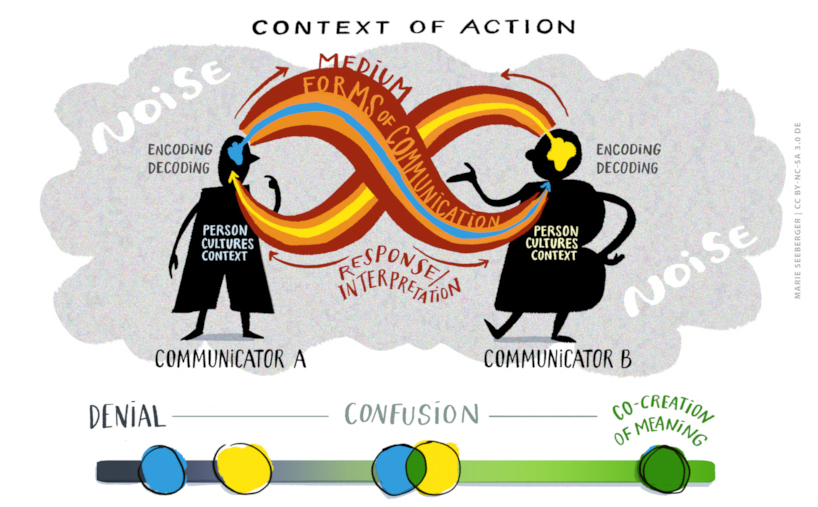

So far, in session 5, we have delved into the communication process and its various components, employing the basic transactional model of communication depicted below.

The transactional model of communication (part 1)

Source: Based on and inspired by Bosse, Elke (2011, p. 103)

Image by Marie Seeberger (www.behance.net/marieseeberger) CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 license

Click on the image for a larger view

We have also gained insight into the roles played by communicators during their interactions. However, it's essential to further explore communicators as active participants in the co-creation of meaning. The next step involves enhancing our understanding of the process by integrating the communicators' cultural and personal backgrounds into our considerations, as well as their situational context, all of which profoundly shape the overall communication process.

Crucially, we must address how to navigate towards the co-creation of meaning when misunderstandings or irritations arise. In this regard, the model illustrates a spectrum of possible reactions. It is worth noting that achieving shared understanding in an intercultural context requires considerable effort. We may also witness varying degrees of confusion within the communication process, as indicated by the continuum spanning from denial to the co-creation of meaning.

Let's initiate our exploration by focusing on the two communicators themselves. Their individual personalities, cultural orientations, and the specific context or situation in which they find themselves all exert significant influence on how they communicate. These factors, in turn, directly impact the outcome of the communication process.

One communicator, for example, may possess a highly inquisitive or adventurous personality, and this aspect of their character significantly influences their preferred communication style. For instance, an inquisitive individual may favour face-to-face communication and engage in asking numerous questions. In contrast, a person with a more cautious personality might lean towards active listening and adopt a more formal approach when responding, as another example. Furthermore, a person's communicative repertoire and established communication patterns are shaped by their individual experiences, background, and education.

In addition, we must consider the individual context or situation in which the communicators find themselves. Here, we draw a distinction between the overarching context of action, e.g., whether it occurs in an office, at a party, or elsewhere (as discussed in Session 5), and the individual context or situation. When we refer to the individual context, we are alluding to the communicator's mood, emotional state, needs, desires, and perceptions of the situation. We are also considering the interpersonal history, the type and depth of relationship the communicators wish to establish, and their feelings towards each other. This is sometimes referred to as the field of experience. Essentially, apart from their cultural orientation, communicators bring with them their personal experiences and history with the other person. When communicators have known each other for an extended period, sharing a long relationship and history, it implies that they have developed a shared experience and may have already established a common communication pattern, familiar with certain reactions and counteractions. This also means that our field of experience has much more overlap when conversing with a close friend than with a new colleague because with a friend, we have already developed a repertoire of common communicative conventions.

Lastly, we must pay attention to cultural orientation, as it influences the communication patterns commonly expected and considered normal, regardless of personal relationships. Every individual possesses a repertoire of communicative practices, which are understood as communication habits developed through membership in various collectives. Members of a collective share a common stock of ideas, signs, symbols, and meanings that are often taken for granted. When communicating, individuals choose from this shared repertoire. Consequently, this shared repertoire influences whether and to what extent communicators perceive themselves to be in an intercultural situation.

For instance, if you've been socialised to view direct eye contact as impolite, you're likely to avoid it yourself, consider it intrusive, and expect the same from your communication partner. However, if your communication partner regards eye contact as a sign of trustworthiness and respect, differences in non-verbal behaviour may lead to confusion and the potential for misunderstandings and misinterpretations. Likewise, attaching different meanings to the same verbal symbols or discrepancies in pronunciation, punctuation, and spelling can significantly impact the communication process. Recognizing one's own communicative repertoire is thus a fundamental step in acknowledging and developing an awareness of potential differences and commonalities. The following test can help you explore this further.

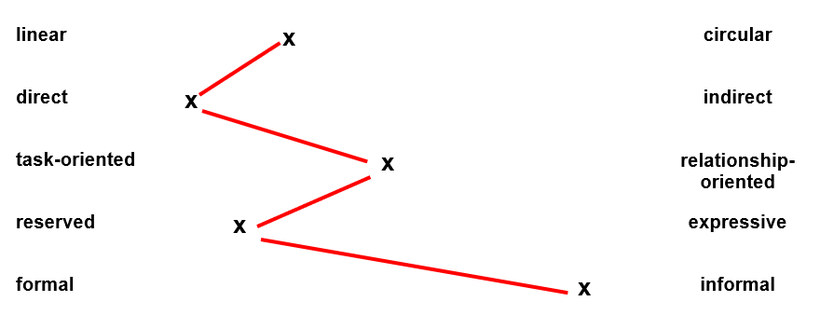

Task: Exploring my communicative resources and preferences

Despite the fact that we adapt our communication style depending on, for example, the context of action we are in, we nonetheless have general preferences with regard to the communication style and we have a specific repertoire of communicative resources. The self-assessment you are asked to do here will provide you with a general idea considering your communicative preferences and resources.

Using the scales provided in your learning journal, please create (a) your personal communication profile and (b) your profile with regard to communicative preferences

Now that you have provided a profile of your communicative style and resources, let us compare it with Luis's profile below, identifying differences and commonalities. In a second step, let's note how these differences and commonalities may affect your communication with others. For instance, if you tend to openly express your emotions while Luis is more restrained, we can explore how this might manifest itself in your communication.

We have the ability to adapt our communication style and approach, often doing so based on the context of the situation. By conducting self-assessments like the one above, we can raise awareness of our own communication preferences as well as those of others, allowing us to identify commonalities and differences. These insights, in turn, can serve as a foundation for the development and discussion of a common understanding.

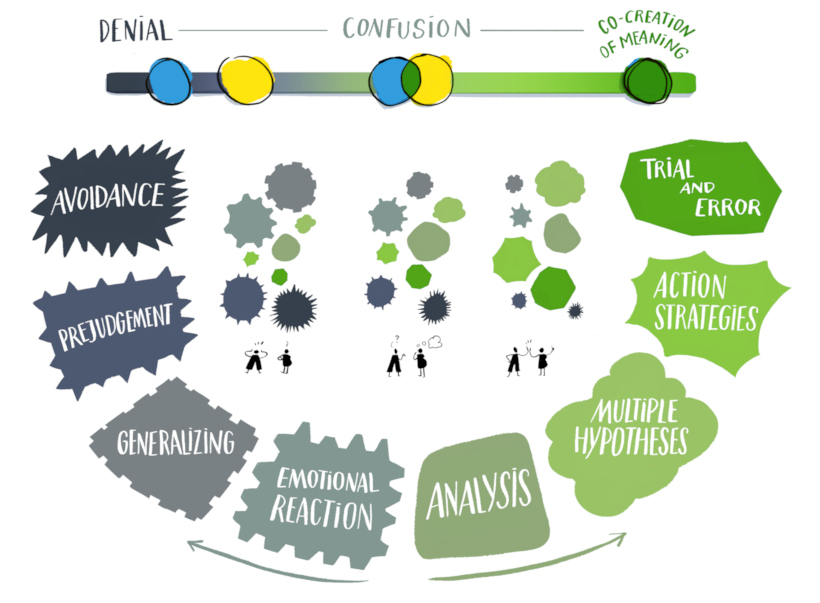

The expanded transactional model of communication

Being aware of one's own communication repertoire and preferences proves invaluable when encountering individuals with differing communication styles. Such self-awareness significantly influences the reactions triggered in these situations. For instance, how do you react when someone makes direct eye contact and employs expressive gestures while speaking? Or how do you respond when someone uses prompts to convey urgency, like saying, "Claude, I need the report ASAP!"

When communication does not align with your expectations, it can elicit feelings of surprise, confusion, or irritation. There may have been instances where a communication breakdown resulted in denial and a refusal to continue the conversation. How did you handle such situations? Were you able to analyse the communication context and consider multiple perspectives before reacting? Were you capable of stepping back, assessing the situation, and seeking a path to co-create meaning, even if it required mending the miscommunication? We will explore these questions by applying the transactional model of communication in its entity.

The expanded transactional model of communication

Source: Based on and inspired by Bosse, Elke (2011, p. 103)

Image by Marie Seeberger (www.behance.net/marieseeberger) CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 license

Click on the image for a larger view

In essence, we view the co-creation of meaning as the outcome of a dynamic process between communicators, emphasizing that communication is inherently interactive. Throughout this process, communicators continually monitor, assess, and respond to each other as the communication unfolds.

However, it's not always clear whether our communication goals have been met or met effectively. This uncertainty can lead to varying degrees of confusion, as illustrated in the model above. In such circumstances, particularly when co-creating meaning appears to have faltered, one communicator might react emotionally, generalize about a collective to which they belong, or choose to avoid further interaction with the other person. Conversely, another individual may embark on a methodical analysis, generating multiple hypotheses and formulating an action strategy to repair the communication and re-establish a co-created understanding illustrated by the bottom part of the model.

As the model depicts it would be incorrect to assume that reactions to communication irritations follow a strict step-by-step process, where one step invariably leads to the next. For instance, a person might become annoyed simply because the other communicator fails to grasp their intended message. While this could potentially result in generalisations or pre-judgments, it's not an automatic progression. In such a situation, one might opt to take a deep breath and then shift towards analysing the ongoing communication process with the goal of finding a solution. Conversely, an individual might have initially developed action strategies and tried them out but subsequently realised that these strategies didn't contribute to the co-creation of meaning. In this case, they may switch to avoidance and decide not to continue the communication.

Now let us delve into a case study to illustrate the possible courses of action and choices following a communication breakdown. Here is the case:

Just a formality?

A female controller has forwarded the half-year figures of the French subsidiary to her colleague at the German parent company. These figures are crucial for the preparation of the group's overall balance sheet.

A few days later, she receives an email from her male colleague in Germany, composed in German:

Sehr geehrte Frau Dupont,

vielen Dank für die Zusendung der Eckdaten. Leider sind die Zahlen, die Sie mir geschickt haben, falsch. Bitte überprüfen Sie diese noch einmal.

Mit freundlichen Grüßen,

Manfred Müller

Dear Ms. Dupont,

thank you very much for sending me the key figures. Unfortunately, the numbers you sent are incorrect. Please review them again.

Yours sincerely,

Manfred Müller"

The controller in France feels confused and somewhat irked. Firstly, she has meticulously reviewed the figures and is rather certain that they are indeed correct. Secondly, the tone of the message from her German colleague strikes her as exceedingly impolite. Consequently, she decides to withhold her response, effectively ignoring her counterpart in Germany. Time passes, and still, there is no response from France. Nevertheless, the imperative task of preparing the consolidated balance sheet remains.

Source: Grosskopf, Sina & Christoph Barmeyer (2021, p. 188), slightly amended

Let us begin our analysis by considering two possible approaches when encountering an intercultural situation, such as the one described above. One path often involves an initial emotional reaction, which may then lead to generalisations, and in some cases, even rejection and avoidance. This route is frequently taken when individuals feel misunderstood, experience anger, frustration, or believe their needs are being overlooked. In our case study, this is precisely the scenario that unfolded. Notably, the controller in our case study took it a step further by choosing not to respond, a decision that can be seen as a form of denial. These possible steps are shown in the bottom part of our expanded transactional model below.

The transactional model of communication (part 2)

Source: Based on and inspired by Bosse, Elke (2011, p. 103)

Image by Marie Seeberger (www.behance.net/marieseeberger) CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 license

Click on the image for a larger view

On the other hand, there is an alternative pathway, one that has the potential to foster dialogue and the co-creation of meaning. To tread this path, it is essential to analyse the communication process as a foundation for developing multiple hypotheses and action strategies. An initial step towards achieving this outcome involves stepping back and utilizing the communication model as a guide to delve deeper into potential reasons for the confusion.

A brief analysis

When performing the analysis, we consider the communication process as an entity and thus look at the entire transactional model of communication.

In our scenario, we have two communicators who are expected to collaborate closely, with one situated in the subsidiary and the other at the parent company. This context of action is firmly rooted in the realm of business. Their primary mode of communication is through email, a written form of correspondence. It's worth noting that the language used is German, even though it may not be the lingua franca within the company. The extent of the person in France's understanding of written German is unknown. The urgency of obtaining the figures adds an element of psychological pressure for the person in Germany.

Expanding our model, we recognize that both individual personality traits and cultural backgrounds play a pivotal role. Regrettably, the information available does not provide a comprehensive view of the communicators' personalities. Nevertheless, it's plausible to assume that the individual at the parent company values clarity and directness. Given his cultural background, he likely belongs to the German or English-speaking community. He appears to be male and accustomed to formal modes of addressing colleagues. Specific details about his current situation or nationality are not disclosed.

Comparatively less information is available about the colleague in France, although her reaction hints at familiarity with a different communication style. She is female and shares membership of an English-speaking community with her counterpart. It is possible that English may not be their first language. Both are employed by the same company but occupy different levels and functions. Whether she is a French national remains uncertain.

Turning to the encoding and decoding processes, it's essential to remember that this case study offers a mere snapshot of a broader communication process. Details such as the length of their working relationship and prior discussions regarding requests for information are absent. Additionally, the use of email simplifies communication by excluding non-verbal, paraverbal, and extraverbal elements.

In the context of the encoding process, we can consider the following questions:

- What are the communicators' intentions?

- What are their expectations?

- How do they convey their messages?

In our case, the person in Germany needs to compose a consolidated report and requires the figures to align with his particular specifications. He communicates this by sending a formal email request.

Regarding the controller's response in France, her silence likely signifies dissatisfaction with the way she was addressed. It may also serve as a demonstration of her objection and a desire for an apology, conveyed through her simple act of not responding.

In the decoding process, the following questions come into play:

- How do the communicators perceive the responses or lack thereof?

- How might they interpret the communication?

- What are their expectations?

For the person in Germany, decoding the "silence" is challenging. Silence, as a form of communication without words, is intricate to analyse. He may perceive this lack of response as confusion or an inconvenience, or he may perceive it as non-cooperation.

As for the controller in France, she clearly views the response as disrespectful and probably interprets it as rudeness. Her specific expectations remain unclear.

Developing hypotheses

The answers derived from the analysis can help us to develop hypotheses, i.e. potential explanations for what may have gone wrong. Let's begin by examining the perspective of the individual in Germany who required the figures. One hypothesis is that he might have perceived the controller in France as being unproductive or uninterested in reviewing the figures. Another hypothesis could assume that she was too occupied to respond, possibly due to being out of the office or encountering technical issues. When the employee in Germany reflects on how his email might have been received, he might also consider that she could have been irritated by his choice to communicate in German. Upon re-evaluating his email, he may even realise that his request to "Please check them again" could have come across as an order rather than a friendly request. Additionally, he may contemplate whether his message conveyed a sense of dominance or an attempt to assert authority over the subsidiary. Another hypothesis could be that she simply reviewed the figures diligently and is confident that they are correct, leading her to feel unjustly accused. She may have perceived the email's tone as impolite, accusatory, and intimidating. Alternatively, she might have anticipated constructive verbal feedback rather than criticism or may feel her efforts have gone unnoticed.

Shifting our focus to the controller in France, and assuming she begins to reflect on her decision to remain silent, several hypotheses may arise. For instance, she might consider the possibility that the controller in Germany was rushing to complete tasks before leaving the office and inadvertently forgot that he was composing the email to his French colleague in German. Alternatively, he might have been running late for an appointment but wanted to address the request promptly. The pressure from superiors might have contributed to the tone of his message. Considering his personality and cultural background, she might also acknowledge that he probably prefers direct and fact-oriented communication, which might explain his approach.

Action strategies

The hypotheses we develop here serve as the foundation for considering various action strategies, which we can then implement on a trial-and-error basis. This approach acknowledges the inherent uncertainty in our reflections and the corresponding action strategies. It underscores the need to remain open-minded about others' behaviour and the importance of our willingness to adjust and reflect.

Since the person in the German office is the one who requires the figures, he is likely to take the initiative. If he suspects that the controller in France may not have received the email or overlooked it, he may choose to resend it initially. If this does not yield the desired response, he may step back and contemplate a more comprehensive approach, which we could also call a strategy.

Effective action strategies often involve multiple interconnected activities and moves. Ideally, after contemplating the silence from the French office and developing various hypotheses, the individual in the German company may recognise the misunderstanding and its potential causes. One action strategy could involve initiating a phone call to express his supposition that his message may not have been interpreted as intended. This conversation could serve as a platform to inquire about the colleague's assessment of the figures, fostering a dialogue aimed at exchanging information and establishing common ground.

On the part of the controller in France, she may choose to set aside her negative feelings, review the figures, and resend them with a brief note. She might also consider that her counterpart at the headquarters is unlikely to have had ill intentions and opt to call him to discuss why the figures were deemed incorrect. Such a trial-and-error approach is helpful in situations where minimal repair work is needed or when relational aspects between individuals are not a primary concern.

Like other models, the expanded model of communication is not a perfect reflection of reality. It would be misleading to assume that, after the analysis, developing multiple hypotheses automatically and necessarily leads to the solution. Also, the action strategies chosen may not always be well-received by the other communicator.

Nevertheless, the model enables us to critically examine and reflect upon our own behaviour and the behaviour of others in complex communicative events that may appear confusing. It helps us to explore different interpretations and form a solid basis for addressing misunderstandings and actively co-creating meaning.