We have argued that to grasp the complexity of culture, it's essential to move beyond categories like shared passport identity. For instance, we should consider factors such as age, gender, locality, lifestyle, language, education, and profession as potential markers of both difference and similarity in social life. In essence, if our aim is to discover common ground, it is more advantageous to focus on multi-collectivity rather than nationality, emphasizing a "zoom in" approach over "zooming out." This same principle applies to communicative practices.

As members of numerous distinct collectives, we are accustomed to a variety of linguistic and communicative routines present within these groups. This encompasses what to say, how to express ideas, and when to communicate them. Furthermore, we can argue that we construct collectives through communication. Simultaneously, the utilization of a specific language or communicative practices can serve as an indication of membership in a speech community.

To illustrate this concept, let's look at Mongolia, an East Asian country. According to Robert I. Binnick (2022), Mongolian languages belong to the Altaic language group and are spoken not only within Mongolia but also in neighbouring regions of east-central Asia. A widely accepted, though not universally undisputed, classification distinguishes between the western language groups, which include the closely related Oirat spoken in Mongolia and the Xinjiang region of China, as well as Kalmyk in southwestern Russia, and the eastern group, comprising the closely related Buryat (Russia) and Mongol (Mongolia and China) languages.

This example illustrates that there isn't necessarily linguistic conformity within a country, even regarding the official language(s) spoken. Communities that share the same language can exist both inside and outside a country's borders.

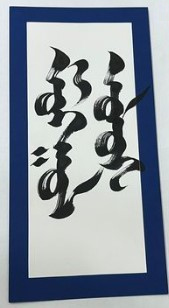

One distinctive aspect of Mongolia is its script, which is written in vertical lines, top-down and left to right across the page, as depicted in the image below.

Figure: Verse written in the Mongolian script, author unknown

Today, alphabets based on this unique classical vertical script are still in use, although the Russian Cyrillic script has become more prevalent in Mongolia. Regarding spoken languages, Russian is the most commonly used foreign language, followed by English, which is gradually gaining in popularity. Additionally, due to the significant number of Mongolians working in South Korea, Korean has also seen an increase in usage (cf. Mongolian script - Wikipedia, January 16, 2023).

Examining the scripts, languages, and dialects spoken within Mongolia showcases the linguistic richness present in the country. The fact that many individuals can converse in multiple languages highlights the presence of various, sometimes overlapping, speech communities. This diversity is further enriched by young people in Mongolia who seamlessly blend and mix languages in their daily interactions, both online and offline. In this context, Dovchin (2016; p.1) even refers to a generational gap in modern Mongolian communication. One of her interviewees, Bolor, supports this observation, noting that at times, she must explain her way of speaking to her parents and grandparents because they struggle to understand what she considers a completely normal form of communication.

A common practice, for instance, involves combining Mongolian suffixes with English stem words. An example of this is the question "cocktaildehuu?" which means "Shall we drink cocktails?" In this instance, the English stem "cocktail" is appended to the Mongolian question suffix "-dehuu?" ("Shall we do something?"). As Dovchin (2016; p.7) asserts, creating new words in this manner is an everyday occurrence.

Another method of incorporating English into the Mongolian language involves using English expressions like "wow," "Hey," "oh," and "ouch" in conversations. Dovchin (2016; p.8) points out that there are hundreds, if not thousands, of Anglicized Mongolian linguistic expressions in youth language. Additionally, it's common to include English verbs in Mongolian, such as saying "chatlah" meaning "to chat," "emaildeh" meaning "to email," or "showday" in the sense of "to go out" (Dovchin (2016; p.8). However, English-oriented resources are not the only ones integrated into everyday communication, as illustrated by the following Facebook entry:

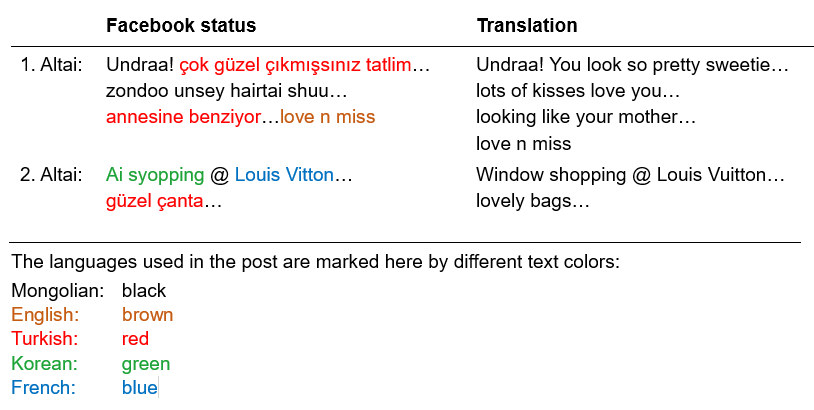

The following figure refers to a Facebook post from an exchange between Altai and Undraa.

Source: Dovchin, Sender (2017, p. 152), modified

In the first line of the exchange, Altai uploads a photo of her friend, Undraa, and comments by blending Turkish and Mongolian language phrases using the Roman script. She also includes the phrase "love n miss," which, according to Dovchin et al. (2018; p. 4), is a popular transnational online expression. The term "Ai Syopping" ("Eye shopping") is a phrase borrowed from Korean English, meaning "I am window shopping," and "Louis Vitton" refers to the well-known French brand, Louis Vuitton. The use of Turkish comes into play because Altai attended a Turkish high school after moving to the capital of Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar (Dovchin 2018; p.4-5). This serves as a typical example of young people amalgamating cultural and linguistic resources available to them, fashioning them into a communication pattern specific to the members of their collective.

These examples highlight that we all belong to speech communities, which can represent larger collectives. Additionally, we are members of smaller collectives that exhibit distinct ways of corresponding and communicating, as exemplified by Altai and Undraa. The written exchange between them also illustrates how deeply social conventions for interaction are intertwined with language and how they are transmitted through language, evolving and changing over time.

Our affiliation with collectives influences the languages we use and how we employ our linguistic resources. Simultaneously, membership in these collectives entails specific social conventions and, consequently, communicative practices that we learn, adapt to, influence, modify, and internalize. These communicative practices typically operate beyond conscious recognition. It is when we engage with individuals unfamiliar with these practices that sharing and understanding meaning can become perplexing and challenging.

Interculturality is understood as a departure from normality, plausibility, and routine actions during an encounter because interlocutors employ different linguistic and behavioural patterns. Consequently, intercultural communication transpires when individuals lack the familiar norms, plausibility, and routines in their mode of communication and, consequently, their communicative acts. Various factors contributing to this can include distinct forms of communication, communication styles, and the use of different communicative practices. These differences can lead to incongruent expectations, misunderstandings, and may result in surprises or negative reactions.

Intercultural communication is thus defined as an interaction during which one or both communicators employ communicative practices that are perceived as distinctive by either party due to their unfamiliarity. This leads to diverse conclusions, assumptions, and interpretations, necessitating the negotiation of meaning and the development of a shared frame of reference.

Task: My speech communities

Identify the language collectives or speech communities to which you belong, and select one of them to showcase linguistic idiosyncrasies that might cause surprises, confusion, or misunderstandings when interacting with people who are not members of your collective. These idiosyncrasies could relate to terminology, specialised vocabulary, a dialect, or specific expressions used within your ingroup conversations.

Note down the results of your analysis in your learning journal.