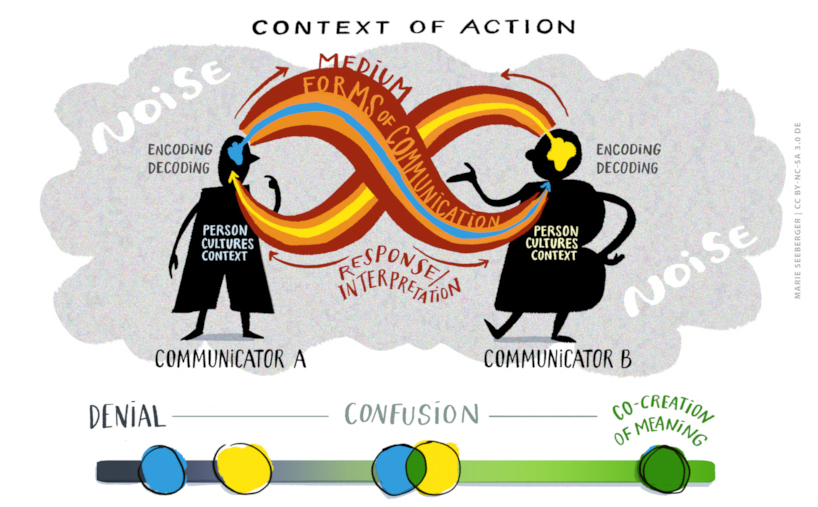

As stated earlier, we have isolated the various components of the communication process here for analytical purposes. In practice, of course, they occur almost simultaneously as the communication process evolves. In the next step we will observe how the different elements of the communication process relate and interact with each other on a graphic. Although pictures or communication models such as the one below offer a somewhat simplified perspective, they nevertheless help us to grasp the complexity of communication.

The transactional model was chosen here because it focuses on sharing, participating, and bringing people together with the goal of co-creating meaning, thus building a community through the communication process. It is the “we”-orientation that contributes to the creation of an atmosphere in which we feel understood, supported, and respected.

The transactional model of communication (part 1)

Source: Based on and inspired by Bosse, Elke (2011, p. 103)

Image by Marie Seeberger (www.behance.net/marieseeberger) CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 license

Click on the image for a larger view

The transactional model, originally developed by Dean Barnlund in the 1970s, takes the ideas of Shannon, Weaver and Schramm one step further by showing that the sender and receiver are simultaneously and reciprocally engaged in sending and receiving information. This is why in our model they are not referred to as sender and receiver but as communicator A and communicator B. We have depicted the reciprocity and simultaneity as a kind of Möbius strip that cannot be orientated and in which it is impossible to distinguish between clockwise from counterclockwise turns on its surface. The simultaneity and reciprocity also apply to the reactions, feedback, and interpretations of the communicators as well as the process of coding and decoding. This also indicates that both the form of communication and the medium are not fixed and can change during the communication process. The sources of interference are depicted here as a cloud, as they can be effective throughout the entire process. And, as already mentioned several times, it is important to consider the context of action, which influences the entire communication process.

The goal of communication is the co-construction of meaning, but, as the model also shows, this can never be fully achieved, and we can therefore only ever get as close to the goal as possible. This also has to do with the fact that we contribute and influence the communication with our person, our cultural imprints, and our very specific situation and thus the individual context from which we communicate. It is also possible that confusion, incomprehension, or irritation can arise in the communication process, which can be partially or completely resolved in the process or result in various forms of rejection. We will look at these reactions and how to deal with them in the communication process in the next learning unit.

The model also indirectly shows that communication has a relationship component and a content component. While the content refers to the information on the topic of the communication, the relationship component refers to how the communicators understand their relationship with each other and how it develops. So, we communicate to exchange messages and information, and at the same time we communicate to create and maintain relationships, form alliances, and engage in social interactions with others. Through this process, we contribute to the construction of social realities.

The transactional model was chosen here because it focuses on sharing, participating, and bringing people together with the aim of co-creating meaning and thus building community through the communication process. It is the ‘we’ orientation that helps to create an atmosphere in which we feel understood, supported, and respected.

Task: The internal audit

Analyse the communication situation below based on the transactional model. Using your results, argue to what extent Marino and the department manager were able to co-create meaning. Note down your answers in your learning journal.

The background:

Marino is an internal auditor. His current assignment is to audit a company’s travel department. The travel department is responsible for organising and paying for all the travel and accommodation arrangements as well as arranging visas for a staff of 35 international executives and sales representatives.

The communication situation:

Marino arrived at the travel department at the arranged time but was kept waiting in an auxiliary office for nearly 25 minutes. When he entered, he looked somewhat obviously at his watch. The department manager gave him a broad smile, saying: “Ah, we have plenty of time, have we not? Would you care for a coffee?” Marino politely refused.

The manager, having shaken hands with Marino, moved a bit closer, upon which Marino felt uncomfortable and backed away.

Marino’s discomfort was increased by the fact that the office seemed overcrowded, with desks occupied by people to whom he had not been introduced, while other people continuously came and went through a side door.

The conversation was interrupted several times by various people who asked the manager questions. The manager replied, while interspersing his replies with remarks directed at Marino, who began to feel increasingly confused.

After they had sat down and exchanged pleasantries, Marino began by raising the two problem areas that were highlighted in the preliminary audit report. One referred to complaints about late payment of travel expenses by expatriates working in the subsidiary. The other concerned numerous instances where rules had been infringed upon.

He suggested dealing with them in that order and the travel manager agreed, but then jumped straight to the rule infringement question.

“You know, some of those rules are really not practical”, he said. “They just make extra work for no reason. I take it you agree that your colleague found no instances of dishonesty or misappropriation of funds?”

Marino agreed – none had been found – but thought to himself: “Rules are rules, and they are there for a purpose.”

Source: Guirdham, M., & Guirdham, O., 2017, p. 145f., amended