The video 'Zooming' indicates the importance of the concept when encountering others and working in virtual teams. A key message from the video is that the characteristics and perceived homogeneity of, for example a group of people, change when the viewpoint changes. This should encourage us to question our homogeneity assumptions when meeting new team members. With this in mind, and considering the open concept of culture, the next step is to explore interculturality.

As we saw in the previous section, concepts of culture have moved from the idea of cultures as static, homogenous, nation-bound units or containers (e.g. studies from E.T.Hall 'Beyond Culture' and Geert Hofstede "Culture's Consequences') to conceptions that embrace a more fluid, dynamic and multi-relational notion of culture.

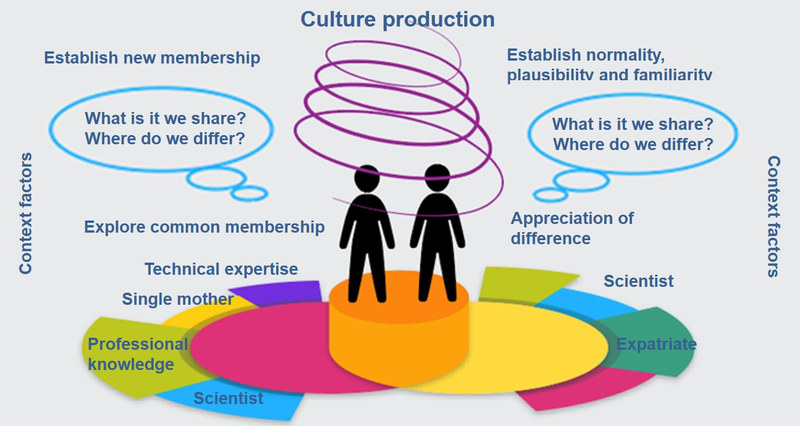

From a practical point of view this means that we understand team members to have relationships with a range of people and to be members of a range of different collectives. Additionally, the figure below indicates that some of the collectives with which a team member feels associated have a stronger influence on him/her than others. For example the turquoise area may show an affiliation to their profession, which is considered to be highly relevant in the context of an upcoming team project.

Source: Based on Rathje, Stefanie (2015). Multicollectivity – It changes everything. Key Note Speech at the SIETAR Europe Congress (SIETAR_slides_Rathje.pptx (stefanie-rathje.de)). Accessed 24 May 2021.

Figure by Julia Flitta (www.julia-flitta.com)

Imagine that a team member shares membership of a professional collective with another team member. In this case their relationship is characterised by culturality. At the same time they may diverge in their membership of other collectives, which nonetheless play an important role in their interactions. In this case their relationship can be characterised by interculturality. Thus the relationship between two and more actors can be characterized by both interculturality and culturality (Auernheimer, 2010, p. 60).

The figure below illustrates this with the example of two protagonists A and B: They are predominantly socialized in different contexts and thus diverge in their membership of a number of collectives, while sharing some others. This is the basis for them to explore differences and commonalities. They share membership of the gender collective and thus they are likely to find topics to discuss and observe here. However, because person A spent many years working abroad and person B did not, they are less likely to find common ground with many of the issues that stem from international experience. This will be an area of interculturality.

Source: Based on Rathje, Stefanie (2015). Multicollectivity – It changes everything. Key Note Speech at the SIETAR Europe Congress (SIETAR_slides_Rathje.pptx (stefanie-rathje.de)). Accessed 24 May 2021.

Figure by Julia Flitta (www.julia-flitta.com)

Despite this, the figure also shows that through mutual learning and an exchange of experiences during their teamwork they can develop their team culture and thus common conventions, plausibility and rules of normality in a common (e.g. professional) context of action. This means that the interculturality of this cooperation has already gone beyond the fluidity of interculturality and entered into a common culturality. In this context they will now no longer feel culturally different.

However, if B is a committed member of a religious community to which A has had no previous contact, and B invites person A to a celebration within this religious community after work, then suddenly the intercultural perspective in their relationship can dominate once more. Since both spheres of activity, i.e. professional and non-professional, are interlinked by the reciprocal relationship between the two actors, the way in which A and B interact interculturally in the external context described will influence their already culturalised reciprocal relationship (and vice versa).

However, interculturality is not only multivalent and relational, but also relative: The same (common) action context may be perceived by A to be intercultural due to his/ her inability to feel plausibility, familiarity and relevance in the situation, while B may not even notice this due to his perception of culturality and therefore perceived normality.

This is an example.

Starting in December 2019, a global pandemic changed the way people behaved on a global scale. For example, different regions in the world had different ways of greeting. Whereas some people would bow or shake hands, others might fold their hands or give a peck on the cheeks when greeting their co-workers or business partners. After the pandemic began, it became increasingly common to only meet virtually, rendering these forms of greetings obsolete. Colleagues from very different regions of the world thus started meeting in a ‘blank space’, and needed to create a new cultural norm when meeting online. Different forms popped up, from a simple ‘hello’ from everyone to a ‘check-in’, in order to share what is on their mind before the meeting starts, and many other forms in between. As the pandemic has created a new reality for many of us, a new consensus on the way we communicate had to be designed, or culturalised.

Against this background, structure and process approaches can contribute to the realization of intercultural action as a goal-oriented and negotiation-based collaborative activity, which can help to create a new normality in a team, even when the team was previously perceived to be heterogeneous.