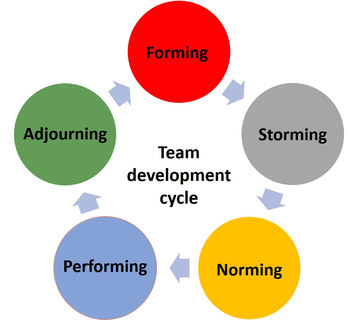

If we understand a team as a group of people who become interdependent and work together towards a common goal, then intuitively we can say that this team passes through a process of development, often referred to as a life cycle. The life cycle of a team indicates a series of phases that a team experiences until it reaches maturity. The most well-known model that tries to encapsulate these phases was developed by Tuckman back in the 60s, which includes four distinct phases of team development: Forming, Storming, Norming and Performing. Adjourning was subsequently added as a fifth phase.

Forming: This is an introductory phase characterised by participants' efforts to gain orientation and test out possibilities. It is therefore often also referred to as the ‘ice-breaking’ phase. The group shares information about themselves, gets to know each other, seeks orientation and initially tries to identify the boundaries of both interpersonal and task behaviours through experimentation. With regard to the objectives, the group attempts to define tasks through the identification of relevant information and respective ground rules relating to each task. All members further try to discover which interpersonal behaviour is acceptable to the group. Here they look towards the team leader, other members or existing structures and norms for guidance and support in this new and uncertain situation. The cooperation is often initiated with a virtual or in-person kick-off meeting, where group members introduce themselves and exchange initial information.

"I believe that this was the easiest stage we went through, getting to know each other better on a personal level. This stage might have taken a bit longer than usual due to the physical distance between us. We all had to overcome the initial shyness to build a team purely through virtual communication. But I think it was the right choice to put a lot of effort into this stage because it was the foundation for all the other stages."

Source: Learning journal, 2020

Storming: This stage is characterised, as its name suggests, by spirited discussions and arguments, more competitive behaviour and polarisation in interpersonal behaviour and at times conflict. Group members start to assess their own needs, and may attempt to put them ahead of the needs of the group. Similarities and differences between the group members become more visible and conflicts may emerge as the group tries to find suitable roles and responsibilities. There is a likelihood that group members disagree with the leader and with one another as a way to express their individuality. They tend to respond emotionally to task demands and exhibit resistance to suggested actions. Infighting and lack of unity are distinct features of storming. In a virtual environment it is especially important for both the team and the leader to develop sensitivity towards potential sources of conflict. This is even more critical in virtual settings due to the limitations on available communication channels.

"Looking back, this was the stage we really struggled and noticed the challenges of only communicating on a virtual basis. Brainstorming and having open discussions only in a virtual conference was difficult."

Source: Learning journal, 2020

Norming: This is the phase when the group has transformed into a cohesive team. It has overcome previous resistance and now, with needs of the various team members having been met, openness to other group members dominates the interaction, both on a task and personal level. Personal and more intimate opinions are exchanged and teams implicitly or explicitly recognise and agree on ways of working together and completing tasks, and rules are made accordingly. On the interpersonal level, members start to accept the group and the individuality of fellow group members, thus starting to form a team identity. In-group feeling and cohesion develop, new roles are adopted and new standards and norms are created through consensus. Cooperation plays a key role in Norming.

Performing: This is the stage when the team works together productively and focuses on producing results. Roles become flexible and the focus is shifted to the individual functions and competencies of the members in the group. Subjective relationships are established, the members adjust their behaviour to the goals of the group and respond to each other in ways appropriate to the task. Conflicts are used to test and align agreements. Constructive attempts to accomplish the task incorporate a variety of opinions and methods. The members are highly motivated and willing to learn from each other. The group, now functioning as a unit, concentrates its energy on the task at hand. A group needs to reach the Performing stage in order to be fully effective and utilise the competencies of the group members to perform at its best as the following quote indicates:

I noticed that during the course of time everything becomes a bit more emotional. People celebrate achieving their goals and the steps leading up to themTOGETHER. But also people get annoyed. You can see it when someone does NOT answer for a certain time, probably because of an unpleasant situation, or loss of enthusiasm.

(Translated from the German quote below)

B8 (l.301—306): "Und ich stelle schon fest, dass im Verlauf der Zeit das alles so ein bisschen emotionaler wird. Man freut sich GEMEINSAM über erreichte Ziele, Zwischenziele. Man ärgert sich. Man sieht, wenn jemand über einen gewissen Zeitraum NICHT antwortet, dass er vermutlich, wenn es eine unangenehme Situation ist, vermutlich eher weniger begeistert ist."

Source: Randhawa, 2020, p. 103

Adjourning: This is the stage when the project starts to wind down and team members complete their tasks. Team members' thoughts start to be diverted and the team is dissolved, or, if possible, reassigned to a new task. Under certain circumstances, the end may cause disruption, and in the process of dissolution, group members may experience feelings of sadness, uncertainty and appreciation of fellow members and the group might experience what could be called a type of ‘mourning’. There may be further self-assessments and evaluations of the group's success.

Critique

The team development phases outlined by Tuckman provide a generalised view of how a loosely bound together group of people moves through various phases of maturity in order to become fully effective. What it highlights is that the mere establishment of a project team is no guarantee for success and that it is crucial to acknowledge that team development is a process which needs to be sufficiently supported and promoted in order for the team to make the best use of the team members' competencies and experiences and thus achieve its full potential.

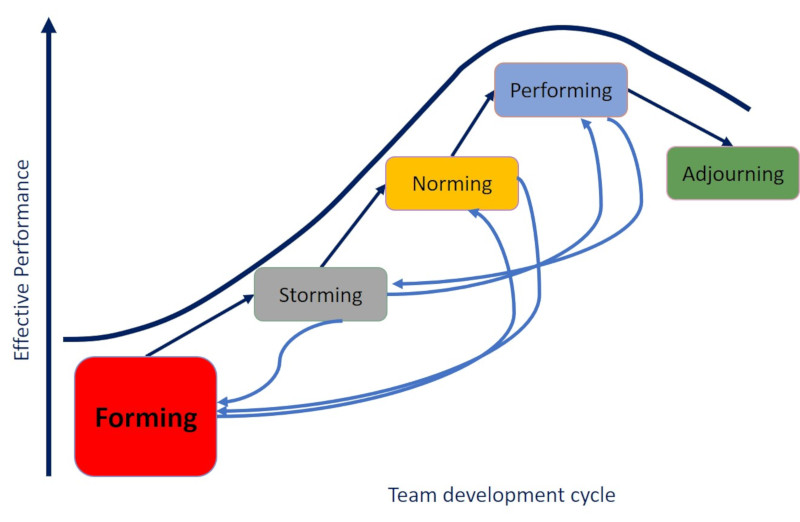

Crritiques of the model suggest that the linear development through phases cannot be supported by evidence. In reality, some teams shorten phases or skip them altogether. Furthermore, teams spend varying amounts of time in each phase and some teams find it difficult to complete the storming phase and move on to higher levels of development. In addition, it is not uncommon in practice for teams to jump back to earlier phases or start the process all over again as indicated in the illustration below. In reality, therefore, we can see the process as a constant and synchronous movement through all phases, albeit with a focus on one or two of the phases. It can also be seen that teams might become stuck in a certain stage of development, but can still reach higher development phases at synchronization points, and that sub-teams can be in different phases on a social level compared to the overall team.

Source: Based on Tompkins, Teri C. (2000, p. 212)

Task: Developing into a team

Think about a team you have been part of: Referring to the team life cycle, how would you illustrate or describe this team's development? Draw / paste the figure into your learning journal or note down the description in the journal (you can also do both).

Having completed this task, click on the following link to view a possible answer.

Show / hide sample answer

This is what one participant noted down:

In my opinion, after the stage of forming which was very short, we immediately switched to the stage of norming, where we decided on our goal, divided tasks, started researching and preparing the information.

The forming stage was rather short and a lot later we realised that we should have spent more time on this phase, and actually I would say through our small talk phase now and again we kind of moved back to the forming stage occasionally.

The transition between the norming and the performing stage was smooth and gradual. We were interacting respectfully with each other and our discussions were constructive, yet we were working eagerly and making good decisions. Later on, during the performing stage we at times developed an operational blindness at some point and realised that it would have been better to find out more about our team members. But because we reached this stage at a quite early stage of the whole project, we were still very motivated and wanted to give our best. So we didn’t mind that we kind of had to go to the storming and forming phase at that point.

Because we have not yet handed in our project, the adjourning phase is still to come.

The speed of the maturing process depends on factors such as the skills and competencies of the team members, the time available, the level of virtuality, the requirements of their tasks and the organisational context in which they work. Maturity cannot therefore be measured by time but by signs of group development and the ability of team members to develop shared meaning and working routines and learn from its work processes.

In view of the criticism, it needs to be acknowledged that groups are complex, adaptive systems that are driven by interactions among group members and that developmental paths can deviate from the ideal-typical course described by Tuckman. Some groups may not experience all of Tuckman’s phases or they may experience periods of stagnation, followed by periods of activity and subsequent development. Others may change the order of the stages or go through iterative loops as they loop back into earlier phases.

Nonetheless, the fundamental processes described within Tuckman’s phases are plausible: Every newly formed team needs an acclimatisation period during which the team members try to deal with the unfamiliar situation and strive for orientation and guidance. It also seems plausible that conflicting positions and needs arise over time and that these issues need to be dealt with in a "norming" process to ensure further cooperation, and that, if teams fail to handle these issues constructively, successful collaboration may be endangered. Finally, it seems realistic that teams do not immediately achieve the performance that is expected of them and that it rather takes time for them to mature, or indeed that the team never fulfils this potential. Moreover, the model is convincing in its simplicity and its intuitive character, as it is easy to understand and to apply. Despite the criticism mentioned, it retains its value as a simple tool for analysing and discussing team dynamics as the following quote suggests.

"Sometimes it helps to have such phases and to go a few rounds, then discuss it with the team and present a model, because it often results in pictures. Then I say: '[...] Every team undergoes phases of development and I even have an impression that we are at THIS point now. And what do you think?' [...] And then one can use such a model to show and ask, what it looks like for you?"

(Translated from the German original below)

B2 (l.130-143): "Manchmal ist es hilfreich, wenn man solche Phasen hat und man muss ein paar Runden drehen, dann das mit dem Team zu besprechen und einmal so ein Modell vorzustellen, weil das häufig so Bilder ergibt. Dann sage ich: ‚[…] Jedes Team hat Entwicklungsphasen und ich habe gar den Eindruck, wir stehen an DIESER Stelle hier. Und was meint ihr denn dazu?‘ […] Und dann kann man anhand so eines Modells aufzeigen, wie sieht denn das aus für euch?"

Source: Randhawa, 2020, p. 64

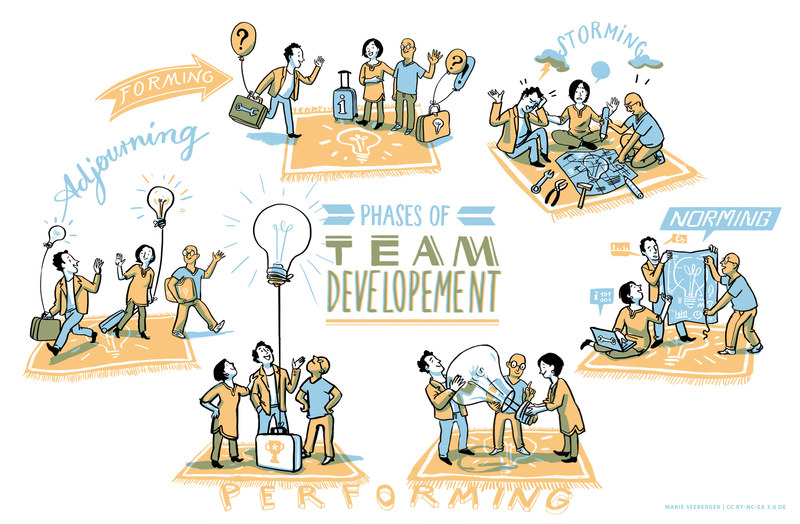

Illustrations by Marie Seeberger (http://www.behance.net/marieseeberger) CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0 license

Task: Central characteristics of team development stages

Look at the images of team development and note down central characteristics of the different development stages in your learning journal.

Having completed this task, click on the link below each image to view a possible answer for the respective stage.

Show / hide sample answer

Forming

This stage is characterised by:

- Novelty and the excitement about the project ahead

- Uncertainty and anxiety as to how things are going to work

- Frustrations because things seem to move slowly

- Members asking lots of questions

- Team atmosphere characterised by politeness as the team gets to know each other

Show / hide sample answer

Storming

This stage is characterised by:

- Team members challenging the validity of the task to be performed

- Slow advancement

- Tension between team members

- Disagreements concerning roles and responsibilities

- Negotiation of rules and work routines

- Some team members becoming very active whereas others are more laid back

Show / hide sample answer

Norming

This stage is characterised by:

- Considerable openness with each other and readiness to express real ideas and feelings

- Team members recognise, acknowledge and appreciate the variety of opinions and experiences among team members

- Starting to focus more on the task

- Team members appreciate to be part of the team and

- Develop their own team routines

Show / hide sample answer

Performing

This stage is characterised by:

- Team commitments to the task goal and collaborative teamwork

- Team members respond to each other in a conducive way

- Problems are solved in a constructive way

- Team members monitor its performance

- The team works hard and effective

Show / hide sample answer

Adjourning

This stage is characterised by:

- Team members slow down in order to prolong the project or speed up in order to finish before the deadline

- A feeling of loss as the team work comes to an end

- Concern and anxiety about the time after the project

- Appreciation of what has been achieved