When routine actions are accepted and shared by all, we can assume that the people involved have gone through a process of negotiation. A negotiated culture thus indicates a reciprocally and collectively formed culture that develops out of a communication process between all parties. It is linked to the interplay and process between action, reaction and adaptation, leading to the construction of reality. The experience of Marie and Jo may illustrate this:

When Marie and Jo started to work together, they realised that they had very different communication styles. Whereas Marie grew up learning that it is polite to wait until the other person finishes his or her sentence, Jo is a person who emphatically interrupts Marie. Getting passed her initial irritation with Jo's behaviour, she decides to talk to him about it. This is when they realise that Jo perceives his communication style as polite because by interrupting and being supportive of what Marie says, he wants to show his consent and appreciation. Understanding that interruptions distract Marie, especially when she wants to explain and talk about complex issues, Jo happily agrees to adapt. They agree that when Marie wants to explain something in more length and wants to be listened to without being interrupted, she simply says so. At times, however, Jo falls back into his habit, and whenever it is important to Marie she jokingly reminds him of their agreement.

For Yoko Brannen (1998, p. 12), the term 'negotiate' "is used as a verb to encourage us to think of organizational phenomena as individual actors navigating through their work experience and orienting themselves to their work settings. Focusing on culture as a negotiation includes examining the cognitions and actions of organizational members particularly in situations of conflict, because it is in such situations that assumptions get inspected." From such a perspective, negotiation can be identified as construction and reconstruction of divergent meanings and actions by the actors.

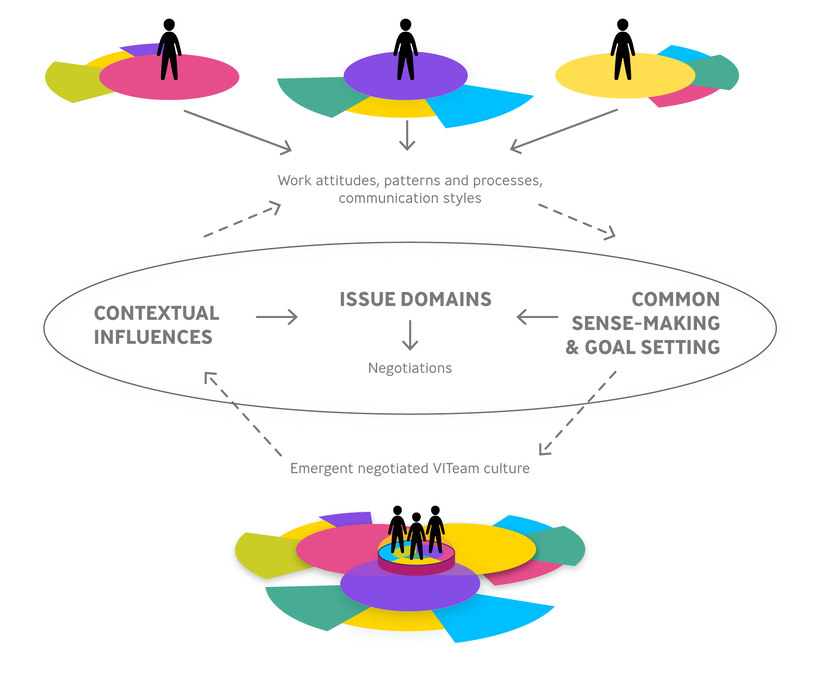

Such a negotiated culture requires different steps to be acknowledged, as the illustration below indicates. People meet and bring with them their cultural orientations, which reflect their individual social histories. They experience, therefore, a different set of meanings and have disparate behavioural routines. From these differences, issue domains that are perceived as confusing, difficult to deal with or incompatible can be delineated after a certain amount of time working together. These issue domains need to be acknowledged and respected so that they can be deliberately addressed and taken into consideration. If we recognise that culture is embedded in personal social histories, then it is clear that ensuring common meanings regarding the issues and goals at stake is vital. One step in this direction would be to acknowledge the collectives to which the actors belong when they are relevant to the task. Because the interaction takes place in a specific context, which can be influenced by relationships of hierarchy, power and dependence, these need to be taken into account and addressed.

Out of this interplay of shared sense-making, goal setting, identification of issue domains and contextual influences, the process of developing a culture that is appropriate to the circumstances, goals and group members’ cultural orientations can emerge. In the process of such a negotiation, common meanings as well as rules and behaviours which are acceptable to all should be established. In this way the parties involved create a common basis for communication, cooperation and collaborative working.

Source: Based on Brannen, Mary Yoko & Jane E. Salk (2000, p. 457)

Illustration by Julia Flitta (www.julia-flitta.com/)

A negotiated culture is, as with any culture, fluid, which means that in the course of working together renegotiations may need to take place, followed by a refinement of the culture. A negotiated culture is therefore the outcome but also the beginning of a process.

Establishing a common basis for interaction and thus a common culture requires time, understanding, creativity, as well as the willingness and capacity to communicate and dialogue. People therefore need to possess the openness with regard to setting aside the time and energy needed for a culture to develop. During this process however, the level of unfamiliarity or strangeness experienced by the actors may differ. And finally, the way the negotiation process proceeds also depends on the complexity and relevance of the work domains that are involved and need to be addressed.

For example, in a work group in which all members are already experienced and confident in using English as a lingua franca, there is little need to debate which language to use. This is different when a newly established workgroup consists of some people who are not used to speaking English and others who are fluent and accustomed to its use. In such a constellation, language is an important issue domain. Here actors may come up with a negotiated solution whereby those who do not feel comfortable speaking English can discuss in their mother tongue. An alternative solution might be to agree to have somebody summarise important issues in a language other than English to make sure that all contributions are understood. Yet another option could be to ensure that important issues are translated or interpreted.

The outcome of such a negotiation process cannot be predicted but generally speaking several options are possible:

Complementing each other:

This refers to pooling resources such as knowledge and skills with the aim of achieving a better outcome through their combination.

For example, one person may have very good technical skills and another is good at writing reports. In this case they may simply decide that each of them simply contributes in the area of their competence.

Adaptation:

Adaptation is the ability and willingness to adjust one's own behaviour and accept different and new behavioural patterns or work approaches that might be more appropriate to the group’s situation and goals. One reason to choose such an approach could be that those who have greater access to particular resources can be more effective in this way.

An example is the case of Nick. He used to be a working student in an international company where he benefited greatly from the regular feedback he received. When he started his internship he was surprised that he never received any comments regarding the quality of his work. When he talked to his supervisor about this, he was told that his task was not a common one and that his boss did not have time to devote to it. As he was an intern, Nick felt he had no other choice than to accept this.

Finding a middle way or compromise:

In this process, the outcome of a negotiation emerges through all or some of the people involved ‘giving in’ to a certain degree, whilst integrating new practices. We might say they are 'meeting in the middle'.

Consider Lina who is concentrating on writing a report that needs to be completed today when she gets interrupted by Leo, the intern in their department. He asks a lot of questions and wants to be shown how to collate his Excel lists correctly. Because they talk about their different needs, they manage to come to a compromise whereby Lina spends time with Leo showing him Excel, while Leo helps Lina to format the report so that she does not lose time.

Novel ways of interacting or developing synergies:

This is a constructive approach whereby people search for new and innovative ways of working together. It is different from complementary approaches because it focuses on the added value of working together and the creation of something new through a process of combining attributes. Novel approaches can develop when social interaction among team members triggers the production of new ideas and products that the team members would not have been able to generate on their own.

The following is a quote from an internship report illustrating value creation:

"Another example where the international team added value was when we were all working together on one analysis. While I went into too much detail and was wasting a lot of time through my search for perfection, my colleague reminded me of all the tasks that were still pending. First, I thought this was not the way to go because we were not taking into account all of our information. However, in the end I learned that it was good to gain an overview of all the numbers. The way my colleagues worked was quite interesting because they defined the result they wanted to achieve and then found a way to get to that result, while I tried to do everything step by step, moving towards the best possible result. By using a mix of both approaches we produced a very meaningful analysis in the end and our boss was very happy with the result..."

What this quote highlights is the fact that time needs to be set aside for an open process of value creation.