There is no one single definition of intercultural competence. Equally, there is no one definitive term to describe it. In fact, the term may produce a wide range of associations such as intercultural communication, cross-cultural awareness, intercultural sensitivity, cultural intelligence, adaptation and possibly even global citizenship. In our conceptualisation of intercultural competence we acknowledge a dynamic understanding of culture and pursue a practical approach. Our understanding of competence therefore needs to be linked to the behaviour a person exhibits. This means our understanding of competence involves the development of a behavioural repertoire. This could be viewed as the cultivation of a range and variety of behaviours that are capable of achieving positive collaborative outcomes.

This kind of thinking is at its core similar to the definition of competence outlined by Kurz and Bartram (2002; p.230) who state that: “A competency is not the behaviour or performance itself but the repertoire of capabilities, activities, processes and responses available that enable a range of work demands to be met more effectively by some people than by others.” A competence can thus be understood as enabling us to do something. Kurz and Bartram use the example of a musician who has a repertoire of styles and skill areas which enable him or her to perform in a specific way. They call the performance “the choreographed stream of behaviour”. The musician’s competence refers to his or her ability to perform and transfer knowledge and skills from one job task, i.e. context to another.

If we apply this analogy to interculturality and thus situations which lack familiarity, plausibility and routine actions, then we can conclude that we need competencies that enable us to ‘create a sense of normality or familiarity that neutralizes the mechanisms that encourage stereotyping, inducement of anxiety, negative attribution and the creation of in and out-groups that the intercultural space may bring about’ (Verdooren, 2014, p. 19). In other words, interculturality requires competencies which have the potential to enable those involved to create connections and a common space which can then be used to further explore and negotiate differences. Intercultural competence can then be understood as enabling us to manage interactions in such a way that they are likely to produce an appropriate and effective outcome.

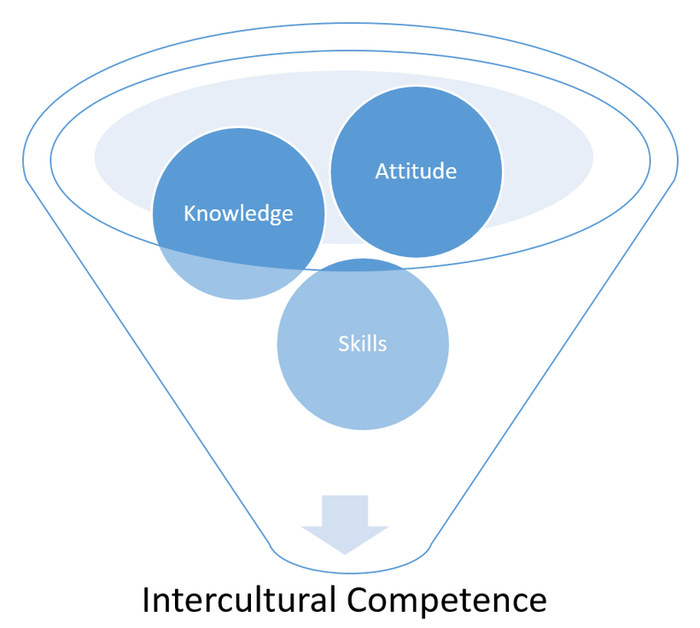

Although the understanding of intercultural competence varies in nuances, current theories and models commonly refer to intercultural competence as having three dimensions: knowledge, skills and attitude. Attitude refers to the willingness and openness to interact with a diversity of people and is thus a precondition for constructive cooperation. It can also be argued that awareness of culture as an influencing factor on people’s behaviour and communication style is closely linked to attitude. For example, we may have an open attitude but if we are not aware or sensitive towards issues that affect a given interaction sequence, then the attitude itself does not help very much in itself. Awareness includes aspects such as openness, empathy, curiosity and flexibility. The skills dimension refers to the ability to act. It includes observing, evaluating, changing perspectives, reflecting, and processing acquired knowledge. Knowledge can be knowledge with regard to social processes, knowledge regarding how other people see themselves as well as general geographical and culturally specific knowledge.

Although at times it is difficult to delineate the three dimensions and we could justifiably contest that all three are interconnected, conceptualizing intercultural competence in such a way is helpful because it can be used as a framework to evaluate what we have already achieved and define areas we want to develop further. Let us look at a very straightforward example. You might be very interested in completing an internship in Shanghai and therefore want to prepare for your journey. To do this you might well start reading about China. You then learn how to eat with chop sticks because these sources tell you that this is the common way of eating in China. By learning and exercising how to eat with chop sticks you develop the expertise and skills. In this way the knowledge part is linked to general country level information, whereas the skills part relates to the expertise and the attitude aspect to your willingness and openness to explore. And because you also reflect on your knowledge and know that this information should not be generalised or taken as absolute, you are only slightly surprised that when you are invited to eat with your new boss, you are given chop sticks, a spoon as well as a plastic serviette. On asking when to use the plastic serviette, you are told that you can use it to help eat the leg of duck using your hands.

The interdependence of the three components is equally illustrated by the following example: You may have learned that in many cultures, a meeting begins with a lengthy period of smalltalk. However, simply knowing this does not teach you how to deal with such situations if you are not familiar with them. Furthermore, you also need to have the willingness and openness to manage such situations well.

With this as well as the three dimensions in mind, let us explore your competence repertoire.

Task: My intercultural competence repertoire

Think back to the sessions you have already worked on, your life experiences and social history. Using keywords, note down what kind of cultural knowledge you have acquired and what kind of skills you have already developed. Since attitude and awareness are linked to motivation or inner disposition and are at the same time difficult to teach and learn, simply note down what you associate with these terms.

Linking these three dimensions provides the prerequisites required to develop a common basis for understanding and negotiate a common culture. This also means that intercultural competence supports the ability to develop and form an intercultural space.