers in your learning journal.

Sort the definitions according to their position on a scale between an extended-open and extended-closed understanding of culture.

2nd example: Objectives for culture-unspecific content

To be able to deal with uncertainty/implausibility; to act in a way that considers multiple perspectives and communicating in a language-sensitive manner; To try out diversity and multiplicity concepts as well as holistic thinking and action models; training empathy in everyday practice, etc.

Structure-process perspective in relation to uncertainty

Source: Based on Bolten, 2020

Click on the image for a larger view

Appropriate method: interactive

Action-oriented exercises, multivalent role-playing games (role diversity of individuals), world café, simulations without culture-specific references, in which primarily experiences of insecurity/implausibility are generated; small group workshops etc.

Culture-unspecific content, interactive task

The goal here is the development of reciprocity, sensitivity, empathy, and strategies for action in unfamiliar situations (transfer competence) – with as much process as possible, and as little structure as necessary (see also Fig. 14). The focus is on the process, or the way participants design their relationships and not on the actors themselves. Rules are handed to the participants. Heterogeneous situations arise with an open-ended outcome.

BARNGA gameplay: The participants are divided into at least three groups. Each group receives a deck of cards and their own instructions with their own rules, which the others are not aware of. After everyone has familiarised themselves with the rules, no more talking is allowed, and the game can begin. After the third round within each group, the people who have won the most rounds leave their own group and switch clockwise to another group, so that at least one new member joins the group. The participants notice that their routine no longer works and suddenly there are completely different, supposedly unclear or illogical rules that they do not understand.

3rd example: Objectives for culture-unspecific content

To be able to deal constructively with uncertainty/implausibility through one's own initiative; To carry out projects involving culture-unspecific topics collaboratively and independently; To be able to develop group rules in order to negotiate plans of action in seemingly implausible, uncertain and/or complex situations.

Appropriate method: collaborative

Experiential education is based on experience-based learning. Borderline situations can mean that familiar patterns of action are disturbed so much that they no longer work. In this case, participants need to explore through trial and error, make adjustments in their perspective, and undergo a process of reorientation. Challenges should be overcome together. Learning is a natural social act and occurs through talking, trying to solve problems and trying to understand the world.

Culture-unspecific, collaborative task

- Within an organisation (e.g. a company), several teams are brought together and faced with a problem that needs to be solved. The problem in this case is the introduction of a new training programme. The task only gives a rough outline of what outcome is expected. The teams should then work on a solution. At the end, the teams present what they have developed, justify their choices, and outline their plans for completing the task.

- Ask students to create wikis, educasts, etc. on relevant issues in a subject area.

Teaching of culture-unspecific content

- The use of role-playing games or simulations is made more realistically complex through the use of multivalent actor scenarios. This reduces the risk of stereotyping, which can happen in culture A vs. culture B role-playing games

- Experiences of indeterminacy/ambiguity are part of creativity processes and should be considered when creating exercises.

- The inclusion of experiential educational experiences is recommended for the development of collaborative exercises

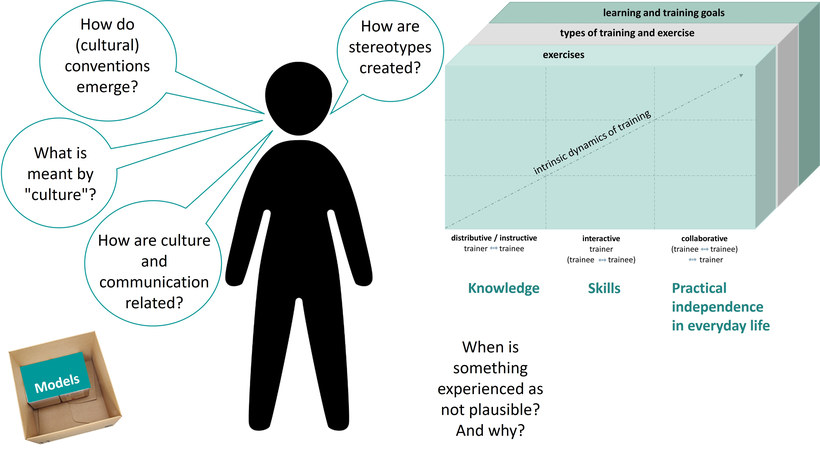

Summary: Teaching of culture-unspecific content

Source: Based on Bolten, 2020

Click on the image for a larger view

Culture-unspecific content can be taught using distributive, interactive and collaborative methods. The content to be conveyed determines the choice of method (Bolten, 2020).

The constructivist insight that learning material cannot be simply and easily transferred, places the learner at the heart of the learning process. Any attempt to transplant the highly networked relationships that are inherent in the subject matter is doomed to failure due to the wholly different backgrounds of the teacher and students in terms of previous knowledge, learning experience and socialization. If we assume that learners learn in a self-referential and self-organized manner, then it is evident that teaching and its didactics should be geared towards enabling precisely these learning processes.

Despite this, instructive/distributive teaching and learning phases are without doubt necessary to enable the development of cognitive structures in the declarative area of knowledge. They are, however, insufficient to move from knowledge to ability and to embed this in life and/or professional situations. Therefore, a learning schedule should always integrate phases in which an exchange occurs among learners (peers), and between learners and teachers, as well as phases involving goal-driven team processes. These activities would fulfil social-interactionist requirements in relation to constructivist teaching and learning. As social beings primarily, humans learn more deeply through language (communication), through explanation and mutual support in the learning process (interactive). People only experiences themselves when confronted with society or in exchange with others and this determines and develops their world socially. This kind of experiential learning is encouraged and supported in particular through collaborative methods.

Trainer/trainee learning orientation

Click on the image for a larger view

Achieving the teaching and learning goal of intercultural competence in terms of a transfer competence is possible through a combination of methods to stimulate holistic learning (cognitive, affective and conative learning goals), but remains a lifelong learning process.