When we talk about social behaviour, we refer to the way in which people within and between collectives interact and how they relate to each other. Social behaviour therefore describes the general conduct exhibited by individuals within a collective. When a child learns to ‘behave’ and act in a way which is considered appropriate by their environment, they acquire culture, a learning process which continues throughout life. Being socialised into a community or collective usually means having and sharing deep-rooted beliefs, values and assumptions, most of which are taken for granted and unconscious.

Let us consider eating habits for example. At some point in time, specific behavioural patterns started to be considered appropriate by most members of the collective and as such these became part of normative behaviour. This explains why members of societies in which food is commonly eaten with a knife and fork consider this to be normal and appropriate. As a consequence, they are likely to view other eating habits with disdain or even disgust and may for example consider belching as completely inappropriate. They do so because in their communities different eating habits are deemed appropriate and well-mannered. The way we behave and what we consider to be ‘good’ behaviour is thus not naturally given, but developed in response to both the environment and the available resources. These are passed on to the next generation as ‘proper behaviour’ and as part of our culture.

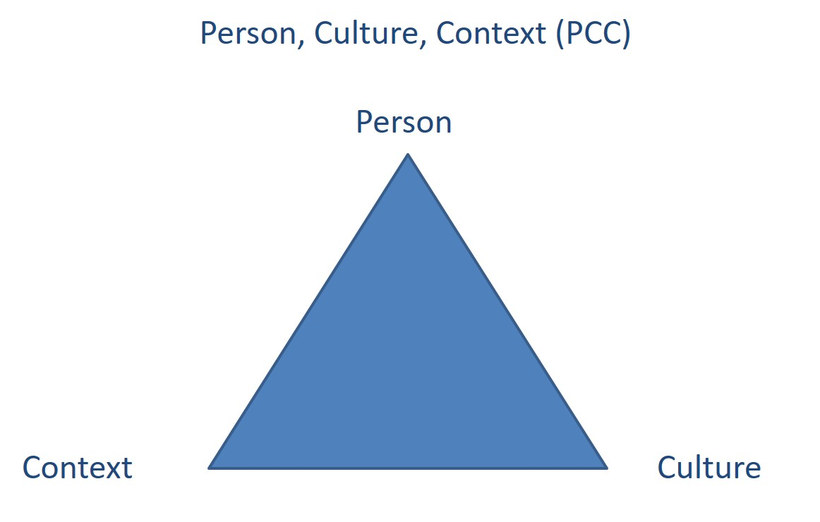

When interacting with others, there are, however, two other components which influence social behaviour. These are the characteristics and personality of the actor or actors and the situation or context which governs the interaction. This means that despite a person's propensity to behave in a certain way, their behaviour may change depending on circumstances. For example, we might have a preference for direct communication due to our cultural upbringing, preferring to clearly spell out what we want. However, in specific circumstances, for example when we want to ask somebody for a favour, we may deliberately or intuitively revert to a more indirect communication style.

Generally speaking, social behaviour is acquired and learned through observation and interaction. It can be viewed as a socially perceived routine and expected sequence of actions, or an understanding of how things should be done.

Let us start exploring the link between culture and social behaviour by analysing two case studies.

Task: At the doctor

Imagine you need to go to the doctor and are asked to wait in the waiting room to be called upon. In the waiting room, there are many chairs and there is only one other patient. Where would you choose to sit? Selecting from the list of available options below, which you will also find in your learning journal, tick the one or the ones you consider to be relevant and note down why you have chosen this particular seat.

- You choose to leave at least three chairs in between you and the other patient in order to avoid any infections

- You want to sit far enough away so that the likelihood that the other patient talks to you is minimised

- You want to sit close to the window and are not concerned about the other patient

- The other patient looks to you like a very empathic person and you choose to sit within ‘talking distance’

- You don’t want to sit at the other end of the room because the other patient may feel intimidated if you choose the furthest seat from her

- You want to sit next to the door so that you can quickly get up when called upon

- You want to sit very close to the other patient so that you can console her and have a good chat

- Another option...

Whatever seat you choose depends on a variety of factors which include person, culture and context (PCC). You may be a person who is very communicative and likes to get to know other people, i.e. your personality would be involved here. On the other hand, you may have learned that sitting next to a stranger in an otherwise empty room may be perceived as an intimidating and uncomfortable experience and inappropriate. This thought relates to culture. Last but not least, the context in which the interaction occurred plays a role. Your choice might have been different, for example, if you had been waiting at an embassy in order to obtain a visa for a country you would like to visit. In this case you would have hoped to gain some helpful information from the other person in the room. The context, therefore would have informed your decision.

We don’t usually spend time thinking about where to sit in a waiting room and even less so how culture influences our choice. However, this experiment serves to make us more aware of how the aspects of culture, person and situation govern our behaviour. And this, in turn, is an important stepping stone towards dealing with behavioural differences. So let us look at another example:

Task: The missing information

You are working on a project with four others and have been asked to prepare a presentation of your results. The deadline is tight and when you realise that you need information from your colleague Huan, one of the team members, you are not too sure what to do because Huan is out of the office for the afternoon and cannot be reached. However, you know that the file with the information must be on his desk. What do you do? In your learning journal, tick one of the three options.

- You know that the documents must be either on Huan's desk or in his filing cabinet, so you walk over to his desk and search for the information you need.

- You walk over to Huan's desk and see whether the file with the information is visible, but feel reluctant to actively search for it.

- You leave a note on Huan's answering machine and wait for his return to the office.

Regardless of the choice you make, you cannot be sure of Huan's reaction. Read through the different possibilities and think about explanations for any of his possible reactions:

- I can’t believe that my colleague actually went through my file and documents. I feel that my privacy has been truly invaded.

- I feel sorry that I couldn’t be reached and am glad that my colleague took the liberty to search for the missing information. I don’t mind my team members doing this, we are in this together.

- Well, I guess that my colleague was under pressure and didn’t really know what to do. But going through my filing cabinet and documents has left me with an unpleasant feeling of 'invasion of privacy'.

Again, when looking back at the situation and analysing it, we need to consider: Person, Culture, Context (PCC). On the cultural level, we can draw a distinction between people who have a strong feeling about what is private and what is public. In our case Huan may be a person who feels a strong sense of ownership regarding the information he holds and therefore perceives the act of searching through his documents as an invasion of privacy. Other people may be less concerned and feel that because they are a team, information should be shared without any fuss and if that means searching for it, then that is fine. So, how you generally perceive what is private and what is public is also related to culture and how you have been socialised.

The PCC model

The PCC model reminds us that culture is not the only aspect which influences behaviour. As Barmeyer and Haupt (2007) argue (and the PCC model indicates,) other factors that require consideration are the characteristics of the actors involved and the context in which the situation is embedded. For example, when considering the person or persons involved, we need to think about their position and function, their personality, their way of communicating, their ability to adjust, their experience, and their openness to difference, to name but a few. The factor situation includes aspects such as the physical context, power relations, the organisational structure, the organisational processes, the competitive situation, and the project constellation.

As we have already mentioned, there is an immense variation in social behaviour in and across societies and collectives. Considerable research has been carried out to analyse and compare the different ways people interact and relate with each other. Probably the best known researchers in this field are Geert Hofstede et al. (2010 Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, revised and expanded 3rd edition, New York: McGraw-Hill), Fons Trompenaars & Charles Hampden-Turner (1998 Riding the waves of culture; New York: McGraw-Hill) as well as Edward T. Hall (1959 The silent language; New York: Doubleday; 1966 The hidden dimension, New York: Doubleday).

What these researchers have in common is the search for features or dimensions which can help us to analyse a society and compare it with others. Their conceptualisation of differences centers on values, arguing that a society socialises its members into distinct value priorities. Individuals are then driven by this value orientation to behave in a way which is compatible with the values they have internalised.

In doing so, Geert Hofstede, for example, scores countries on several value dimensions. However, many researchers have criticised his work because using country level scores assumes that the average values are broadly representative of the entire country, which is questionable. Another critique relates to the generalisation of cultural patterns regardless of the specific situation. Finally, Hofstede assumes that value orientations remain fairly stable at the micro- and macro-level. Yet, there is enough evidence showing drastic behavioural changes within societies, e.g. due to digitalisation and technological advances.

One way of acknowledging this critique and at the same time benefiting from their work is by considering individuals and their orientations, thereby using cultural dimensions as a general framework to understand in which ways people’s behaviour may differ and how we perceive our own general behavioural orientation. In this way we are not considering country and country level scores. The following dimensions have been chosen because they provide us with a good orientation of the different ways people may relate to each other in a work context. The six dimensions are:

- task versus relationship

- independent versus interdependent

- egalitarian versus status orientation

- direct versus indirect communication

- risk versus certainty

- monochronicity versus polychronicity

Following Lane et al. (2019) and the approach of mapping cultural and other differences between people who meet and want to work together, we will introduce and explain the six dimensions and use them as a basis for mapping and thus developing a personal cultural profile.