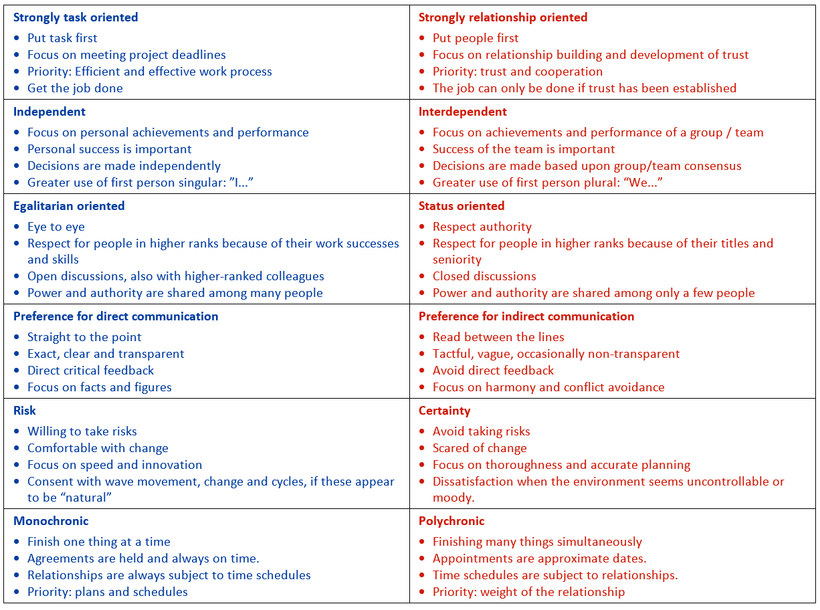

An important element in mapping investigates the question of how we want to work together. Lane et al. (2019) introduce five cultural dimensions, developed in conjunction with GlobeSmart, which they consider to offer a good combination of validity and practical relevance. These are: Task versus relationship, independence versus interdependence, egalitarian versus status, directness versus indirectness and risk versus certainty. The dimension of time was added in this context because it plays such a vital role in a business context.

If we use these six dimensions to map our cultural profile, then we are encouraged to acknowledge individual orientations and also the image people have of us in a specific context. Mapping occurs by locating each individual between a high and low orientation on each scale. This, of course, can never provide a completely accurate reflection of a person’s behaviour. One reason for this is that when we place ourselves on a scale, we necessarily implement our own unique understanding of the particular concept. I may or may not share some of this understanding with others. Nevertheless, it does provide us with a basic orientation.

First, we will examine the cultural dimension task versus relationship. This dimension refers to the fact that people who work together must complete a particular task, while at the same time taking care of relationships with their team members. In any team there are likely to be people who primarily want to focus on the task and the production of results. Consequently, these people will place a lot of emphasis on goal setting and planning. There may be others, however, who consider it vital to establish good relations with their work colleagues before and while performing the task at hand. These team members will be focused on interactions and fostering positive relations as well as taking care of the well-being of their colleagues.

Task: My fellow researchers

Read the case study and find indicators which may suggest that Vadim is more relationship-oriented than his fellow post-graduates. What could be other reasons as to why Vadim’s colleagues are so reluctant to talk about private issues? When answering this question think about the context as well as personal issues. Where might Vadim be making assumptions? Note down the answers in your learning journal.

Vadim is a post graduate student of Mechanical Engineering. A couple of months ago, he joined a research group, and now shares an office with two local post-graduate students. Overall, he likes it very much, and his colleagues are very nice, but he finds it difficult to establish personal relationships with his local co-workers. Even after several months, nothing has changed. He has barely found out anything about their family lives, and when he asks them about their personal lives, the response is usually short and seems rather distant to him. His co-workers just don’t seem very interested in him. And even though he’s been a member of the group for a long time now, so far he has not received a single private invitation. Now he is wondering what he might be doing wrong and comes to the conclusion that apparently his fellow researchers are naturally cold.

Source: Translated and adapted from the research project "Mehrsprachigkeit und Multikulturalität im Studium" (Multilingualism and multiculturalism in studies / higher education, MuMis project, 2011)

Both relationship and task-focused people are usually committed to completing the task and get the work done. However, their way to achieve this goal may be quite different. Task-oriented people tend to get started with their work quickly and consider relationship-building to be something which may develop as work progresses. They are likely to be the ones who develop a step by step plan and concentrate on meeting deadlines and achieving milestones. They are interested in task efficiency. For relationship-oriented people it is important to familiarise themselves with the people they are working with, and this is likely to include getting to know them more personally. Building good relationships first not only shows them whether the person is trustworthy but also lays the groundwork for good communication. Socialising is therefore an important part of work, which might involve drinking tea or coffee or eating together. It may even mean that part of the task is completed outside the office and office hours, for example during dinner or over a drink. Relationship-oriented people are likely to view a good relationship with co-workers and a positive work atmosphere as vital to achieving the necessary results.

Task: Getting to know each other

Read the case study and in your learning journal note down the answers to the following questions:

- Which topics does Karen consider to be inappropriate?

- What could be reasons why Thao is asking these questions?

- Which topics would you consider to be inappropriate in this context?

At the beginning of a two day workshop at a German university, participants are asked to get to know each other. To this end, participants meet in pairs. Their task is to introduce each other and share personal information. Karen meets Thao, an international student from Vietnam. When she introduces herself, Karen touches on fairly general issues related to her studies, travel and hobbies. Thao, however, is interested in knowing more about her career and financial plans, and asks whether she is married and what her financial background is. Karen considers these questions to be very personal and decides to give only very vague answers. She is glad when this ‘getting to know each other’ activity is over and decides to keep her distance from Thao.

Source: Based on a critical incident from the MuMis-Project 2010, C05; http://www.mumis-projekt.de/mumis/index.php/ci-datenbank/situationen-typen/c-kommunikation-in-arbeitsgruppen/c1-gruppenarbeit-im-rahmen-von-lehrveranstaltungen, accessed on 19.11.2020

The second dimension, independent versus interdependent, refers to the preference of working on our own versus coordinating with and helping each other with tasks. Independent entails giving more emphasis to the pursuit of our own ideas and personal goals and staying in control of events. In contrast, interdependent people share an understanding that the task can only be accomplished through mutual reliance. These people are highly responsive to the needs and expectations of others as well as being ready to support the people you are working with. In order to achieve this, a positive working atmosphere is vital, as well as a sense of loyalty and duty towards others.

This shows that colleagues who value interdependence and independence are likely to approach working together very differently. Interdependently oriented colleagues, for example, are likely to require frequent interaction, assign roles as necessary and are quite flexible in their approach, whereas independently oriented colleagues are likely to be confident working on their own and subsequently reporting back to others when a scheduled task has been completed. For them it is important that roles, once assigned, remain constant and that rescheduling and flexibility is kept to a minimum.

Interactions are important for both independently and interdependently oriented people alike. However, the extent to which they value collective effort differs and this will influence their assumptions with regard to the best way to work together.

Task: Working together?

Read through the case study and indicate why Mihai and his fellow student may have different understandings of ‘carrying out a team task’. Note down the answer in your learning journal.

Mihai is expected to join two other students and carry out a team task. Together they are expected to work on a difficult text and use it as a basis for answering a couple of questions. Mihai is very quick in working through the text and answering the questions. In no time he is ready to share his results with the other team members. He is perplexed and upset when he realises that one of his fellow students is quite annoyed about his approach. All he wanted to do is help!

Source: Based on a critical incident from the MuMis-Project 2010, C03; http://www.mumis-projekt.de/mumis/index.php/ci-datenbank/situationen-typen/c-kommunikation-in-arbeitsgruppen/c1-gruppenarbeit-im-rahmen-von-lehrveranstaltungen, accessed on 19.11.2020

The third dimension, egalitarianism versus status, refers to how power and responsibilities are allocated and distributed. An egalitarian-oriented colleague is one who believes that all are more or less equal and power and responsibilities should therefore be shared as evenly as possible. The assumption is then that issues should be discussed and decided upon together and that everyone is expected to contribute towards the task at hand. Organisations who have an egalitarian-orientation have flat hierarchies, which means that employees generally have a great deal of independence and are allowed to make high level decisions. The objective of this kind of environment is to maximise employee motivation and commitment, thereby bringing out the best in everyone.

In more hierarchy and status-oriented work environments, people tend to expect that decisions will be made by superiors. Subordinates show engagement inasmuch as they follow instructions and do not necessarily make suggestions or provide relevant information. Power and responsibility are distributed vertically rather than horizontally and subordinates often find it difficult to approach their superiors when problems arise.

Status and hierarchy-oriented people tend to value formal forms of address and titles when communicating. They also tend to emphasise protocol, such as where people sit at a meeting, in which order they speak and how a meeting is run. Highly status-oriented people are also likely to have privileges such as larger and better equipped offices, membership cards or reserved parking lots. In contrast, egalitarian-oriented people are more likely to use and expect first names, speak and interact with the boss in a similar way as one would with a peer. They would also assume that people should receive the same benefits. In this way of thinking, for example, parking spaces would be allocated randomly.

Task: Hierarchical versus egalitarian orientation

Bowing in Japan is part of a long-standing cultural tradition. Use the internet to search the for reasons why people bow, how people bow and when they do so. Note down in your learning journal those aspects which relate to status and hierarchical orientations.

The following short case illustrates the unease of an international student who is invited for a cup of coffee by her professor.

Task: A cup of coffee with my professor

Read the short case and think about how you would have felt as a student in that situation.

Today when I went to the cafeteria, I met my economics professor who was next in line. He greeted me in a very friendly manner and invited me to sit down with him and have a cup of coffee. He said he wanted to learn more about the economic system in my country and that he would really enjoy talking to me. I apologised and told him that I could not stay. But the truth is that I feel awkward about this situation, after all, he is my professor.

The excerpt from an internship report indicates how power distance can influence work processes and be perceived by someone who is not used to a hierarchical system.

"My boss tells me exactly how I have to do my work without allowing me to question or influence his decisions. It therefore sometimes seems to me like I am being controlled. For instance, I had to create an excel-sheet, whose formatting I had to revise approximately ten times before it was suitable. This is new and unfamiliar to me, owing to the fact that I have previously worked for superiors who wanted me to be self-reliant and work independently."

The fourth dimension, directness versus indirectness, relates to a team member’s communication style. Somebody who values a direct communication style has a preference for frank, concise and straightforward communication. The aim is to be as clear as possible, leaving very little room for interpretations and ambiguity, thus ensuring communication that saves time. This is also the case when addressing difficult or critical issues, e.g. when giving feedback or finding errors in work submitted. Direct communication is based on the understanding that the person and the message can be separated. This avoids embarrassing people and threatening their face. Short and precise messages are typical for this kind of communication style, as well as written minutes of meetings and detailed instructions, with little attention to non-verbal cues and reading between the lines.

Task: What you think and what you say

Imagine you are in a foreign country and are offered some food, which to you really looks disgusting. You certainly want to decline the offer, but what would you do or say? Choose an option from the list below in your learning journal.

- "This food really looks different and I am sorry, but I cannot eat it."

- "Thank you very much for your offer, I very much appreciate it. But I am very sorry to say that I won’t be able to stay."

- "This food looks disgusting, no way can I eat this!"

- "That is very kind of you, but I am afraid that I am not feeling well."

- "This food looks very interesting and I wish I could join you, but I am afraid I have a stomach disorder."

- Other: ...

People who have a preference for indirect speech use different ways to express the message and tend to communicate in a way that leaves room for interpretation. Pauses, silence, tone of voice, and body language are important parts of overall communication. When communicating the focus is on the receiver of the message and the understanding that other people may have different views of the subject. It acknowledges that everybody operates within a certain context and that reading between the lines might open up avenues for exploring common ground and points of view without pinpointing. In this way embarrassment is avoided.

The fifth dimension, risk versus certainty, relates to the amount od information that is needed before acting. Of course everybody plans his or her actions, but how many details do they require and how much room are they able to leave for unforeseeable and unpredictable circumstances. Risk-oriented team members value quick actions and are ready to go ahead on the basis of information that only provides them with a rough orientation. They trust that by being flexible and by monitoring the process and being flexible they will be able to make the necessary adjustments as they go along. They are therefore fairly tolerant to change and do not consider rules and regulations to be of paramount importance.

The following example illustrates how this difference may surface in behaviour:

Robert is an engineer who is due to hold a presentation for an international group of colleagues. He spends a lot of time and effort working on his presentation because he wants to give his colleagues all the technical details of the new software necessary for them to implement it. After about an hour into his presentation, Jenny raises her hand, and points out: “Richard, many thanks for your presentation, but it is possible that you could just tell us what time it is rather than explaining to us how the whole clock works?”

For certainty-oriented people, giving and receiving detailed information is crucial order to ensure that everyone is prepared for all possible scenarios. However, for risk-oriented people, this can seem much too detailed as they would prefer to simply learn from experience and make adjustments when necessary.

People who have a preference for avoiding uncertainty require a thorough and detailed stock of information as well as a detailed plan before they feel comfortable committing themselves. This might include an intensive and detailed analysis of the issues at stake considering different aspects and points of views in order to avoid possible risks and eventualities. During the implementation phase the focus then switches to staying on track and following the agreed plan rather than adjusting it ad hoc. Having a detailed and agreed plan is perceived as creating transparency for all stakeholders. Milestones are understood as anchors that help to visualise the progress of the project and rules and regulations make it clear which actions are expected from everyone involved.

Task: A team presentation

Read the case study and in your learning journal note down how Alice might explain to Ajul why she finds it difficult to follow his way of approaching the team task.

Alice is a member of a working group of three that is supposed to give a presentation in a few weeks as part of the course requirements. On the initiative of her fellow student, Ajul, they developed a detailed schedule and tasks were allocated to the different members of the group. At the following meeting it turned out that nobody apart from Ajul had followed the plan and schedule. In addition, the other students got lost in discussions about things that were not directly linked to the actual task. This really annoyed Ajul, who kept asking them to stick to the plan and even accused Alice and the other student of being undisciplined and lazy. Thinking back to the work group meeting, Allice realised that for her, it is good to have a plan but this does not mean that it has to be followed meticulously and that it would be helpful to reach an agreement as to how they want to approach their task.

The last dimension is the monochronic versus polychronic notion of time. This influence of this dimension on teamwork is often underestimated. Indeed, especially in the light of the increasing urgency and time pressure that organisations and societies feel, the fact that people may experience time differently has a crucial impact on the flow and coordination of work and how we can best work together.

The following quote from a learning journal indicates a rather time conscious and structured working style.

"It bothers me when I run out of time, that’s why I like to start immediately after getting the task. Especially when we started our teamwork, one of my major personal needs was to clarify which member is responsible for keeping our timetable and work efforts updated so that we all have a kind of a structure which displays our progress and helps us to reach the goal. My personal preference of getting things done immediately and in the best case, being ready at least a few days prior to handing in the task also effects my course of action."

Source: Learning journal, 2020

Within our relationship to time, an important differentiation can be made between monochronic and polychronic time orientations. This refers to whether we feel comfortable multi-tasking, i.e. juggling several things at once or whether we rather have a tendency to schedule our tasks sequentially, accomplishing one task after another. The following is a good illustration of the difference between a monochronic and polychronic working style.

The work of a hairdresser illustrates the polychronic orientation nicely. Especially in smaller salons, hairdressers need to maximise their time. This is why they are likely to attend to several clients at once. One might be having their hair coloured, while another sits under the dryer or is asked to go to the shampoo basin. In between, the hairdresser takes phone calls and makes appointments. A mail courier, on the other hand, needs to behave quite differently, completing one transaction before moving on the next one, since most of his tasks cannot be intermeshed.

Source: cf. Ballard, D. I., & Seibold, D. R. (2003). Communicating and organizing in time. Management Communication Quarterly, 16 (3), p. 387.

The quote also indicates that in addition to the cultural element of monochronic and polychronic time orientations, they can also simply apply to different work contexts.

Task: Business deal

Read through the following case study and in your learning journal note down how the concept of monochronicity and polychroncity can help us to understand Mr. Balto’s and Mr. Bau’s behavioural expectations.

Mr. Baus, an experienced businessman, was sent abroad to negotiate on behalf of his company with a potential sales partner. As agreed, Mr. Baus arrived punctually at his negotiation partner's office at 11:30 am. However, Mr. Balto does not appear until approximately 11:45. He greets Mr. Baus extremely cordially, but does not seem to consider it necessary to apologise for his tardiness. In addition, he seems to make no effort to ensure an undisturbed atmosphere for their discussion. Despite Mr. Baus's presence, he repeatedly makes brief telephone calls and allows himself to be interrupted by colleagues. After an hour, Mr. Balto invites him for lunch and Mr. Baus therefore thinks that now, finally he will have an opportunity to discuss business matters with him. However, even here, Mr. Balto becomes involved in countless conversations. He chats not only with business partners, who all make themselves comfortable at their table, but also with friends who he meets by coincidence. Full of enthusiasm, he introduces each one to Mr. Baus, who becomes increasingly impatient

Source: Based on Zaninelli, S. M. (2005). Six-Stage-Model of an intercultural "Integrative Training Programm", http://www.culture-contact.com/resources/2017-von-Ulrike-Reisach-IKT-Six-stage-model_Culture-contact-Artikel.pdf, accessed on 30.11.2020

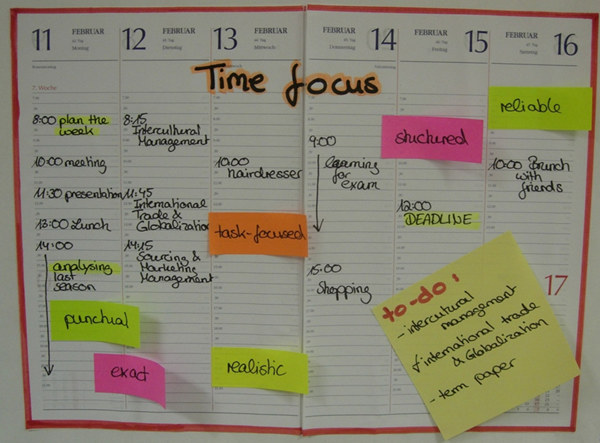

Another aspect of time could be seen as the notion of event versus clock time. The 'event time orientation' views time as cyclical and a continuous flow, where tasks are planned relative to other tasks and activities take place in succession from the past to the present and into the future. This means that you ‘call it a day’ not at a specific time but when the work you felt needed to be completed is actually finished. Clock time in contrast works according to precise schedules and activities anchored to time slots. This also means that days, for example, might be compartmentalised into when they begin, what happens after breakfast at a certain time etc., as the picture below indicates.

Photograph by Adelheid Iken

Closely linked to time orientation is the question of flexibility with regard to work schedules as well as our understanding of punctuality and deadlines. This is highlighted by the following case study.

Task: Differences in time orientation

The following short case illustrates different time orientations. Read the case study and in your learning journal note down two positive aspects relating to clock time and two positive aspects about with regard to flow time.

Mr. Miller was the chairman at an international meeting and had asked the group to reconvene at 2.00 pm precisely, since they had a tight agenda for the afternoon.

At 1.50 p.m. most participants had returned to the meeting room and were chatting. At 2.10 pm Mr. Miller started to become restless and impatient, waiting for the last participants to return. Two participants were still in the corridor making telephone calls. They came in at 2.20 p.m., which encouraged Mr. Miller to say in a somewhat irritated voice: “Now, ladies and gentlemen, can we finally start the meeting.” When he said this and looked around, Mr. Miller noticed that some of the participants looked a puzzled and dismayed by the tone of his voice.

Task: Opening hours

Look at the photograph below and consider what time you think the shop will reopen. What would somebody who is used to clearly defined opening hours think about the shop owner?

Photograph by Adelheid Iken

Using cultural dimensions as a framework can support our understanding of possible behavioural differences. They can also help us to understand which type of behaviour we display and expect when working with others, and this insight promotes self-awareness. It also helps us to see differences in behaviour from other perspectives.

Task: Getting to know myself and my cultural orientation

Knowing yourself is a crucial stepping stone in the direction of behaving effectively in an intercultural setting. The dimensions discussed here can be helpful in achieving this self-insight. Read the questions and, assuming a work context, use the scales in your learning journal to position yourself between one and five.

Click on the image for a larger view