Given our understanding of diversity and super-diversity, in any given situation in which two or more people meet it is very probable that there will be differing notions of a range of issues. These could relate to a different sense of belonging and identity as well as disparate experiences, value sets, expectations and action chains. The development of the concept of interculturality over the past decades has made us aware of this.

Before we continue, think about the following question:

When would you characterize an encounter as intercultural and why?

Our understanding of interculturality is linked to our understanding of culture (our culture perspective). There are two ways to approach interculturality: the closed perspective and the open perspective.

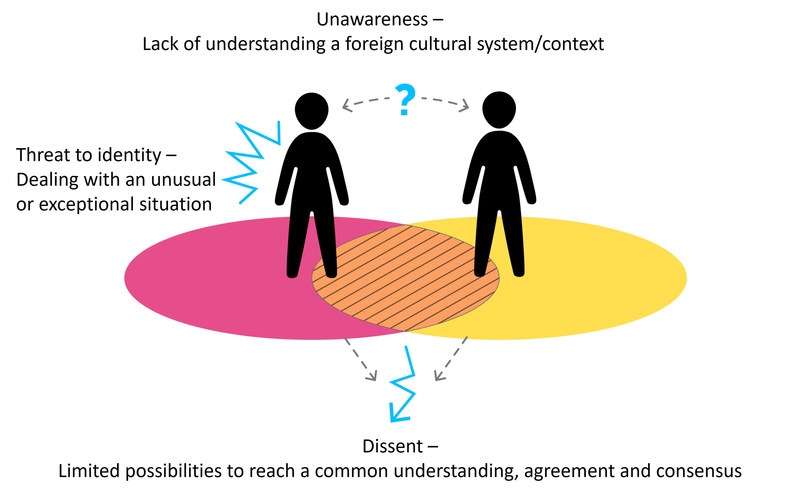

From the closed perspective´s conception of culture interculturality describes an interaction between participants from culture A and culture B. Participants from culture A and B perceive each other as foreigners and strange. From this perspective, "national culture" or "ethnicity" is the predominant force driving all decisions made in human interaction. Intercultural interaction is seen as action between two or more people from different countries with different cultures.

Source: Based on Rathje, Stefanie (2015). Multicollectivity – It changes everything. Key Note Speech at the SIETAR Europe Congress (stefanie-rathje.de). Accessed 24 May 2021.

Figure by Julia Flitta (www.julia-flitta.com)

'Otherness' is commonly held responsible for dysfunctional interaction and ineffective cooperation. Thus, culture and interculturality are seen as problematic. An orientation towards national cultures combined with efforts to find easily conveyed generalisations is risky, as one may take on stereotypical notions of a "national character", for example by characterising the French as vain and the US-Americans as superficial. Such generalisations can also be perceived as having a positive connotation as the following example describing the Dutch as being ‘gezellig’ suggests:

"Coming through the cultural aspect there is one word which describes the Dutch culture perfectly: ‘gezellig’. Directly translated, the word means ‘socialable’ or ‘cosy’, but actually this word has no accurate translation. Dutch people use this word to describe everything positive. A place can be ‘gezellig’, a room can be ‘gezellig’, a person can be ‘gezellig’, an evening can be ‘gezellig’. ‘Gezellig’ or ‘gezelligheid’ are less about a word and more about a feeling. It describes the moments of happiness, being together and to share beloved moments. I notice that Dutch people are very open and warm-hearted."

Usually otherness or strangeness is linked to misunderstandings, dysfunctional encounters and is held responsible for ineffective cooperation as the following quote from an intern indicates:

"I remember one time when Louis called me late in the evening and said that he needed the draft for the new flyer 'most urgently' and 'until tomorrow morning'. Then I sat all night finishing the draft so that he could take it the next morning. However, the next day he did not even show up at the office and when I called him later that day telling him the flyer was ready, he just told me to relax and wait. I was really annoyed and disappointed but thinking back at it guess this was an example of a cultural misunderstanding, as in Peru tomorrow seems to have a wider timely extension."

Interpreting "most urgently" and "until tomorrow morning" literally obviously and from the point of the intern understandably caused disappointment and frustration. However, whether this misunderstanding can be explained by referring to 'the Peruvians' needs care and closer examination. Applying an open concept of culture might not only have cast doubt on this assumption, but also opened up avenues to deal with the situation in a constructive manner through its understanding of interculturality as a negotiation process.

From the open perspective of culture, cultures simply exist within human collectives. As the term ‘collective’ includes all kinds of groups composed of individuals from football clubs to corporate organizations to nation-states, individuals have multiple belongings and are culturally heterogeneous. This approach differs from the closed ‘inter-national’ understanding of culture, which considers exclusively ‘national traits’ as in the above example.

With an open concept of culture, interculturality is an ongoing negotiation process (cf. Bolten 2015). This perspective offers a constructive approach for analysing and understanding the dynamics of intercultural communication in intercultural encounter. In the following we will discover why this is so.

From an open perspective interculturality can be characterised as follows:

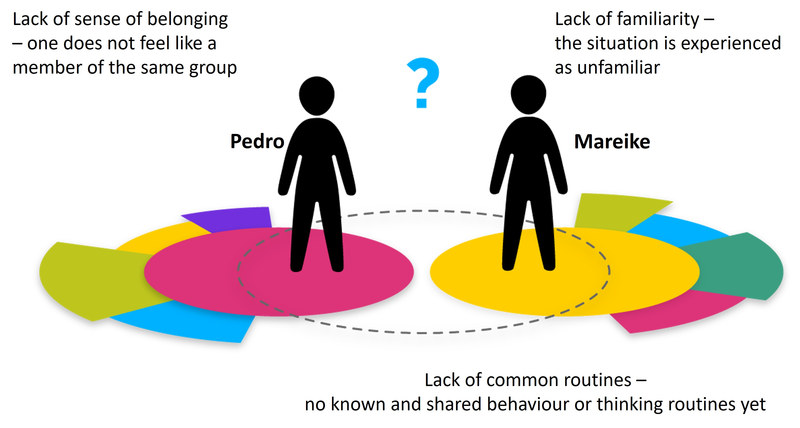

In an intercultural encounter individuals find themselves in a situation in which there is no normality, they cannot create any plausibility and routine actions are not possible. People who meet, may perceive each other or each other’s behaviour as strange and unfamiliar. This feeling of strangeness can be due to a difference of any kind and can include subtle things such as gestures, facial expressions, use of language as well as larger phenomena such as traditions, ways of dealing with issues, or the way an education and economic system is structured. In such circumstances it is quite normal that people judge the experience by comparing it to their own behaviour and what they expect and are accustomed to.

"I think the most obvious and most distinctive difference I experienced is the directness in conversations. The German culture is very direct. Conflicts and problems are approached directly, real opinions are given straight away and there is less talking around the topic. I experienced British people to be more discrete. It is very important for them to stay friendly. Feedback one receives always sounds positive and the negative aspects are not mentioned that clearly. There were situations where my colleagues and I were fuming about something another department said or did, but once we sat in the meeting to talk about it, everybody was joking around and the topic was approached as if it was not a big deal anyway."

What happened is that the intern experienced the communication style as unfamiliar, not necessarily as a threat but as different and possibly somewhat annoying and strange. She also based her experience on belonging to another group, i.e. nationality. The following illustration indicates this.

Imagine two people, let us call them Pedro and Mareike. Pedro is an international student and Mareike comes from the south of Germany. They are both in their first year at the university which has just started. They are given an assignment to work on and when they meet for the first time, they realise that what they have in common (yellow circle) is that they are fellow students and both have an interest in the subjects chosen. Apart from that they also realize that they belong to the group of people whose second language is English (indicated by the blue colour). When they meet to work with each other, at first they feel very insecure because everything is new, they don’t know what to expect and they are a little anxious that differences may prevail, which might make working together difficult. Because they do not share the same mother tongue, they also perceive themselves as belonging to different groups or collectives. When they talked about the assignment they also realised that they seem to understand the task differently and would therefore also approach the task differently.

Source: Based on Rathje, Stefanie (2015). Multicollectivity – It changes everything. Key Note Speech at the SIETAR Europe Congress (stefanie-rathje.de). Accessed 24 May 2021.

Figure by Julia Flitta (www.julia-flitta.com)

Two weeks later, the situation looks quite different. Pedro and Mareike not only feel a lot more comfortable at the university, they have also met several times and got into the habit of talking about the course for a short while before working on their subject. They have also exchanged WhatsApp messages (indicated by the pink area) and know that any time they can text message each other when there is an issue. Mareike is a member of a capoeira group (indicated by the green area) and asked Pedro to come along. As he really enjoyed being part of the group, they decided to go there together (indicated by the green area around the two).

Source: Based on Rathje, Stefanie (2015). Multicollectivity – It changes everything. Key Note Speech at the SIETAR Europe Congress (SIETAR_slides_Rathje.pptx (stefanie-rathje.de)). Accessed 24 May 2021.

Figure by Julia Flitta www.julia-flitta.com)

The degree of strangeness Mareike and Pedro experienced initially was probably not extreme. However, we still need to acknowledge that they nevertheless experienced a lack of normality, plausibility and routines at the beginning. So as we can see, in any new encounter there will be a level of interculturality. If not dealt with skilfully, people can feel threatened due to insecurity and anxiousness. As a consequence, it can even lead to people withdrawing from an intercultural encounter or avoiding meeting others.

In our previous session we defined culture as referring to groups of people, the boundaries of which are blurred. Within the group, people share a certain amount of knowledge and have developed a sense of familiarity and shared code system. This means that in an intercultural situation it is of paramount importance to establish normality and routine actions in order to make this interaction a stimulating and enriching experience.

In a nutshell, the term interculturality describes the absence of normality, plausibility and lack of routines. In an intercultural encounter, therefore, people with different concepts of normality, plausibility and routine actions meet and find themselves in an unfamiliar situation.

Task: Defining the term 'intercultural encounter'

What do the definitions have in common and in which ways do they differ from one another?

Note down your answers in your learning journal.

Sort the definitions / explanations according to their position on a scale of an "open" vs. a "closed" understanding of culture by giving them a grade from 1 (= most open concept) to 7 (= most closed concept).

Diagram developed by Yeliz Yildirim-Krannig for this course.

Now look again at your answer to the first question. Would you change your answer or add something? Note down your thoughts in your learning journal.

Having completed this task, click on the following link to view a possible answer.

Show / hide sample answer

Here is Olesia's answer:

1) What do the definitions have in common and in what ways do they differ from one another?

Some definitions refer to individuals as representatives of different groups (countries, etc.).

Others refer to behaviour or some experience of dealing with unfamiliar environment or representatives of this environment.

2) Sort the definitions / explanations according to their position on the scale of an "open" vs. a "closed" understanding of culture by ordering them from 1 (= most open concept) to 7 (= most closed concept).

1) encounter with my hidden assumptions of the other person's worldview

2) little common ground at first, understanding depends on communication process + context

3) participants differ in important aspects, experience of "otherness"

4) likelihood of feeling confused, offended, frustrated by the behaviour of the other person

5) contrasting views on what is proper and improper / socially unskilled behaviour

6) meeting somebody who is different / from another... (country, region, religion, cultural background)

7) dealing with and adapting to an unfamiliar cultural environment

3) Looking again at your answer to the first question, would you change your answer or add something?

Olesia added the following to her answer:

After doing the second part of this task it came to my mind that some definitions refer to other cultures and groups as the "other" meaning "foreign" and thus very different, whilst other definitions share a milder shade of meaning in the sense of unfamiliarity or difference.