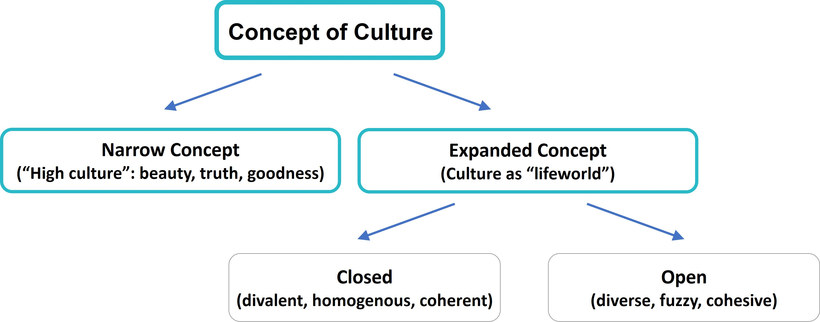

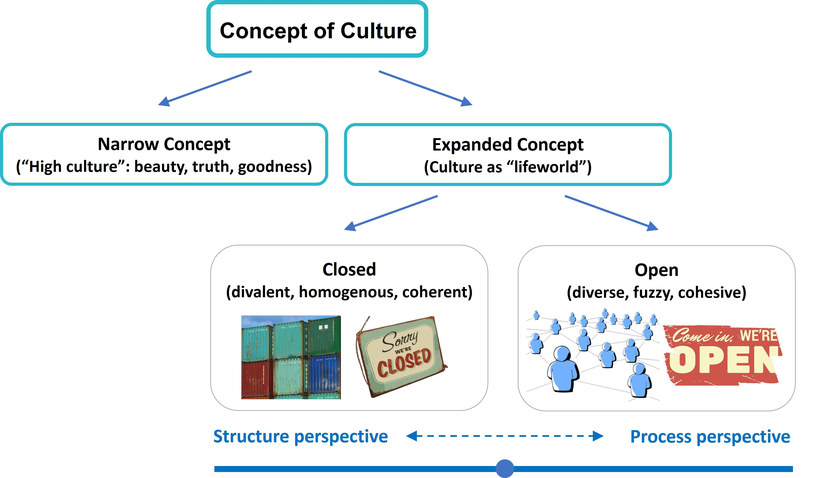

Considering cultures as living environments or lifeworlds means that culture is part of the individual's reality and their environment. Here the lifeworld is seen as the result of the actions of the human beings. Culture as a lifeworld has developed two different variants: the closed conception of culture and the open conception of culture. The closed view of culture embodies the idea that one group of people all possess the same or very similar characteristics and therefore can be clearly defined with sharp boundaries. In contrast, the open view of culture represents a movement away from conceiving cultures as stable and homogenous containers.

However, conceiving of cultures as closed or as containers means leads to considerable contradictions. This can be seen where an attempt is made to clearly define what belongs to a culture and what does not, in the sense of bivalent logic (e.g. 'right/wrong'; 'either/or'). A very typical example of such a thinking would be for example talking about Germans as coffee drinkers and the British as having their tea at five o’clock.

Nevertheless, from a pragmatic point of view, a concept of culture that is closed in this sense may have some advantages since it reduces complexity and, with its typifying simplifications, it enables us to gain an initial orientation with regard to cultural living environments of all kinds. Demarcations, however, are problematic due to migration movements and communication processes that have lasted for thousands of years, and “no living environment is conceivable as a homogeneous culture unaffected by external influences” (Said, 1996).

Task: Switzerland from a closed culture perspective

Switzerland, a comparatively small landlocked country in Europe, is commonly viewed as a country where people speak Swiss German. However, it is bordered by five countries, including Italy to the south and France to the west, with four recognised national languages: German, French, Italian, and Romansh. Furthermore, a distinction can be made between people who speak Swiss German and standard German. Almost two thirds of the population speak more than one language regularly. ("Switzerland", 2021)

If you were only to consider the basic information given here, where might you find indications that a closed concept of culture often does not help us to get to know the people of Switzerland? Note down your answers in your learning journal.

Having completed this task, click on the following link to view a possible answer.

Show / hide sample answer

Nations were created through historical processes, such as wars or treaties, and because of this at times people within national boundaries not only share a common government but also a history, a language, common experiences as well as values and norms. Japan is traditionally seen as an example of a nation state displaying a homogenous population group in that sense. However, in many cases, people living within national borders are heterogeneous and in the case of Switzerland, for examples, this relates to languages as well. The fact that so many different languages are spoken in Switzerland suggests that the people may also be diverse on other levels, making it difficult to apply a closed concept of culture to its inhabitants. This should alert us to the importance of being open to cultural differences and avoid making generalisations and assumptions about people. For example, in the case presented, thinking that learning Swiss German will be sufficient to communicate well with the Swiss may actually be a fallacy.

Increasingly, since the mid-1990s or even earlier, an increasing number of arguments have been proposed that reject container thinking. The predominant focus of the criticism has been the idea that culture is synonymous with the nation-state, a type of thinking which is still dominant among the closed variants of the expanded concept of culture. Against the backdrop of globalization processes, however, notions of homogeneity, i.e. that a group of people basically share the same characteristics, are proving to be increasingly untenable since nation-state cultural constructions tempt us into making unrealistic generalizations that encourage stereotypes, as the following example from an intern’s report suggests:

At the office, I asked my supervisor a question, offering two possible solutions (‘Do you think…or should we rather…?’). I wanted to find out which of the two options she preferred. Sadly, she started to reply after the first part of my inquiry and then became furious because I had not waited for her to finish her answer before asking the next question. She argued that it must be because I come from South America that I am not able to wait before immediately asking the next question, thereby confusing the speaker. It may have slipped her mind that I did not grow up in South America.

In the open perspective´s conception of culture, the lifeworld is seen as an open system. It is much more process and knowledge oriented, based on the understanding that culture is dynamic. It is a set of (constantly changing) practices through which social reality is created. Such a process view of culture is linked to an understanding of culture as knowledge. Through learning, individuals acquire knowledge about the way things are done and thereby gradually gain a sense of familiarity. This process leads to cultural cohesion, which means that culture is the glue that connects people. The basis of this is common knowledge and shared meaning.

This understanding of culture has the advantage that it captures the changes within cultures and their dynamics. Thus, culture is diverse, fuzzy, heterogeneous and cohesive. Bolten (2015) describes this perspective as an either/or AND both/and perspective. From this viewpoint, the construction of something that is our own and something that is foreign is no longer tenable. Since the lifeworld is our familiar world, it provides sense and meaningfulness for everyday actions. For the individual, something is meaningful if it is characterized by relevance, plausibility, normality, thus enabling routines (Schütz & Luckmann, 1979, p. 30).

The open view of culture represents a multi-relational type of thinking. According to this, not only national cultures are relevant, but also a range of other cultures, such as profession, age, gender, social or educational status, club affiliation and family among others (Hansen, 2009), all of which influence our values (what is seen as good, bad, to be strived for, to be avoided), behaviour and patterns of thinking. This new open conceptualisation of culture allows for the fact that each person possesses not only multiple affiliations with many different cultures, but also that they might identify with these cultures to a greater or lesser extent. The boundaries from one culture to another are therefore not sharply definable and could be said to be fuzzy (Bolten, 2015). Viewed in this way, the influence of culture on a person’s lifeworld is therefore the ever-changing influence of an intricate and unique mix of the cultures to which they have been exposed or decide to belong.

The following graphic illustrates the narrow and the expanded concept of culture as well as the closed and the open view of culture:

Source: Bolten, Jürgen (2015, p. 46), adapted and translated

Case "Beibei from East Frisia"

Beibei is a freshman at the university and joins an online get-together with lectures and fellow students. She introduces herself to one of the lecturers who comments: ‘Nice to meet you, where do you come from?’ Beibei answers: ‘From Leer’ which is a city in the far north of Germany and which prompts the lecturer to ask: ‘But where do you really come from?’. ‘From East Frisia’ is her reply indicating the region in the north of Germany. And in fact, this is the region where Beibei was born.

Use the closed and open concept of culture to explain the confusion and misunderstanding above. In doing so consider: What are the indications that suggest the lecturer based his question on a closed 'container' type thinking and conception of culture? Please note down your answers in your learning journal.

Having completed this task, click on the following link to view a possible answer.

Show / hide sample answer

The reaction of the lecturer leads us to believe that he had a closed concept of culture in mind when posing the question "Where do you really come from?". When Beibei replied that she was from Leer, it is likely that Beibei's name and appearance did not fit his perception of "people from East Frisia", or any other region within Germany. Thus, he probably looked for an alternative explanation that would fit Beibei into a category such as China, for example. By asking Beibei where "she really came from" he indicated that he expected Beibei to feel another affiliation to a region that would fit her appearance and name, at least from the closed culture perspective of the lecturer. Beibei, however, may or may not feel affiliated to a country or region other than East Frisia or Germany.

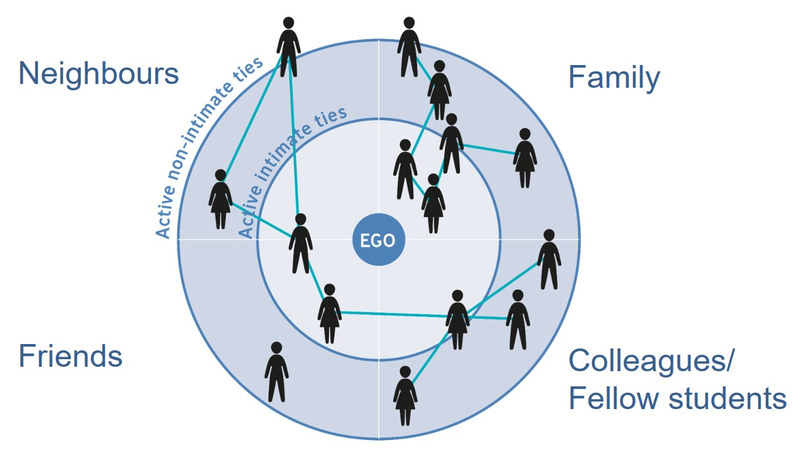

The fact that there are quite different answers to the question of a person's origin, depending on their point of view, or that someone might have very different roles, makes it difficult to classify them definitively. A non-sharp definition of cultural affiliations therefore corresponds far better to reality: One might have a certain profession but at the same time be involved in numerous other roles and collectives, either within the family or through friendships, leisure or virtual relationships. This type of understanding of multi-collectivity was described by Hansen (2009) and is analogue to Bolten’s notion of multi-relational networks focusing on the relationships between actors (Bolten, 2011).

Along with the individual, this multi-relational concept of culture also affects groups, organizations, and societies in a much more pronounced form, regardless of which cultural actors are involved. Cultures are therefore not conceivable as sharply delimited fields of actors, but should rather be conceived of in terms of their links with other cultures and collectives. As mentioned above, the boundaries are blurred or fuzzy (Bolten, 2015) and should rather be considered as a network.

The following figure shows the networks EGO is a member of by considering four collectives. It shows the linkages and ties between EGO and the people in his/her network but also the relationships between the members. For example, some of the people in the network may be friends as well as fellow students. It also differentiates EGO’s relationships as actively intimate and non-intimate at the time when the image was drawn, showing that not only connections are important, but also the quality of those connections, and that these relationships change over time. For example, through working closely together in a team, a colleague who used to be an acquaintance, may become more of a friend.

Source: Based on Chua, Vincent, Julia Madej & Barry Wellman (2011, p. 102). Personal communities: the world according to me. In: John Scott and Peter J. Carrington (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Social Network Analysis. London: Sage Publications, pp. 101-115.

Figure by Julia Flitta (www.julia-flitta.com)

If we view culture in the context of today’s globalization processes, then we can clearly observe that economic, technological and political as well as professional and personal networks have established themselves across national borders. This emphasises the understanding of cultures as open systems and open networks of cohesively connected collectives (Bolten, 2014; Hansen, 2009; Rathje, 2009), rather than coherent constructions of homogeneity.

Task: Find your own example

Understanding culture from an ‘either/or’ AND ‘both/and’ perspective, as the open concept suggests, allows us to consider Beibei’s sense of belonging from a multi-collective and multi-relational perspective. She identifies Leer as her home town and feels attached to it. Her name suggests that she or her family also feels attached to other collectives, which may or may not be China. If this is the case, the answer to the question ‘Where do you come from?’ could be ‘either/or’ AND both/and’, depending on self-ascription. In our case she obviously considered her answer to be the most relevant in the specific context.

Think about an example where an 'either/or' AND 'both/and' perspective could have supported a more differentiated view and note this down in your learning journal.

Having completed this task, click on the following link to view a possible answer.

Show / hide sample answer

As an example, take this dialogue between Ian and Gavin from the UK. They chat while waiting for a meeting to start.

Ian:

I am working with this colleague from Bangladesh, Kashif. It’s interesting, but sometimes challenging. It looks like they have a very different understanding of deadlines! It can be frustrating to constantly remind him of the deadlines we agreed on. I know that India and Bangladesh are two different countries, but I visited an intercultural training seminar some time ago, where they explained to us that the attitude towards deadlines is just more relaxed than it is here. That helps me a bit to see that he doesn’t mean it personally at least.

Gavin:

Well, you are right, it is possible that what you observe with Kashif can be explained that way. Have you considered though, that not only is India different from Bangladesh, but that there might also be a big difference between people within these countries? I remember you told me Kashif is new to our company. This might also be influencing his behaviour. We also do not know if he is from the countryside or the city, what his age is, or his general personality. It is even possible that his parents are from the UK, and he himself feels very British. So honestly, I would be a little sceptical with absolute statements from these intercultural workshops, especially when they claim that people from a certain national background necessarily share particular traits. If I were you, I would just take some time to talk to Kashif on an informal level, and see if you can get to know him better, to see what makes him "tick" as a person.

In summary, we view culture as an open, ever-changing system, emphasising its knowledge-based and processual nature. This process aspect of culture leads to cultural cohesion, and thus culture can be seen as the glue that connects people, the basis of which is common knowledge and shared meaning. This understanding of culture is depicted below, and includes the structural as well as the process perspective.

Source: Bolten, Jürgen (2015, p. 46), adapted and translated.

Images by Pixabay. Accessed 15 May 2021. Pixabay License

Using an expanded and open definition of culture requires us to look closer at individuals and their membership of different groups or collectives, thus taking a micro-perspective. If we want to establish a trusting relationship with virtual team members, such a micro-perspective is important in order to gain the necessary in-depth knowledge of the people in our new collective, or team. An in-depth view based on an open definition of culture allows us to take on the aforementioned either/or AND both/and perspective, which enables us to see commonalities as well as differences. With such a perspective, our construction of what belongs to us (‘our own’) and what does not (the ‘foreign’) is no longer tenable and the transition from the ‘unfamiliar other’ to the ‘familiar other’ is gradual and contextual. It helps with the understanding that ‘they are us’. An expanded and open understanding of culture therefore enables opportunities for inclusion and an open, network perspective as the illustration below indicates.

An open concept of culture lays the groundwork for inclusion in the sense that it supports the process of all involved parties becoming part of the collective. In the context of virtual teams this would encourage an awareness of how important it is to establish a collective in such a way that every member feels part of it. The open network perspective takes this a step further by indicating that team members are also members of other collectives. Through these multiple team member affiliations the team can access information that would otherwise have been obscured to them and thus team performance can be considerably enhanced.

We have now seen that cultures are dynamic, ever-changing networks without sharply definable borders. We have also observed that each individual has multiple memberships of a range of cultures. These influences are either consciously or subconsciously combined in order to make up a person’s individual lifeworld.

If this is so, then the question logically arises: ‘If cultural memberships are multiple and the borders between cultures are fuzzy, then how can we make sense of cultures or even describe them at all?’ In order to answer this question, we will take a short digression into the world of “Zooming”!

When we view cultures, we are always taking on a particular degree of abstraction. The process of zooming helps to illustrate this. The closer we zoom in to the actor contexts and focus on the details of the micro-perspective, the more questionable initial macro-perspective constructions of homogeneity appear. This means that zooming helps us to see both structure and process. This also means that rather than seeing zooming-in and zooming-out as two viewpoints and therefore as an ‘either-or’ binary choice, it is more helpful to view them as being located on a gradual continuum stretching from “structure” at one end to “process” at the other. Viewed in this way we have a realistic way of conceiving of culture, and can accept that all points along the continuum might be relevant in particular circumstances and with particular objectives in mind. Culture is therefore both structure and process (this is the “both/and” approach).

Photograph by Adelheid Iken

As we see in the photographs, the image will change depending on how far we ‘zoom out’ and how far we ‘zoom in’. This inevitably creates a paradox, since hardly anyone will deny that despite the obvious heterogeneity of individual actors, there are certain situations in which it can be legitimate and meaningful to talk about ‘German’ or ‘Chinese’ ways of thinking and acting. In other words, what turns out to be heterogeneous from a microcosmic point of view, may well seem homogeneous from a macrocosmic (or 'outside') perspective.

To put it another way: Culture is both heterogeneous and non-heterogeneous (Hansen, 2009, p. 121; Moosmüller, 2009, p. 56). In this case, the idea would be: Both the either-or type of thinking that embraces cultural homogeneity as well as the both/and thinking that embodies a fuzzy understanding of culture are simultaneously equally valid. Accordingly, fuzzy not only relates to the concept of culture itself as a network of relationships, but also to the nature of the perspective that is used when viewing culture: This degree of ‘fuzziness’ determines how homogeneous/ heterogeneous we understand a culture to be (Appadurai, 1996, p. 31). In other words, both binary and fuzzy views are justified under particular conditions and in specific contexts.

In sum, when we view culture holistically and on a structure-process continuum, zooming is a tool we can use in order to change perspective, depending on the context and objective that is relevant at any given time.

Task: 'Zooming' – a new perspective on culture

Watch the YouTube video on 'Zooming – A new perspective on culture' and carry out the following tasks.

- What is zooming?

- What is meant by zooming out as much as necessary and zooming in as much as possible?

- How might zooming in on a virtual team support or hinder the development of a productive team culture?

- Why is zooming an important concept in order to get to know virtual team members? How can zooming help to consider different perspectives?

Having completed this task, click on the following link to view a possible answer.

Show / hide sample answer

1. What is zooming?

The concept of zooming in and out of cultural collectives is the technique of looking at something either very closely or from a distance. The technique thus involves looking at something from different angles.

2. What is meant by zooming out as much as necessary and zooming in as much as possible?

Zooming in as much as possible refers to the understanding that we need to capture as many details as possible in a particular context. Zooming out as much as necessary means that we should be cautious not to generalize too much, but can gain some insights from a wider view of the collectives involved.

3. How might zooming in on a virtual team support or hinder the development of a productive team culture?

When we zoom in too much, the diversity of behaviour, goals and values within the team can be overwhelming, making it challenging to achieve consensus. However, when we zoom out too much, we might perceive common ground which in reality does not take into account the real interests and needs of the people we work with. It is therefore important to achieve a balance of focus in order to do justice to both, team members' individual characteristics and needs as well as considering the cultures and collectives involved.

4. Why is zooming an important concept in order to get to know virtual team members? How can zooming help to consider different perspectives?

Zooming out enables us to initially put the team into rough categories. This step allows us to grasp the general level of diversity in the team, which can help us to be more aware of the team members' different perspectives. However, in order to really get to know your team, it is important to also question these categories, and make an effort to see the individual traits of team members by zooming in.