Lane and Maznevski (2019) identified three steps that team members should move through in order to identify the resources available within the team and to use these to their full potential. These are mapping, bridging and integration (MBI).

Mapping involves detecting, describing and understanding the differences and commonalities among team members and the impact these differences might have on teamwork. The metaphor of mapping has thus been chosen quite deliberately since a map is an image that helps people to navigate a new territory. A map needs to be accurate and its level of detail and scale should be appropriate for the purpose of the journey. In our context we refer to a map that displays social features and whose data, in contrast to a geographical map, are difficult to verify. However, if they are carefully constructed and self-ascribed, such maps are very helpful, especially at the beginning but also during the entire course of the teamwork.

While mapping is about getting to know and understanding other team members, this understanding provides little benefit if it is not accompanied by bridging. Bridging refers to communicating and establishing areas of common ground among team members. In other words, it is the process of developing common meaning, while considering all the differences among team members.

The last step, integrating, refers to the management of differences and integration of the various perspectives among team members. The objective during this process is not just to resolve any differences, but to utilise them in order to generate added value and thus create new perspectives and practices as well as innovative approaches with regard to a task and its solution.

Let's look at each step in more detail:

In order to construct a map to illustrate the cultural makeup of team members, we first need to consider which factors should be included in such an analysis. People normally expect others to think and act in the same way they do themselves and usually that this is also considered to be the correct and best way. This, however, is a fallacy, as people have different approaches to all manner of issues such as conducting financial analyses, styles and channels of communication, ways of addressing short-term problems and resolving conflicts. At the same time, it would be wrong to simply think that ‘other people’ are necessarily always different.

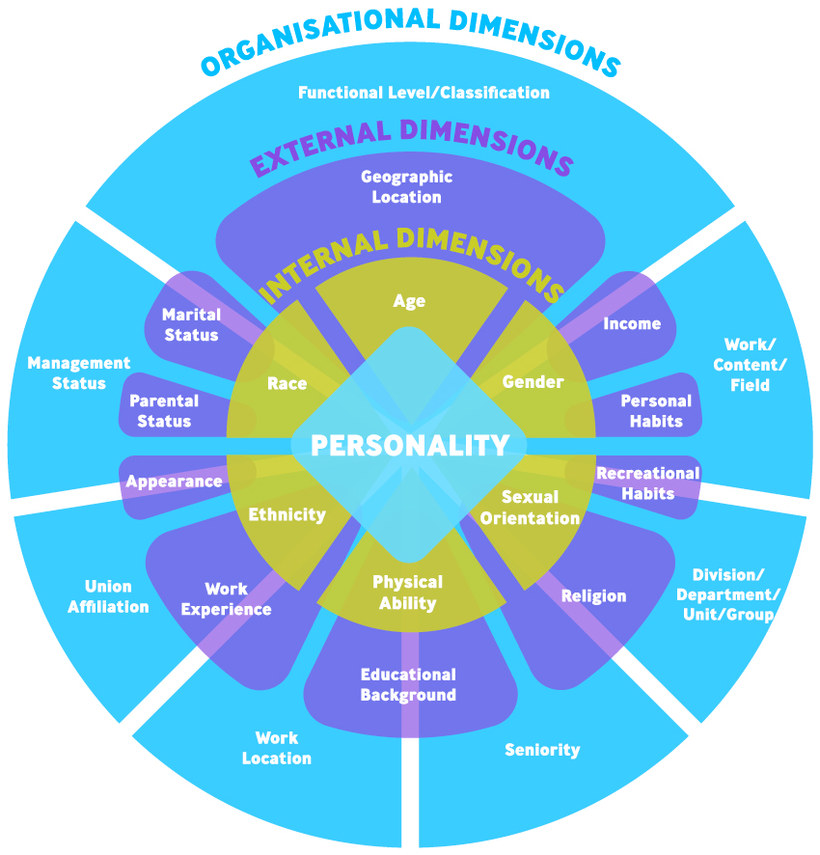

So therefore the question that arises is: ‘In which aspects might our team members differ?’ and ‘How many details do we need to know and which reference points should be used?’. There is, of course no general rule as to how thoroughly these questions should be answered, but points to consider are the level of virtuality and perceived differences, the complexity of the task, the amount of time at their disposal, the type of team, as well as the cultural awareness of the team members. A common tool to sketch out differences and commonalities is the diversity wheel originally developed by Loden and Rosener in the 90s. It is commonly used as an instrument for illuminating the areas of diversity that may be present in an organisation or team and it can help identify relevant collectives and diversity dimensions.

The introduction of the diversity wheel sparked lively discussion. One of the results of this discussion was a call for further diversity dimensions to be considered in the original wheel. The same discussion, however, also recommended limiting the number of dimensions outlined, thereby focusing on those which really make an impact on team performance and are therefore relevant in each particular context. The model below was developed by Gardeswartz and Rowe (2003). When using the wheel for mapping cultural differences in a virtual team, it is important to bear in mind that individual and group based differences intermingle in this model.

Source: Based on Gardenswartz and Rowe 2003, adapted

Figure by Julia Flitta (www.julia-flitta.com)

The wheel starts in the middle with personality, i.e. the characteristics of each person. This includes for example whether a person tends to be more extroverted or introverted, active or passive, but also how these factors influence interaction with others, and how the person is perceived by others. The internal dimensions relate to aspects that a person cannot influence such as age or physical abilities, and aspects which are usually not changed such as gender, sexual orientation and religious affiliation. In the context of the United States of America, race and ethnicity are also commonly included in this layer. All of these aspects are seen to have a bearing on how a person is treated and perceived by others during interaction.

The third layer depicts the outcome of life experiences and life paths. Commonly, ten dimensions are listed in this context such as education, income and marital status. Depending on how these aspects are valued by the corresponding interaction partner and whether they are seen to be connected, they may influence how these aspects interfere with or affect teamwork. The fourth layer includes elements that are linked to work and organisational contexts. They include hierarchical as well as functional aspects of working life and how a person relates to them in the context of diversity.

The diversity wheel is generally seen as an instrument to sensitise people with regard to diversity issues and make diversity visible among people who work together, thereby raising awareness but also understanding and acceptance. In the context of teamwork, the wheel may be used as an orientation to identify membership of collectives which might be influential when working together. For example, it might bring to light the fact that people in the team belong to different age cohorts. The critical point then is whether this is relevant for task performance and team satisfaction as well as what this may mean in terms of working together. It might also show that team members are very different with regard to their work experience. Digging deeper could show, for example, that some members have profound technical experience, which can be a real asset when working in a virtual environment. This means that the diversity wheel can be used as an initial means of orientation in order to assess which differences might be relevant. After this self-ascribed categorisation, the team can then assess what particular memberships of collectives might mean in the context of their teamwork.

One of the key insights from implementing this process is that that the factors contributing to perceived and real team diversity can vary from one team to another. Some factors will therefore be more or less relevant for teamwork, depending on the context. Also the factors contributing to diversity are not stable, but many of them can change over time. Coupled with the understanding that we need to acknowledge self-ascription and self-identification, the diversity wheel can be used as a basic framework and orientation to acknowledge differences and commonalities in a virtual team.

Task: My diversity wheel

Imagine you work in an intercultural and interdisciplinary team. Use the diversity wheel as an orientation framework and note down a few things you think you should share with your team members in order for them to get to know you well. Keep these notes in your learning journal.

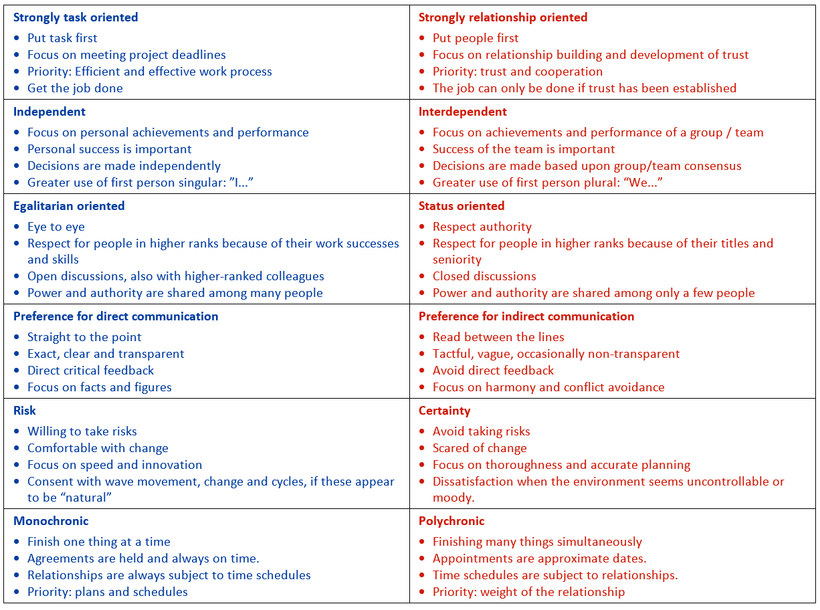

An important element in mapping is asking ourselves how we want to work together. Lane et al. (2019) introduce five cultural dimensions, elaborated by GlobeSmart, which they consider to offer a good combination of validity and practical relevance. These are: task versus relationship, independence versus interdependence, egalitarianism versus status, directness versus indirectness and risk versus certainty. Because virtuality is closely linked to real or perceived proximity and time differences, it makes sense to add the dimensions of space and time when mapping virtual teams.

When we use dimensions for mapping in this way, we acknowledge individual orientations as well as the images connected to individuals in a specific context. Mapping then takes place by locating people on a scale between a low and high level of orientation. This, of course, can never provide a truly accurate reflection of a person’s behaviour. One reason for this is that we have a certain understanding of the concept for comparison when we place ourselves on a scale. Developing a common meaning for concepts is thus an important pre-condition when using cultural dimensions for mapping. In addition, it is also possible that although we have a general cultural orientation, we may not behave in accordance to this in particular circumstances.

Task: The meaning of work

The following is a list of possible associations linked to work. Think about what work means to you and how people's different associations with the concept ‘work’ could influence working together in a team:

- Fulfilment

- Earning a good income

- Keeping myself busy

- Feeding my family

- Providing social contacts

- Doing something useful

- Gaining prestige and status

- Other

The first dimension, task versus relationship refers to the fact that team members need to take care of the tasks at hand. Thus, the question to be asked here is 'what needs to get done?'. The opposite end of this continuum would rather consider the social links between team members and their social well-being. In a team there may be members who primarily want to focus on the task at hand and whose priority is to produce results, thereby placing a lot of emphasis on goal setting, structures and schedules. There may be others who consider it very important to get to know each other before going about the task, thus focussing more on interactions in order to foster positive team relationships and the well-being of its members.

Whereas both are committed to completing the task, the ways of reaching this goal might be quite different. Task-oriented team members want to get started with their work quickly and consider relationship building as something which may develop as the work progresses. They are likely to be the team members who propose putting structures in place and developing a step by step plan in order to get the work done. They are also likely to be the ones who are very particular about deadlines, workplace procedures and reaching milestones. They tend to be task efficient and productive in particular at the beginning of team work. However, they may find it difficult to establish trust on a deeper level, which is particular important in virtual teamwork.

Task: Task vs relationship orientation

The following is a quote from a learning journal of a person who realised that there were people in the team who were task oriented and others who were more relationship oriented. Think about the potential issues this might bring to light:

"Some of my team members are completely focussed on task achievement, which does not leave any room for achievements on a team spirit or empathetic level, especially when members are not very open-minded. My personal wish and willingness to connect on a more personal level in order to establish a basis of trust was completely incompatible with the wishes and willingness of others."

In contrast to those who are more task-oriented, strongly relationship-oriented team members have a desire to get to know the team members on a more personal level and believe that if they know each other and understand the background of team members they are better able to communicate and avoid critical issues. This line of reasoning states that once a stable relationship has been developed and team members are being 'looked after', miscommunication is less likely to occur. Because they are willing to invest time and effort in meeting the team member’s needs and engaging in casual interactions, a non-competitive and conducive work atmosphere is likely to develop, which will support motivation and reduce dissatisfaction with the task at hand. They are likely to view a good relationship among team members and a positive work atmosphere as central to being able to deliver optimal performance.

The second dimension, 'independent versus interdependent' refers to the preference of working alone rather than coordinating with and helping each other to complete tasks. 'Independent' therefore means pursuing one’s own ideas and personal goals and staying in control of events. In contrast, a tendency towards 'interdependence' is based on the understanding that the task can only be accomplished through mutual cooperation and reliance. It highlights responsiveness towards the needs and expectations of others as well as a readiness to support other team members. In order to achieve this, a positive working atmosphere is key, as well as the feeling of a sense of loyalty and duty towards the other team members. It follows that team members who value interdependence over independence are likely to approach teamwork very differently. Interdependent team members, for example, are likely to require frequent interactions, assign roles as and when necessary and are flexible in their approach. On the other hand, independent team members are more likely to work confidently on their own and report back to the team when a scheduled task is completed. For them it is important that roles, once assigned, remain static and that rescheduling and flexibility remains at a minimum. Hofstede ID/IDV

Interactions are important for team members with both independent and interdependent tendencies, however the extent to which they value collective effort differs and will influence their assumptions towards the optimal way a team should work together.

Task: Different expectations

Read the following example and consider the different expectations inherent in having a strong notion of independence and interdependence.

Yunita is based in Indonesia and a new member of a project team that works virtually from different regions of the world. One of her colleagues is Kevin, who is based in the Netherlands. Kevin has been tasked with 'on-boarding' her, including answering any questions she might have in order to fit in well with the team. Yunita is very happy to have someone as competent and helpful as Kevin. For this reason she is surprised when she calls him again one day with a question, and receives the reply: "Yunita, I think I told you that a couple of times already. Look, I am really happy to help you out when you cannot help yourself, but I have a full desk of work myself. Could you please think about the solution yourself next time, and then get back to me when you really don't know the answer?"

Yunita is somewhat disappointed. From her point of view, being in a team means that she can ask colleagues who are simply faster at completing a task than others. The greater the mutual support in her opinion, the deeper the trust in the team would be. She would have been very happy to help Kevin with any task he might have for her, even if "he could do it by himself".

The third dimension, egalitarian versus status refers to how power and responsibilities are allocated and distributed. An equality oriented member of a team is one who believes that all team members are more or less equal and power and responsibilities should therefore be shared as evenly as possible. The assumption is that issues are discussed and decided upon together and that everyone is expected to contribute towards the task at hand. Organisations that have an equality orientation have flat hierarchies, which means that teams have a lot of independence and are allowed to make high level decisions. This means that they might even be able to decide on the recruitment of other team members, their compensation or performance assessment. The aim of such a working environment is to maximise employee commitment and bring out the best in each person.

Task: Hierarchical versus status orientation

The following quote from an internship report illustrates the hierarchical and status oriented structure within a team. Read the quote and answer the question as to how this might influence their teamwork.

"I perceived the work environment as very positive and the teamwork went quite smoothly. However, after some time I realized one thing that I was not used to and that is that the team structure is very hierarchical. Actually, everything works via titles. It is not just in the team itself. Throughout the company there is a strict path of upward mobility. Once you have finished a traineeship the first position or title is analyst. Next step would be associate, then senior associate followed by director."

Source: Learning journal, 2020

In contrast to egalitarian cultures, status oriented cultures expect decisions to be made by superiors and employees are expected to ask questions. Power and responsibility are distributed on a vertical level, which calls for a benevolent and empathetic team leader who makes decisions, maintains an overview of all tasks, allocates roles and additionally makes sure that the different parts fit together. In such an environment, team members expect to be taken care of and the team leader is the one who takes the blame when things go wrong as well as the praise when the work is done well. Team members who are status-oriented are likely to display a high level of sensitivity and respect towards other people’s achieved status, be it through education, performance or merit, but also on the basis of family background, age or heritage, for example.

The fourth dimension, directness versus indirectness, relates to a team member’s communication style. Somebody who values a direct communication style has a preference for frank, concise and to the point way of communicating. The aim is to be as clear as possible, leaving very little room for interpretations and ambiguity, thus ensuring swift and effective communication. This remains the case even when addressing difficult or critical issues, e.g. when giving feedback or when finding errors in the work performed. Direct communication is based on the understanding that the person and the message can be separated, thus avoiding embarrassment threats to a person's 'face'. Short and precise messages, written minutes of meetings and detailed instructions with little reference to non-verbal cues and interpretations are typical for this communication style.

"The physical distance between us due to online communication encouraged me to leave my comfort zone. It usually takes some time before I feel comfortable to open up to strangers and voice my opinion directly. But realising that we are all in the same situation and that I can trust my team members made it a lot easier for me. Not being able to meet in person taught me to approach people more openly and gave me confidence to voice my opinion in a collaborative way."

Source: Learning journal, 2020

People who have a preference for indirect speech use different ways of conveying the message and tend to communicate in a way that leaves room for interpretation. Pauses, silence, tone of voice, and body language are important parts of the overall communication. When communicating the focus is on the receiver of the message and an understanding that other people may have different views on the subject, that everybody operates within a certain context and that reading between the lines opens avenues for exploring areas of common ground without pinpointing any dissonance and thus avoiding embarrassment. Indirect communicators know that gathering additional information from sources other than words such as body language or context is required in order to grasp the meaning of the message. By ‘reading between the lines’ and using nuanced tones in communication, indirectness is very relationship and person-focused and aims at being respectful and showing courtesy to the receiver of the message. Face-to-face meetings and verbal agreements are typical for indirect communicators.

The fifth dimension, risk versus certainty, involves considering how much information is required before acting. Of course we all plan our actions, but how many details do we require and how much room do we leave for unforeseeable and unpredictable circumstances? Team members who are risk-oriented emphasise quick actions and are ready to go ahead on the basis of some basic information providing them with an initial orientation. They trust that through flexibility and the thorough monitoring of the a project's progress, they can make the necessary adjustments as they go along. Thus they are relatively tolerant to change and are usually not bound by too many rules and regulations.

The following is an example of how this difference may surface in behaviour:

Richard is an engineer with an upcoming presentation in front of an group of international colleagues. He has worked on his presentation for a long time in order to give his colleagues all the technical details they need to implement a new piece of software. After about an hour into his presentation, Jenny raises her hand and points out: "Richard, thanks for your presentation, but it is possible that you just tell us what the time is? You do not need to show us how the clock works."

Whereas more certainty-oriented people like to give and receive detailed information in order to make sure everyone is prepared for different scenarios, risk-oriented people perceive this as too detailed and unnecessary, since they are willing to simply try it out and learn from experience.

However, people with a preference for avoiding uncertainty need a thorough foundation of information and a detailed plan before they feel comfortable enough to commit themselves. This might include an intensive and detailed analysis of the project and the consideration of a wide range of different aspects and points of view, along with strategic planning and thorough preparation in order to be able to deal with all eventualities. During the implementation phase the focus is on following the agreed plan rather than adjusting it on the go. Having a detailed and agreed plan is perceived as creating transparency for all stakeholders with regards to objectives. In addition, milestones are understood as anchors to help visualise the progress of the project whereas rules and regulations give orientation regarding the behaviour and actions expected from each participant.

The last dimension to consider is monochronicity versus polychronicity, which refers to conceptions of time, a dimension whose impact on working teams is often underestimated. Since organisations and societies have become increasingly obsessed with the speed of work and therefore time, it is clear that time and the way it is experienced differently must have an impact on workflow and satisfaction within teams. For this reason it is essential to include a time dimension in notions of diversity.

"It bothers me when we run out of time. That’s why I like to start immediately after getting the task. Especially when we started our teamwork, one of my major personal needs was to clarify which member is responsible for keeping us on schedule and updating it with completed tasks so that we all have a kind of a structure which displays our progress and helps us to achieve our goals. My personal preference to get things done immediately and preferably be ready a few days prior to handing in the task also affects my course of action."

Source: Learning journal, 2020

With regard to the dimension of time, an important differentiation can be made between monochronic and polychronic time orientations. This refers to whether a team member feels comfortable juggling several things at once and has a tendency to multitask, or prefers sequential scheduling and the accomplishment of tasks one after the other. The following is a good illustration of this and also highlights that being more monochronic or polychronic can be a cultural orientation but also relate to a specific context.

The work of a hairdresser illustrates the polychronic orientation nicely. Especially in smaller saloons hairdresser need to try to maximise their time. This is why they are likely to attend to several clients at a time. One may be having her hair coloured, while another sits under the dryer and yet another is sent to have her hair washed at the sink. In between, the hairdresser takes phone calls and notes down appointments. A mail courier, on the other hand, needs to behave quite differently as not many of his tasks can be intermeshed and he or she has to complete one transaction before moving on the next one.

Source: Ballard, Dawna I. and David R. Seibold 2003. Communicating and organizing in time. Management Communication Quarterly, 16 (3), pp. 387.

Closely linked to this is the question of flexibility with regard to work schedules and the understanding of punctuality and deadlines. The other aspect of time relates to the notion of events versus clock time. The event time orientation refers to viewing time as cyclical and a continuous flow, where tasks are planned relative to other tasks and activities take place in succession from the past to the present and into the future. This means that you ‘call it a day’ not at a specific time, but when the work that you felt needed to be finished is completed. Clock time in contrast works according to precise schedules and activities are anchored according to time. This also means that days are compartmentalised into activities, e.g. what happens after breakfast at a certain time, etc.

Task: Opening hours

Look at the photograph below and think about when the shop is going to reopen and what somebody who is used to clearly defined opening hours would think about the shop owner.

Note down your thoughts in your learning journal.

Source: Iken, Adelheid, 2002. The photo was taken in Shanghai, China.

Trying to understand our own orientation with regard to the various dimensions and assessing which type of behaviour we would typically display or expect in teamwork not only promotes self-awareness; It also helps to grasp other team members’ perspectives and understand the lens through which they see the world. It also helps to make the network of shared collectives among team members more transparent. In sum, mapping provides a basis with which similarities as well as differences can be detected. It fosters an understanding of possible communication issues as well as potentials for generating added value. Therefore, it contributes to the enhancement of team performance and effective interaction.

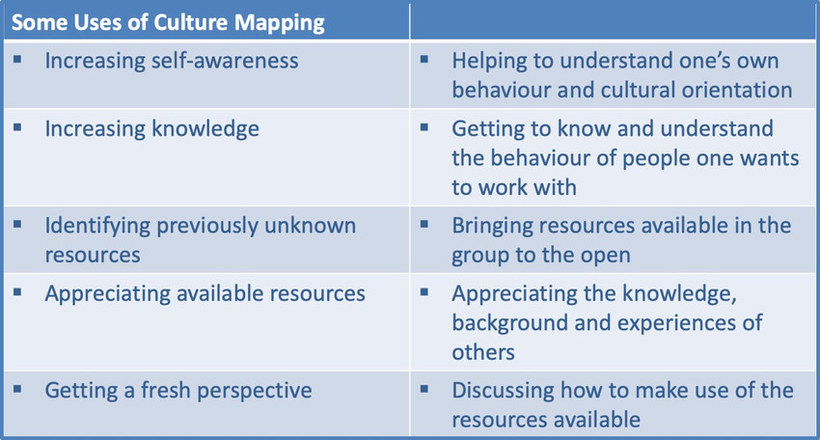

Many people question the importance of mapping and as Lane et al (2014) argue, there is a trade-off between investment and results. They acknowledge that mapping takes time but point out at the same time that it provides many opportunities for increased understanding, which may pay off at a later stage. The illustration below provides an overview of the benefits of mapping. When considering how much time to invest in the mapping process, criteria such as the degree of task complexity, team diversity and previous experience of diverse teams should be considered. Maps should be seen as flexible tools that can help us to understand our own as well as others' behaviour and may need adjustment depending on context.

The following table provides an overview of the advantages of mapping.

Mapping is a good and important starting point for bridging as it shows where relevant differences might be expected and where similarities exist. But mapping is useless unless it is accompanied by the willingness and openness of team members to accept that no one style and approach is better or worse than any other. When implemented well, mapping thus fosters understanding among group members and a positive approach to integration, which is the foundation for the next phase, bridging.

Task: Getting to know myself and my cultural orientation

Knowing yourself is an important stepping stone if we want to perform well in an virtual intercultural team, and the dimensions discussed can be helpful in achieving this. Using the scales in your learning journal, imagine a work context and position yourself on a scale of one to five.

Click on the image for a larger view

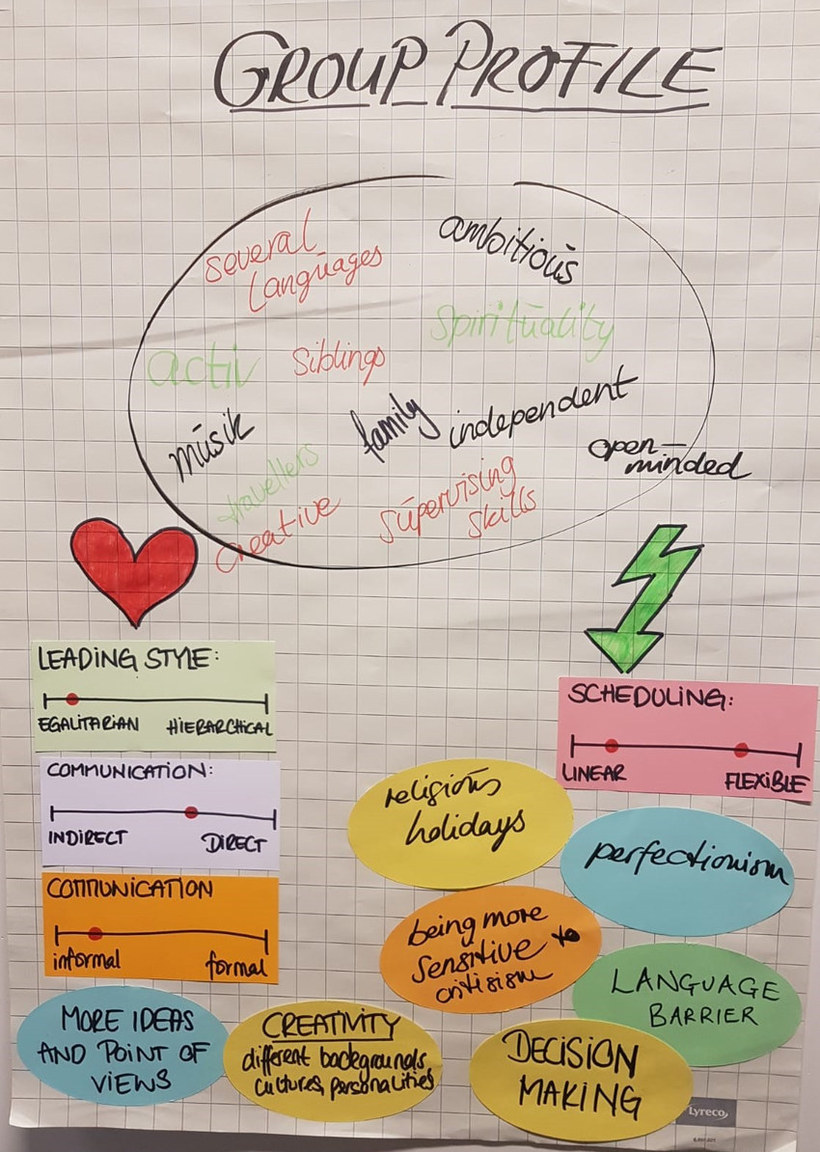

Once a team has shared its identity profiles, the next step is to identify central differences and commonalities. This can be done by developing a group profile together. The one below indicates commonalities such as all team members' appreciation of a polite, semi-direct communication style. However, they have different approaches when it comes to scheduling and therefore time orientation. In addition, there are certain events such as religious holidays which are important to some team members.

Source: Iken, Adelheid, HAW Hamburg

Bridging could be considered the most important step, as it relates to what Lane et al (2019) call ‘Bridging differences through communication’. The starting point is to understand and interpret correctly what the other people mean by their words and behaviour including perceived differences as well as commonalities. Let us imagine, for example, that all team members share the understanding that they want to communicate openly. In this case we need to examine what they actually mean by ‘open communication’. Further, we should consider which areas this ‘open communication' refers to. So one of the major tasks is to develop a shared meaning in regard to the issues at stake.

In this context Lane et al (2019) refer to engaging, de-centering and re-centering as central skills in order to move through the bridging process. Engaging relates to an open attitude as well as how motivated participants are to put effort into overcoming communication barriers while believing that this is achievable. De-centering is understood as moving away from our own position and centering, i.e. trying to understand and see things through the eyes of the other person.

Task: De-centering

On page 119 of their book "Organizational Behaviour" (2019), Lane and Maznevski quote a manager saying:

"I know that as a Chinese person it's hard for you to disagree openly with your boss, but I want you to know it's okay to do that with me. I don't mind when you disagree with me, in fact I expect you to."

Considering an open definition of culture, why can this not be considered de-centering? Note down your answer in your learning journal.

Having completed this task, click on the following link to view a possible answer.

Show / hide sample answer

This is what a participant noted down:

The manager acknowledges possible behavioural differences but he expects the Chinese to behave in a way which, taken the expected behaviour into consideration, must be difficult and possibly even painful to do so. De-centering means more than acknowledging behavioural differences, it means taking an approach which generates the information needed in a way which caters for different communication styles, in this case that of the Chinese.

In the example provided, this may mean asking "What alternative viewpoints could you envisage?" or "How do you think others may perceive this?".

In the context of de-centering, it is extremely helpful to share explanations of behavioural patterns and do this without blaming or making assumptions. This helps to bridge communication differences without making pre-judgments and thus opens avenues for a creative exploration of alternatives. This is also the step of re-centering, i.e. finding a common view of the situation and agreeing on common rules. Bridging is an important step towards developing a shared reality and team culture.

Take a virtual meeting as an example. Initially, each team member might have different assumptions regarding issues such as the reason for coming together, who should be part of the meeting, the relevance of the informal and formal part of the meeting etc. The team therefore needs to develop a common understanding of meanings and based on this develop a commonly agreed approach. If a team does not take the time to clarify these questions, its members may use the same term for very different things. This in turn may result in misperceptions and misunderstandings. However, by going through the re-centering process the team is able to develop common meanings, in this case, with regard to ‘meeting’ and the rules and procedures linked to it. They may even reach the stage of developing new approaches with regard to ‘meetings’, for example.

Task: The meaning of 'team meeting'

The following list specifies some possible meanings when referring to a ‘team meeting’. Think about what team meetings mean to you and how different meanings can influence your teamwork. Note down your thoughts in your learning journal.

A meeting can mean different things to different people, for example:

- a planned occasion

- a casual get-together to share work progress

- people getting together to discuss issues,

- meeting to enjoy sharing information

- people making decisions

- information gathering

- problem solving event

Integrating differences is the last step in the MBI approach. This stage involves benefitting from different perspectives and ideas and using these to create a high level of performance. Three key processes are of vital at this point: generating and ensuring participation, dealing with upcoming issues and building on all ideas available to the team. In the case of participation, it needs to be acknowledged that not every team member has the same norms with regard to contributing ideas and thoughts openly. There may be people who prefer to do this in a team meeting, others may prefer to do this in writing or in a one-to-one meeting, yet others find it easier if they are asked indirectly. Also the status of other team members may be a hindrance. There may be people who find it difficult to bring their ideas to the fore in front of the team leader. Therefore It might be advantageous to develop and agree on routines to facilitate and ensure everyone's participation – in other words, to develop a 'questioning' culture that everyone feels comfortable with.