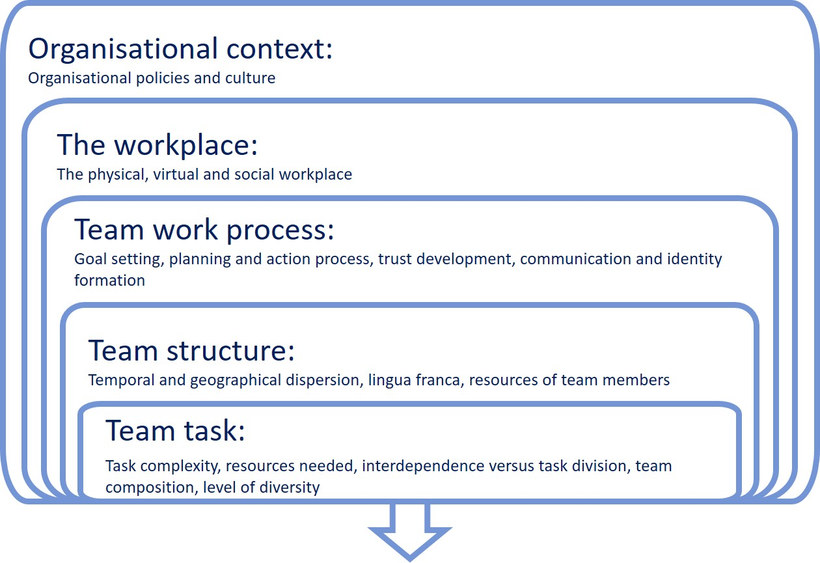

Working in virtual intercultural teams is complex and very often perceived as ambiguous, since, for example, team processes might be unclear, team members could be unfamiliar and the task at hand may not be precisely defined. VI teams are complex due to the tasks' cognitive and emotional demands. And what often goes unnoticed is the fact that virtual teamwork is multidimensional. The work and therefore team success is also influenced by a range of factors not immediately linked to the teamwork itself, such as the fact that team members are embedded in a wider organisational context.

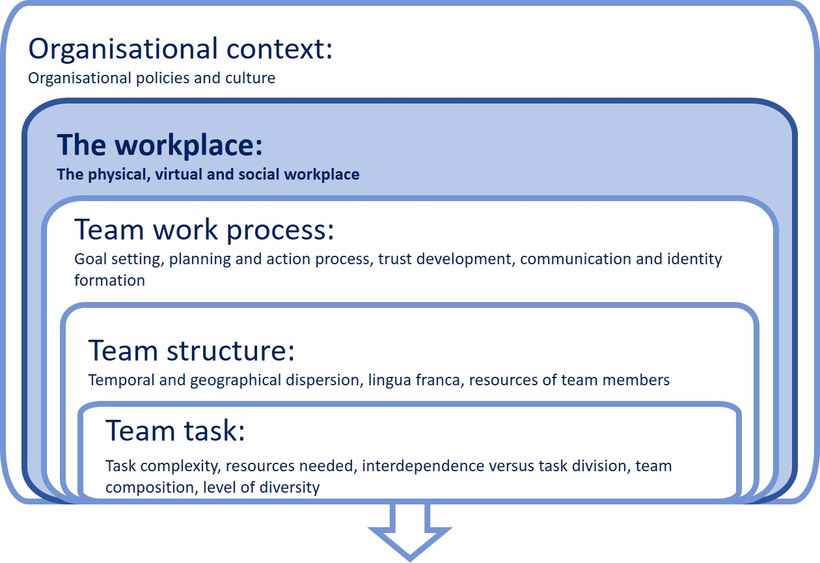

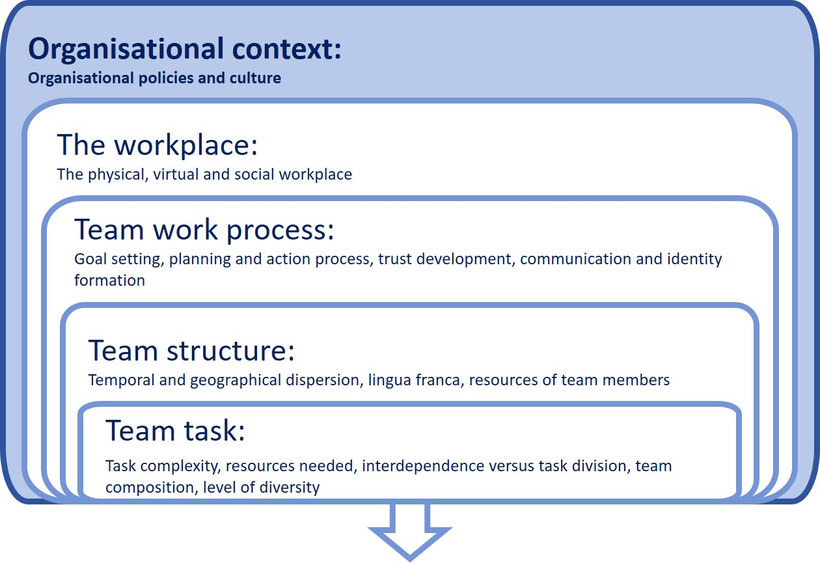

When analysing key challenges in virtual intercultural teams, there are five interlinking areas that require attention:

- Team task

- Team structure

- Team work processes

- The workplace

- The organisational context

Source: Based on Bosch-Sijtsema, Petra, Virpi Ruohomäki & Mattie Vartiainen (2009, p. 12)

The team task

Source: Based on Bosch-Sijtsema, Petra, Virpi Ruohomäki & Mattie Vartiainen (2009, p. 12)

Let us start by looking at the team task as it determines the primary focus of team members' activities and the coordination required. Because team tasks can range from routine to creative and problem-solving in nature, the task also sets the parameter for the resources needed in terms of knowledge, skills and competencies. In addition, the task itself also determines the workflow structure and demands in terms of coordination requirements.

Some of the challenges a VI team faces are developing a common understanding of the task and its complexity and establishing the resources needed to achieve goals as well as identifying those tasks which require collaboration and those which do not.

Even if the team decides on a high level of task division and independent work, there seems to be a consensus that a degree of interdependent working initially supports a feeling of connectedness and cohesion. Further, it fosters the development of trust and common communication patterns and can thus be a strong enabler of team performance. What often goes unnoticed is the fact that higher levels of interdependence and task complexity require greater effort with regard to communication and coordination within the team.

In a nutshell it can be said that the team needs to develop a common understanding of the task and its complexity, the level and specificities of task interdependence and an awareness of the time required for the additional coordination and communication effort.

Usually the team itself is put together in line with the specific task. For this reason, the general team composition will also be considered here. When viewing team composition, an important aspect to consider is the multi-faceted concept of diversity. In this regard, a key issue to be raised in a team is therefore: 'Which diversity factors might stimulate or hinder team performance and satisfaction?'. The answer could include aspects such as gender, the asymmetric distribution of skills or experiences, length of remote work experience, as well as cultural and language differences. The challenge to be met here is simply that of making diversity issues known, addressing their possible influence on the outcome of the team’s task, discussing integration processes and finally how diversity might be transformed into concrete benefits for the team. Developing a cultural profile of every team member as presented in the previous session is a first step in that direction.

Task: Identifying challenges

A French company produces lighting systems for private home use. The marketing team consists of six people at headquarters, plus two to three people in 10 countries where the product is sold, scattered around different continents. The entire global marketing team consists of 30 people. The main goal of the marketing team is to support the sales team in selling their product. In order to do this, following sub-tasks have been identified:

- The team needs to take the main messages that have been developed by the head office, and find a way to localise them to fit local consumers' needs.

- The resources need to be allocated: How much of the budget will each country receive, considering the potential of their market, and the costs associated with marketing platforms and materials. The head office also has the feeling that some locations simply shout louder in their demand for more resources, and assume this might have to do with the cultural diversity of the team.

- The global team needs to be on the same page when it comes to collaboration tools, the information flow from head office and the general processes regarding developing and adapting marketing materials for their respective markets.

Read through the short case study and think about the respective importance of the following aspects:

- task complexity

- resources needed

- interdependence versus task division

- team composition

- level of diversity

Please assess all of these aspects on a scale from 1 (= very low) to 10 (= very high). How would you rate each aspect, and what would your reasoning be for this? In which processes and tasks would it make more sense for the company to stick to the the general standards from head office, and which ones would be better localised?

Note down your ratings and the answers to these questions in your learning journal.

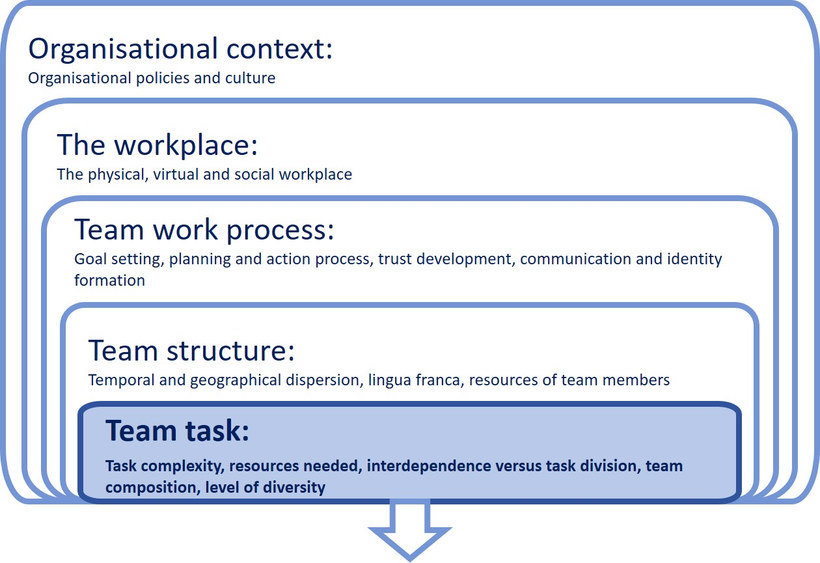

The team structure

Source: Based on Bosch-Sijtsema, Petra, Virpi Ruohomäki & Mattie Vartiainen (2009, p. 12)

The team structure refers to the properties of the team and includes aspects such as team size, temporal and geographical dispersion, knowledge of the lingua franca used, and the resources and experiences brought to the team by the individual members. According to studies by Bosch-Siijtsema et al. (2011, 2009) these items can simultaneously be enablers and disablers of team performance and satisfaction. Let us examine them in more detail.

Temporal and geographical dispersion: While time zone differences offer the possibility of 24/7-productivity, they are a challenge for teams because they need to find common working hours and synchronous appointments. A normal workday for one may be midnight for the other. This in turn may mean that work days are extended for some team members in order to catch up with others in a different time zone. There can therefore be a mismatch of day schedules, leading to delays and missed information, all of which influences the communication process within the team.

Time allocation therefore requires careful planning and consideration. The following quote highlights the need to recognise different public holidays and other periods of slower paced work such as the summer season or vacation time:

When the person is on a vacation, they actually do not work at all, so the project STOPS for that time. When there are many people consecutively taking vacation we could go 2 or 3 months without any work being done, which I wasn't expecting. Japanese companies’ employees don't take this many vacation days.”

(Source: Nurmi, N. (2009). Unique stressors of cross-cultural collaboration through ICTs in virtual teams. In: B. T. Karsh (Ed.), Ergonomics and health aspects of work with computers. EHAWC 2009. Lecture notes in computer science, Vol. 5624. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-02731-4_10, p. 85)

The quote is interesting because it seems as if the writer anticipates that when working on a project, work continues regardless of whether one is on vacation or not and there seems to be a difference as to how many vacation days are commonly taken.

Because geographical distance and in particular different time zones influence the frequency of meetings, this in turn is likely to influence communication flow. Virtual teams therefore need to pay particular attention to the impact geographical dispersion may have on virtual teams in order to avoid a lack of coordination, process delays and reduced feedback cycles.

The vast majority of virtual intercultural teams, as well as most multinational corporations, mandate English as a common language. Using English as a lingua franca of course has the potential to facilitate international corporation. However, it should be acknowledged that the use of English may also cause a lot of stress. This includes issues such as the status imbalance felt by non-native speakers in the presence of native speakers, language performance anxieties, and the potential for communication break-down, leading to inadequate sharing of knowledge and adverse sub-group dynamics. The fact that a single misunderstood term can impede significantly on a relationship is expressed by the following quote, related by an American interviewee:

“[After] four days of meetings and disclosures, a [native English-speaking] person wrote a summary of the meeting and a letter thanking [the French collaborators] for the meeting and so forth, and the last sentence was, ’Maria, we found this meeting to be invaluable.’ And the whole thing collapsed, people were just furious that the perception was that they had come to the meeting and the whole thing was seen to be not valuable. In English invaluable means you can't do without it, it was very valuable. And in French, in means not, and it took weeks to undo and get that whole [collaboration] back on track again, so in language issues one word can completely destroy [everything].” (Nurmi, 2009, p. 83)

Reducing the impact of language barriers through enhanced awareness and by giving each other language support is therefore an invaluable (!) task. The aim of every team should be to develop a safe language climate, which makes people feel included, as the following quote by Jukka-Pekka suggests:

How can Finnish engineers understand what people want in China? No, we can’t. That’s why we have Chinese team members in the project and their knowledge is so valuable for us. We just need to make sure that they share all that information with us over the language barriers and all. […] Everybody is not equally fluent [in English] and we must make sure that everybody understands by asking questions, writing, and using simple language. Video is also important because when I see that somebody doesn’t understand I can immediately react to that by specifying and repeating what I just said. (Nokia R&D, Finnish team member) (Nurmi & Koroma, 2020, p. 7)

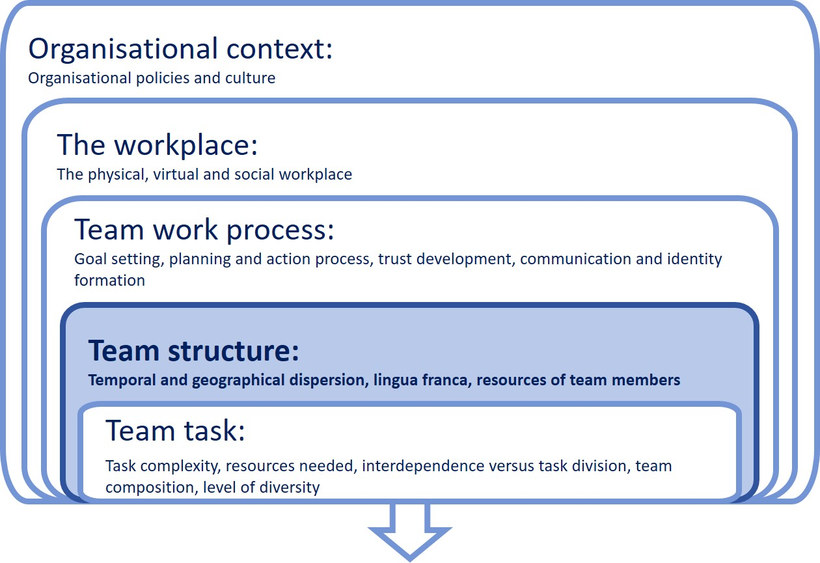

The team work process

Source: Based on Bosch-Sijtsema, Petra, Virpi Ruohomäki & Mattie Vartiainen (2009, p. 12)

The layer team work processes goes hand in hand with team structure, and refers to team members' interactions and how they use the resources available to them in order to meet the tasks and contextual demands.

They are therefore vital for the team’s success and an important aspect of team effectiveness. In accordance with the study by Bosch-Siijtsema et al. (2011) on knowledge workers in distributed teams, the focus here is on the behavioural aspects of team processes and thus the question of ‘how’ teams use their resources and how they manage to perform well. Activities that we can focus on here are, for example, goal setting, planning and actioning, determining of the communicate style, ensuring participation and monitoring, information sharing and reflection, developing a common identity, trust-building and achieving team satisfaction. In the literature, trust and communication as well as team identification and cohesion are often singled out as the major challenges to be met in order for the team to perform well and will therefore be considered here in more detail.

Trust has been studied extensively in this area for two reasons. Firstly, many factors that might support trust development in a collocated team are unavailable, making trust development particularly challenging. Secondly, virtuality requires more trust, since control mechanisms are lacking. For example, it is difficult to check work progress when team members are not sitting next door. Spatial distance sometimes requires team leaders to transfer responsibilities to unknown team members, despite the fact that this would normally require a significant level of trust. Team members who take on responsibilities must in turn have a high level of self-motivation, discipline and self-management skills because they largely have to fend for themselves. This is particularly difficult for employees who work well with clear instructions from their superiors or who flourish through the “social control” provided by the co-presence of others.

Physical proximity promotes trust-building by allowing individuals to directly observe what others are doing, which is hardly possible in a virtual environment. In a face-to-face conversation, subtle nuances and nonverbal communication signals, which are unconsciously and unintentionally conveyed are usually omitted in the virtual context. However, they do provide valuable information about the other person on a social level, such as personal characteristics, demographic features, social and professional status, strengths and weaknesses, etc. In addition to this, information on the environmental context within which each team member interacts, such as individual working conditions, is often missing. For instance, a teammate may be perceived to be slow to respond to e-mails or requests for information and this can quickly lead to judgments about the person not being reliable or trustworthy. However, knowing more about context issues such as, for example, home teaching requirements because teachers are on strike, public holidays or technical problems might have allayed the pre-judgment.

Another aspect hindering trust development when working virtually is the limited number of contacts experienced in comparison with collocated teams. Spontaneous interactions, e.g. running into a teammate or meeting by chance in the kitchen or at the water cooler, are largely eliminated.

It is commonly argued that the development of trust requires certain conditions to be present, such as time, physical proximity, mutual information exchange, a shared social context, common values and similar cultures. These conditions are rarely met in the context of virtual teamwork. So how can a team deal with the challenges of trust development? One approach is surely to leverage 'swift trust', which generally refers to trust built on role-based interactions. It refers to the fact that we can assume that team members share a notion of ‘we are all in this together’ and that getting the job done well will reflect positively on everyone. If a team is able to maintain this notion throughout the period of working together, then profound trust can develop and carry the team through the entire period of working together.

Because there is a tendency for people to trust those who appear similar to themselves and behave in a similar fashion, sharing cultural profiles that reveal information about ourselves helps to establish commonalities, which might include shared hobbies and other outside interests. Storytelling is another powerful mechanism to develop trust, and especially the stories that can identify with, such as how to deal with home-schooling, can be effective.

Agreeing on communication patterns is another important step on the path to ensuring trust, for example by letting other people know when you are unavailable or unwell for example. Although it is common to work with a common calendar, simply letting team members know when you have, for example, a throbbing headache and are therefore unable to respond as anticipated could make all the difference.

The relevance and influence of trust on communication and therefore task completion is illustrated by the following quote:

It also affects the reciprocal process of knowledge sharing and thus the team's overall effectiveness and performance. It helps to reduce conflicts. If trust is high, the information exchanged may be more accurate, comprehensive and timely. In a virtual team, trust reduces the high level of uncertainty endemic to the technological environment. As described above, trust is dependent on the degree to which you get involved and communicate openly about yourself as an individual, the more your team mates know about you, the more they can assess you and develop trust in you and your skills.

Source: Learning journal, 2020

Virtual teams that do not have the opportunity to meet face-to-face don't necessarily suffer from an atmosphere of suspicion. It is, however, particularly important that they pay close attention to the lack of opportunities for trust-building and that they are be pro-active in this area, making a special effort to create an environment that fosters the development and maintenance of trust.

Task: What makes me trust my team?

There are a number of criteria we can apply in order to assess trust in virtual intercultural teams.

Read through the criteria mentioned below and, in your learning journal, rank them according to their relevance, from 1 (= highest relevance) to 10 (= lowest relevance).

|

Competence |

Trust based on the perception and understanding that team members possess the required skills and competencies |

|

Compatibility |

Trust related to commonalities, such as values, approaches to teamwork, work and communication styles, interests and goals |

|

Integrity |

Trust based on the understanding that other team members keep their promises, are committed to cooperate and work towards the common cause |

|

Good will of all |

Trust based on the belief that everyone is concerned about each other’s well-being and makes constructive comments in this regard |

|

Inclusion and integration |

Trust based on the feeling and observation that everybody makes an effort to include and welcome all team members |

|

Well-being |

Trust arising from the feeling that other team members mean well and that there is nothing to fear from the team |

|

Predictability |

Trust based on the understanding that team members' behaviour is consistent, regardless of the context, stress level and project phase, and that they will complete the tasks they have been assigned to do |

|

Sharing of knowledge |

Trust based on the notion that team members don’t hold back information and are committed to knowledge sharing |

Figure developed by Thu Phuong Vuong for this course

A vital aspect of any team is communication. In this regard we should focus particularly on the perceived quality, quantity and frequency of communication. Some authors even consider communication to be the greatest challenge to be met when working remotely. To start with, communicating virtually is fundamentally different from face-to-face communication. It is often considered to be more complex than traditional in-person team structures due to the lack of physical presence and the resulting necessity to use technological devices as a mediator of communication. One of the main differences between a co-located team and a virtual team is that the former enables daily face-to-face interactions, whereas interaction in the latter must be intentionally created as the following quote highlights:

"Communication is not conducted in the classical way, like when you sit at your desk and say: 'Hey, take a look here'. Instead you have to use some tool, either Skype or Slack or whatever, in order to talk to each other and THAT is always a HURDLE. Depending on what kind of person it is you are not just talking to him, but you are writing to him. For some reason it FEELS different."

(Translated from the German quote below)

"Kommunikation ist halt nicht so, wie es klassisch geht, man sitzt am Schreibtisch und sagt: ‚Hey, du, guck einmal kurz'. Sondern man muss eben eine Art von Werkzeug benutzen, sei es Skype oder Slack oder was auch immer, um ÜBERHAUPT miteinander zu sprechen. Und DAS ist immer eine HÜRDE, je nachdem, was es für eine Person ist, den dann nicht einfach anzusprechen, sondern quasi anzuschreiben. Es FÜHLT sich anders an, aus irgendeinem Grund."

Source: Randhawa, V. (2020), p. 57

Even if virtual teams have team chat rooms and frequent team meetings, they simply do not have the same frequency of synchronous, real-time communication as co-located teams. Instead, a considerable proportion of communication is asynchronous, i.e. it doesn't happen at the same time. On the one hand, asynchronous media enables team members to interact independently of time, which gives them a high degree of flexibility. It also gives them the time to formulate, reflect and, if necessary, translate messages and ask questions in a thoughtful manner. On the other hand, the use of asynchronous media causes delays and interruptions in the communication process, which can be frustrating if, for example, the team cannot continue without a colleague’s response.

Coordination and communication processes may become lengthy, even more so if time zones need to be considered when colleagues need to wait for feedback, which may lead to tasks not being completed in a timely manner. Especially in communication processes that require a high degree of synchronicity, the achievement of a common understanding can be considerably impaired. The lack of immediacy of feedback makes it more difficult to maintain individual participation in communication, because it is much easier for members to withdraw from communication, which in turn promotes the phenomenon of "social loafing" or “free riding”. Such behaviour is much more difficult to detect in a virtual environment than in a physically located team.

Communication in virtual teams is also much more susceptible to misinterpretations and misunderstandings. Transmitting, understanding and interpreting messages correctly is generally more complex when they are mediated through technology, since the use of technical media is always accompanied by a channel reduction or filter effect. For instance, reactions of team colleagues in the form of facial expressions, movements or sounds usually help to guide a conversation and build up a common understanding by showing whether a topic can be continued (e.g. if everyone nods and thus signals agreement) or whether there are misunderstandings, ambiguities and questions (e.g. if a team colleague looks irritated).

In virtual teams, depending on the technological media used, these signals are partially or completely absent and would have to be explicitly formulated. This, of course, rarely happens as these signals are mostly produced subconsciously. The lack of such communication signals makes it more difficult to interpret a message correctly, which leads to problems of understanding. This is even more challenging for team members who rely on subtle, indirect communication through body language, gestures, facial expressions and proximity. A lack of signals also makes it difficult to assess the importance or urgency of a message, which can lead to a high-priority matter being given lower priority and vice-versa. For all of these reasons, effective communication in virtual teams often requires time-consuming queries and clarifications, which can create dissatisfaction and delays in the task completion process.

Studies show that virtuality gives rise to a number of communication challenges such as:

- the communication mode to use;

- expectations with regard to timing of feedback;

- the lack of a common frame of reference for all team members;

- differences in interpreting and perceiving messages;

- fewer nonverbal cues.

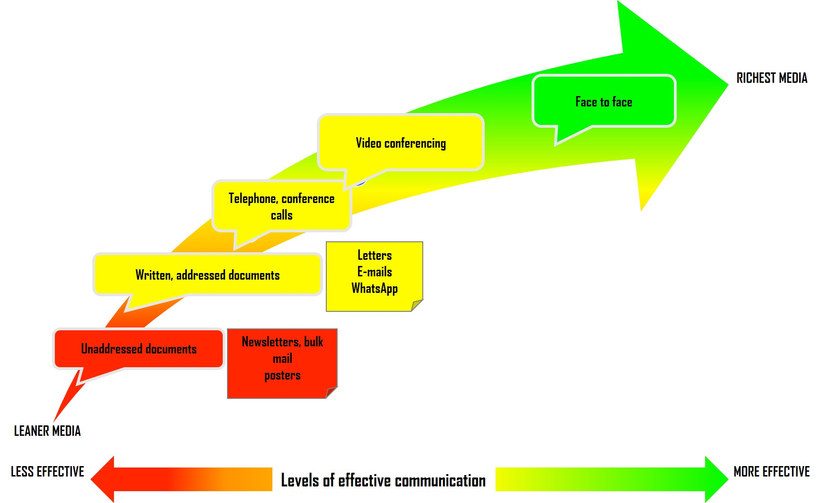

A major task for teams is therefore to clarify and determine how communication processes can best be established, and which communication tools to choose from for each particular situation. To this end, it is helpful to examine the level of richness involved in various media formats. The following illustration attempts to reflect this:

Source: Based on Ehsan, Nadeem; Ebtisam Mirza & Muhammad Ahmad (2008). Impact of computer-mediated communication on virtual teams‘ performance: An empirical study (Conference paper). In: International Scholarly and Scientific Research & Innovation 2 (6), 2008. Accessed 7 September 2021

Rich media such as video conferencing has several advantages such as its ability to convey verbal, para-verbal as well as non-verbal cues, support bi-directional communication and also allow for immediate feedback. It is therefore often used as a substitute for face-to-face meetings as it facilitates interaction and feedback. Communicating through video conferencing also gives team members a feeling of being 'close' and due to its high level of social presence, it usually supports effective communication and is therefore considered to create and support trust. However, team size, time zone differences, efficiency of time and the nature of the task all influence the attractiveness of video conferences. A tool very commonly used for sending and receiving messages in between calls or as a substitute for video-conferences are emails.

However, e-mail messages can be easily misunderstood and sometimes these misunderstandings have the potential to escalate into conflicts, as an American interviewee, cited in a study by Niina Nurmi (2009) warned:

"The written word can be very dangerous when you're dealing with the team at a personal or interpersonal level … especially if it's something that'll upset them, they'll read it again and again and every time they read it they will reinforce their own understanding, which may be the incorrect understanding."

Source: translated from Nurmi, N. (2009), p. 83

In the same study another American interviewee reported that the most stressful problems in his teams occurred when e-mail messages were misinterpreted and taken personally, noting:

"There are connotations in e-mail. The way things are written may be interpreted incorrectly. Especially working internationally, when there are different languages, different translations of words, and different meanings. A person from America or an English speaking country would interpret a sentence it in one way, whereas if you sent that same message to someone, say from Finland, the context may mean something DIFFERENT to them. And often, I think that’s where we begin to have problems as a group, i.e. when people begin to take messages personally or misinterpret them. That’s when the biggest problems occur."

Source: translated from Nurmi, N. (2009), p. 83

It is also very understandable that in a time of stress, emails may be written with less consideration of the receiver and even less care with regards to the words and expressions used, which may then be misunderstood, as the following quote suggests:

"When [work] pressure gets extremely high, the American response will be an e-mail to Helsinki saying, [the] sky is falling in on us, we have all these things to do, if all these things are not done by next Thursday we all lose our jobs and millions of dollars and yada yada, whine whine whine... and then the Finnish response is, don't worry. And so the American gets that response and it's like, they don't understand, the world is ending and what do you mean 'don't worry', of course I worry, …. so someone who has not been [in the Helsinki office] and not seen what that ‘don't worry’ really means, will interpret that a little differently, and the Finnish response to that American [panicking] is to stop whining and get some work done. That's the difference."

Source: translated from Nurmi, N. (2009), p. 83

This quote not only shows how the saying 'don’t worry' can be misunderstood, but also that not meeting deadlines may have different implications depending on the organisational context in which team members are operating.

Tasks: Email messages

Background scenario:

You are a member of a marketing team whose task it is to develop a strategy to launch a new software technology in all its markets. Your company has subsidiaries in fourteen countries around the globe and you only recently joined the team. When you were asked to put together the proposal for the product launch, you happily took on the assignment. In order to complete the assignment, you are dependent on the contributions of all regional marketing directors. In one of your online meetings, you all agreed on the format, the level of detail and the deadline for submitting the information.

All but one of them have now supplied the necessary information in the requested format. But one of them has let you down and only provided you with partial information. Despite asking him repeatedly to supply the missing details, you did not receive them by the deadline you all had agreed upon. You feel trapped because on the one hand you are still fairly new to the team and don’t know the team members well, and on the other hand you feel that without the missing information your proposal would have some obvious weaknesses, for which you do not want to be made responsible. As a newcomer you are also concerned that this may reflect negatively on your performance. However, you only have 24 hours left before the deadline is due.

Task: Drafting an email

You are sitting at your laptop and start to draft an email. Before you do this, take a note of all the factors mentioned in the scenario which may influence the way you formulate your email and write them down in your learning journal.

Task: Changing perspective

Now put yourself in the shoes of the team member required to send the missing information. Read through the emails below and note down the answers to the following questions in your learning journal:

- Which of the two emails below would have motivated you to respond? (both, only one of them or none)

- Which factors influence your decision to respond to a specific email?

- If you had been the recipient of the emails below, would any of them have offended you? If so, why? Pinpoint the elements/terms/expressions or phrases that run counter tohow you would expect communication to take place?

- In light of the reminders the receiver of the mail has already received, which of the emails would you consider to be unprofessional? Why?

- Is there an email where you are unsure of its correct interpretation? What could have been reasons for this?

- What would you consider to be cultural about the emails? Highlight two aspects and explain why.

- What do you think are possible implications of the different written communication styles on virtual intercultural teamwork?

Email 1

Dear Sir,

I would kindly ask you to take the time to call me as soon as possible. Some issues regarding the information you submitted have arisen and I urgently need to discuss these with you.

Regards

Email 2

Joe,

Sorry, but as you may have sensed from my previous communication, there are major problems with your contribution to our proposal. Please call me first thing in the morning.

Talk to you soon,

Email 3

Dear Mr,

Thank you for the information you submitted, which is very useful. However, I would like to remind you that there are some significant details missing, which are relevant for the proposal that I am expected to put together and submit within the next 24 hours.

Could you please give some further information, taking into account the necessary details I mentioned in my previous communication? Allow me to stress the importance of this information and the deadline set.

Looking forward to receiving the information from you,

Thank you for your support,

Yours sincerely

Email 4

Dear Joe,

I would like to ask for some feedback with regard to the information I asked you to provide. As mentioned, the information provided was not entirely correct and I feel that we should talk about our communication processes in order to avoid such situations in the future, especially since our strength to perform lies in our teamwork.

Therefore, I would like to call you one of these days and talk to you about this.

Would Tuesday be a good day for that?

Thank you for your understanding

Email 5

Dear Sir,

Despite reminding you several times, I still have not received the details I asked you to provide me with in order to put the proposal together. The deadline has passed and I have submitted the proposal without your submissions, not having any other choice.

This has left me disappointed as our cooperation so far has not fulfilled my expectations.

I imagine there are reasons for your behaviour. Looking forward to your explanations.

Regards

(This exercise was developed as part of the European project ‘Intercultural competence for professional mobility’ ICOPROMO 20070918_B3E (ecml.at) 22.11.2020 and has been slightly amended)

Differences in communication styles, as we observed with these emails can easily lead to misunderstandings and even larger issues which need to be addressed. Understanding and being able to detect differences in communication styles as well as developing an awareness of one’s own communication style is an important precondition to ensure common understanding and meaning. The difference between a more direct and a more indirect communication style is expressed in the following quote from an internship report:

"The [...] rather indirect communication style was reflected in the way my supervisor would give me a new task. While my supervisor in my home office would simply ask me to do something ('Please could you prepare these documents as soon as possible?''), my supervisor in London often used a more indirect approach ('If you happen to have a free moment, please could you take a look at these documents?'). It took me some time to understand this and read between the lines in order to extract the actual task."

It is of course easier to communicate with respect and may be even adapt to other team member’s way of corresponding when the stress level is low. The fact that this is more difficult with time pressure and increased tension is indicated by the following quote from a virtual team:

"However, as the project continued and we had more and more tasks to do in other courses and the stress levels rose, the tone of voice sometimes also got harsher, louder and was not as kind as before. Even though we never saw each other in person, even via video conference I could see that facial expressions and the ability to listen and let other’s finish speaking changed when we had more stress with deadlines and workloads. Moreover, towards the end of the project the motivation levels decreased, which also affected our way of working together harmoniously and efficiently."

Source: adapted from learning journal, 2020

'Team identity' can be defined as the 'perceived oneness' of team members and the orientation towards a common focus and goal. It also embraces the understanding that acting as a team can achieve a higher level of performance than the sum of each member's individual efforts. Further, it is based on the notion that members feel that they are valuable for the team’s success and make relevant contributions. As such, team identity is based on the feeling that we are an accepted member of the team. At the same time, team members also need to be committed to the team and its tasks in order to identify with the team and draw satisfaction or even self-esteem from being a member. A team's identity and understanding of cohesiveness as well as a notion of belonging have been shown to be highly important and relevant for team effectiveness, motivation, good decision making, conflict management, open and transparent communication and a deeper level of satisfaction.

In short, a team's identity alludes to the question: 'Are we all in the same boat and rowing in the same direction?' A major challenge for a team is to develop an understanding that working as a team brings performance benefits and work satisfaction. This understanding also encompasses how such a team identity can best be developed and what is tied up with this identity.

The fact that team identity also fosters team satisfaction is expressed in the following quote from a learning journal (2020):

"Despite all the difficulties, or precisely because of them, our biggest achievement was our team development, because I learned a lot and reflected on it afterwards.

Although we had some difficulties and did not always perform optimally, we still managed to become a team and feel like a team. We supported and motivated each other and we all contributed to the task achievement the best we could. And we did not separate over issues…I learned a lot about giving and receiving feedback, my roles in a team, dealing with different personalities and possible conflict situations. Furthermore, I now understand the impact my actions can have on the performance and morale as a team and how to communicate my strengths and weaknesses in order to avoid problems from the start."

Task: A team identity

Read the quote above carefully and identify five major aspects which you think characterise the team’s identity. Write them down in your learning journal.

The workplace

Source: Based on Bosch-Sijtsema, Petra, Virpi Ruohomäki & Mattie Vartiainen (2009, p. 12)

It is also important to consider the workplace as a key factor that influences virtual intercultural teamwork. This is because the context each team member works in can both hinder and facilitate the achievement of team goals. Contextual factors encompass physical, virtual, technological as well as social and psychological aspects, with all of these factors being interlinked.

The physical space relates to the actual environment where work is conducted, which can be in an office, on a bus, in a café, home office, at the airport or any other place. The virtual and technological space refers to the collaborative work environment, consisting of the tools and media used ranging from e-mail, audio and video conferencing to collaborative work environments and the tools and software that facilitate this.

But although mobile technology has largely liberated us from being bound to a particular place, it is important that all team members have access to the same equipment as it is vital to remove any technical barriers that could present a major hurdle to successful virtual cooperation. The technological infrastructure should be set up, which means equipping the team with the necessary hardware such as computers, mobile devices, printers, etc. and software such as project management tools, collaboration software etc. The technology infrastructure must be compatible at all sites, including external organisations. Team members may further have different levels of technical proficiency and experience. Employees who feel less comfortable with technology tend to show lower quality contributions, lower participation levels and poorer individual satisfaction, so they require training to develop appropriate media competencies. Creating the technical prerequisites for collaboration, including expenditure on data security measures and software, can be time-consuming and costly and should ideally be done before the teamwork starts.

Task: A liberated work place

Look at the photograph and think about how the environment might influence the telephone conversation. Which type of work space would you prefer if you had to discuss serious and important aspects of your teamwork? Note down the answers in your learning journal.

Photograph by Adelheid Iken

The social space refers to the social environment in which team members work. This could be team members who share an office, proximity to management, as well as your family, for exam please, if you are working from home. And of course it makes a difference whether I am around co-workers or have my family nearby.

The following is a quote from an internship report showing how the social space and the virtual space at times may overlap and influence team communication.

We have weekly online team meetings and one day our boss was telling us about a meeting he had had with our headquarters. It was a very important meeting because offices around the world were required to cut down on expenses and budgets were lowered. However, his 5-year old son had a more urgent topic. He came running into the room, jumping on my boss’s back and very excitedly asked him whether his father knew what he got for his birthday. He obviously had just found his birthday presents. We all laughed and patiently waited until he finished telling us all about his new game.

Bosch-Siijtsema et al. 2011 refer to Variainen who adds 'psychological space' as another important space to be acknowledged in teamwork. It refers to the feelings and thoughts that are part of an individual’s own space and psychological well-being and therefore not necessarily a representation of reality. For example, if one of your team members receives a promotion for which he or she has been hoping for a long time, this motivational boost will surely influence the spirit he or she brings into the team, despite the fact that the promotion is not linked to the teamwork at all. This could, of course, also cause a distraction in his or her mind. The point here is the appropriate consideration of the mental space as an influence on how we perceive and interpret other space.

The challenge to be met is to acknowledge these different spaces as factors that influence the lens an individual uses to perceive the outside world. This lens, of course, influences his or her behaviour and reactions. For this reason it is important to share social and contextual information, as this helps us to assess and understand one another. This is especially true for the early phases in a team’s development, where team members still have very little information about each other and look for guidance and “tells”: Small cues can mean a lot.

The organisational context

Source: Based on Bosch-Sijtsema, Petra, Virpi Ruohomäki & Mattie Vartiainen (2009, p. 12)

The organisational context refers to the broader organisational system in which a team and the team members operate. At times, team members may come from different organisations or different departments and are bound to follow departmental or organisational guidelines and policies that limit and influence the scope of their ability to adapt, negotiate and develop new team-oriented ways of working, i.e. form a new team micro-culture. As such, the organisational context can be enabling but also disabling with regard to effective team work. In many instances the organisational framework determines areas within the teamwork that cannot be negotiated.