In a given culture or collective, people share a repertoire of knowledge. This is knowledge that we acquire and use in order to make sense of the world around us, to interpret experiences and to generate social behaviour. As Hoffman and Verdooren (2019) argue, this can refer to practical ‘everyday knowledge’ in the sense of ‘this is how things are done around here’. This could, for example, relate to opening hours of shops and government institutions, traffic rules, and the legal and political systems. Imagine, you want to travel on the bus and are new in town. You might come across a system whereby you have to buy a ticket before entering the bus and maybe you would be able to do this via an app or by going to the nearest kiosk. In another context you may be required to buy the ticket on entering the bus or there might also be a ticket inspector. People familiar with the environment share this knowledge about ‘taking the bus’. As newcomers we may feel confused if ‘taking a bus’ functions differently to what we expect and are accustomed to. Being knowledgeable about ‘how things are being done around here’ is important as it helps us to manage day to day affairs.

When and how to greet people can be another relevant piece of everyday knowledge. Imagine you are doing an internship in an international company and on your first day your supervisor takes you around the office to meet your new colleagues. He stops at every desk and introduces the person to you. What are you going to do? Shake hands? Give the person a smile?

But cultural knowledge also relates to more abstract knowledge such as knowledge of philosophy, arts, history or science inasmuch as it is prevalent within a collective. Such knowledge can be the source of ideas, inspirations and discussion and within a collective can constitute what Hoffman and Verdooren (2019:28) call a group’s ‘frame of reference’ or a cognitive map. Such maps guide people to assess what is being considered as right or wrong and they contain some principles and an orientation regarding how to respond to and interpret such situations. This does not mean that they necessarily compel us to follow a particular course. It also does not mean that such maps cater for all circumstances, but they do contain some principles and an orientation regarding how to respond to and interpret certain situations. Whereas knowledge is something that people carry in their minds, behaviour is directly observable. And it is knowledge and information that underlie behaviour. By referring to the fact that culture consists of the shared information in people’s minds and their behaviour, we acknowledge that it includes mental as well as behavioural phenomena. Furthermore, we acknowledge that the knowledge of one cultural group can be distinct from the knowledge of other groups and this enables group members to behave in a way that is meaningful to them and acceptable to other group members.

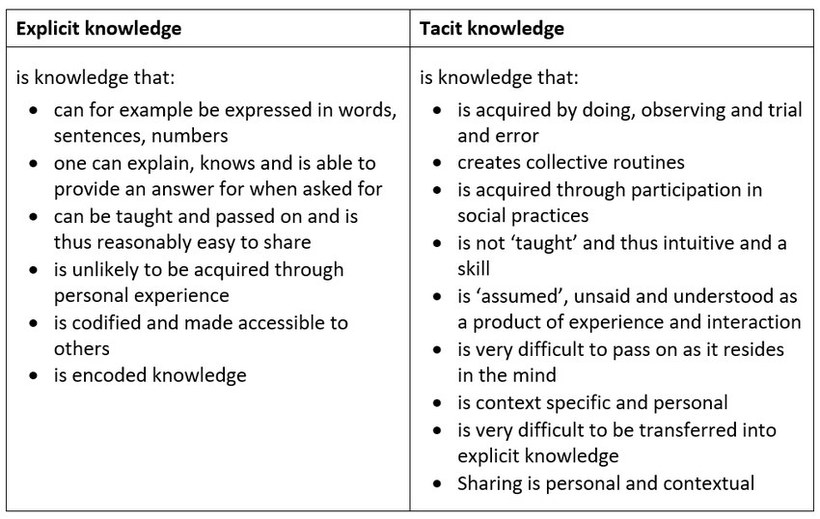

Knowledge which is reasonably easy to articulate, capture, store and retrieve is called explicit knowledge. For example, if you start working for a company, you are likely to be given a booklet containing information about the history, organisational structure and a guideline of what is expected from you when working for the company. We can find explicit knowledge, for example, within a company's help centre, knowledge bases, process documentation, user guides, white papers, research reports, data sheets, specifications, organisational charts, formal documentation, as well as video and audio recordings.

Spain represents another example. The fact that Madrid is the country’s capital is well known and also that Spanish is the officially recognised language of the country. It is knowledge which can easily be gained, recorded and passed on.

A concept that is much more difficult to grasp is tacit knowledge, which is unconscious and unacknowledged information that is silently acquired through experience, socialisation, and habitual practices. It is unconscious knowledge that, if asked for, would be the most difficult to write down, articulate, or present in a tangible form, or at least it would take a lot of time and effort to articulate it.

Think, for example, about your grandmother’s most delicious cake. Even though she has given you the recipe or has told you all the ingredients you need, when you try it out, you feel as if something is different or missing. The reason is that after years of experience, she has learned the exact feel of the dough, or exactly how long the cake should be in the oven. It’s not something she can write down; she simply feels it.

Understanding culture as common practice, it should be clear that a large part of culture-specific everyday knowledge is tacit knowledge and this is difficult to transform into easily attainable explicit knowledge.

We can observe a further example by thinking of how we learn a language. Learning the alphabet, the sentence structure and vocabulary is the explicit knowledge that we acquire. But pronouncing words like the locals or acquiring an accent specific to a region usually requires the acquisition of tacit knowledge, which may well only occur after we have lived in the region for a while and become immersed in the culture. But having obtained the local accent, are we able to recall how we actually did it? Generating innovative ideas could be another example of tacit knowledge. How do we generate new ideas, new ways of doing things and developing a product? Is it based on intuition?

Task: Culture and knowledge (1)

Please look at the two photographs below. The one on the left shows a footstool at a market in Laos and the one on the right rats pinned to sticks in Mozambique.

Note down in your learning journal the impressions that come to your mind when you see these pictures.

Photograph on the left by Adelheid Iken. Photograph on the right by Yeliz Yildirim-Krannig

Having completed this task, click here to view some associations mentioned by other participants.

Show / hide sample answer

Other participants noted the following:

- I feel disgusted, how can someone eat rats?

- The people must be really poor if they have to eat rats.

- I could never ever do this.

Explanation of the pictures shown:

In Mozambique and Laos some people see rats as food or bush meat and eat rats out of choice. In fact, it is said that wild rats eat berries and grains and therefore provide safe nourishment.

The picture below was taken in New York’s underground. Many would look at the picture with the understanding that rats are unclean, vicious and parasitic animals that steal foods and are spreading diseases. This may be related to the historical memory of the so-called Black Death, one of the most feared diseases in the 14th century which led to the death of several million people in Europe. It was spread via the bite of infected rat fleas. This experience might have led to the believe that rats are especially unclean animals, unfit for consumption.

Source: Photograph by Yeliz Yildirim-Krannig

In the temple of Karni-Mata in India rats are treated well and provided with food as the picture below illustrates. Here people perceive rats as holy animals called kabbas. This belief has its origin in the 14th century and is based on the understanding that rats carry the souls of people who have passed away.

Photograph by Simon from Pixabay, licensed under the Simplified Pixabay License.

Task: Culture and knowledge (2)

Now that you know more about rats, read again what you wrote as a first reaction when you saw the pictures of the rats offered in food stands in Laos and Mozambique. Taking into account the explanations from above, how might they help you to understand others and our own behaviour? Note down your answers in your learning journal.

Having completed this task, click on the following link to view a possible answer.

Show / hide sample answer

Looking at the picture with rats on sticks was really difficult for me, I must say I even found it somewhat repulsive. The thought of people eating that would lead me to ask myself: "Who would want to eat something so dirty, and what does that say about those people?"

However, after I read the related text, I noticed that the people eating those rats could just as well ask me: "What is your problem with eating rats?" After all, they are certainly not more or less dirty than chicken, cows or other animals that I would have no problem eating off a stick. After reading that my behaviour towards rats comes from historical reasons, with rats being seen as spreader of diseases hundreds of years ago, I came to think that it is worth looking into my own judgments, and to find out where they actually come from. That also helps me to understand behaviour that I do not understand right away.

Task: Culture and knowledge (3)

From your experience, think about one example where knowledge in a work or university context helped you to understand different behaviour or signs.

Having completed this task, click on the following link to view a possible answer.

Show / hide sample answer

Linda from Germany did an internship in Shanghai. Working with her Chinese colleagues, she noticed that when they asked her to get something done, they would often repeatedly emphasize how urgent the task was, and ask her days before the agreed deadline whether she could really deliver it on time. She found this rather disturbing since, after all, she had promised to get it done till that day. Her colleagues' reminders would sometimes give her the feeling that they did not think of her as a reliable intern. She would feel even more so when she saw that more often than she was used to, the colleagues themselves would not stick to the deadlines. After she grew somewhat frustrated with this behaviour, she talked with her colleague Xiao Hong about this. She really liked Xiao Hong, and saw her more as a friend than as a colleague.

Xiao Hong explained to her: "I can see that you are frustrated because you think our colleagues do not think you are reliable. But that is really not the case. You see, in our industry, things just constantly change. Deadlines that we agreed on can be quickly obsolete, because the customer does not need something anymore, or our boss changes her opinion. This is why we feel the need of constantly reminding our colleagues that the task is indeed still important. This is also why when you do not remind our colleagues of the urgency once in a while, they might sometimes think that the task might not be so important anymore. This is especially the case when our customers or bosses suddenly give them something urgent to do, which happens very often here."

This information really helped Linda to understand the behaviour of her colleagues and to make her less frustrated. She now realised that this was not something she should have taken personally.