You already encountered the notion of multi-collectivity in the first session. Now we will dig deeper and explore your membership of various collectives. Let us start by watching a short video about Emil and his collectives.

As the video shows, culture always refers to a plurality of people, i.e. more than one person, and is therefore a group phenomenon. Such groups may be as small as a local football club or as large as an organisation or a nation. We can, in fact refer to an entire society as a cultural group and also maintain that in each society there are smaller groups that share a lifestyle and other features quite distinct from those of other members and groups. This is why Hansen (2009) introduces the term ‘collective’, a term he uses for groups sharing a certain amount of commonalities and consistencies.

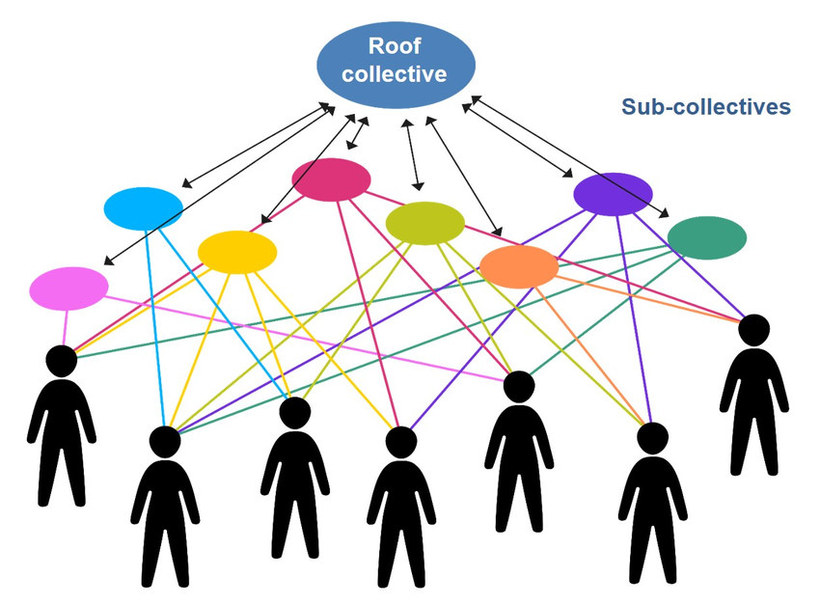

As an example, Hansen (2009) refers to Germany as a roof collective and to the local catholic community as a secondary or sub-collective (cf. Hansen, 2009, p. 82). The major difference between the two is that sub-collectives are made up of individuals and roof collectives are made up of sub-collectives. A tennis club is a sub-collective because it consists of individual members as opposed to the German federation of trade unions for example, which is made up of several single unions and thus a roof-collective. We could also call this an “umbrella collective”.

The notion of collectives allows us to understand how we feel a strong affiliation to a variety of groups at the same time and are therefore multi-collective people. These collectives can be linked to a profession, migration history, kinship, language, interest, ethnicity, occupation, world views, institutional membership or socio-economic or regional characteristics. In addition to these, we also need to acknowledge further variables that influence social relations and behavioural patterns. One is, for example, the influence of social media. And some other variables, which have traditionally received less attention such as gender, social status and power structures should not be overlooked. These examples show that some of our affiliations are given by birth, some are developed and others are intentionally chosen by the individual over the course of our lives. Some of the collectives that we belong to may exhibit opposing values or principles, whereas others are intertwined and can be viewed as a network.

As the figure below illustrates, people from the same roof collective can be members of the same and different sub-collectives. The thickness of the lines indicates that the strength of the affiliations may differ. The arrows indicate that roof collectives influence sub-collectives and vice-versa, showing that culture is dynamic, an aspect we will return to at a later stage.

Source: Yildirim-Krannig, Yeliz (2014, p. 212). Kultur zwischen Nationalstaatlichkeit und Migration: Plädoyer für einen Paradigmenwechsel. Bielefeld: Transcript.

Figure by Julia Flitta (www.julia-flitta.com)

Generally, it can be argued that multi-group membership tends to increase with the growing complexity of social systems. In particular, in complex societies people are members of many different collectives and thus combine different belongings and allegiances, a multitude of interests, roles, values and practices. People are therefore always on the intersection of a number of group memberships. These collectives may overlap but can equally be added to like a mosaic.

This also means that multi-collectivity relates to the diversity within cultures. It implies that two people who share the same national or ethnic background might have different lifestyles, views of the world and behavioural patterns.

Consider for example a rural family in Eritrea whose members have received no formal education and make a living from their land. They meet a woman in the capital who is a trained doctor, has travelled extensively and speaks English fluently. Despite their shared nationality, their views, experiences and references are likely to differ in many ways. In fact, it is likely that the medical doctor will have more in common with her professional colleagues in other parts of the world.

Considering memberships of collectives thus helps us to be aware of commonalities as well as differences within and across national borders.Another example is illustrated by a Chinese passport holder who is a member of a collective of illustrators. Some of the other members of this collective were raised in Great Britain and Germany. When they meet and communicate, their professional identification as illustrators is much more relevant than their national identity, especially because they share English as a lingua franca. In a different context, the fact of having been raised in China might be take on greater importance than the professional identification.

The arrows pointing away from the sub-collectives indicate that some members of the roof collective are also members of other roof-collectives.The classical example are people who hold two different passports or people who spend a lot of time in one country and feel a strong affiliation to that roof-collective country but equally to their country of birth.

Source: Yildirim-Krannig, Yeliz (2014, p. 212). Kultur zwischen Nationalstaatlichkeit und Migration: Plädoyer für einen Paradigmenwechsel. Bielefeld: Transcript.

Figure by Julia Flitta (www.julia-flitta.com)

By introducing culture as a group phenomenon and acknowledging membership of different collectives, we move away from considering culture solely in relation to a ‘passport identity’ or as ‘ethnic groups’ such as the offspring of Turkish migrants in Germany or British pensioners moving to France and living in a so-called ‘cultural enclave’. Instead of simply acknowledging ‘the migrant’, we can observe a large degree of variation in migration histories, educational backgrounds, length of residence, world view and economic backgrounds. Germany for example can be considered a roof-collective and people who belong to the German roof-collective may follow the way of Buddha and thus consider themselves to be members of the sub-collective of Buddhists. They share this membership with many other people in the world in attempting to follow the teachings and practices of Buddha.

The illustration below shows a person who is a member of various collectives, indicated by the different colours surrounding them. Meeting a group of people at a party, for example, might show that he or she shares their interest in Buddhism with many others.

Source: Based on Rathje, Stefanie (2015). Multicollectivity – It changes everything. Key Note Speech at the SIETAR Europe Congress (Presentation slides (stefanie-rathje.de)). Accessed 10.11.2024.

Figure by Julia Flitta (www.julia-flitta.com)

They might also realise that many people at the party share membership of the student collective. Some might be students and have an affiliation to Buddhism, which is indicated in the illustration below.

Source: Based on Rathje, Stefanie (2015). Multicollectivity – It changes everything. Key Note Speech at the SIETAR Europe Congress (Presentation slides (stefanie-rathje.de)). Accessed 10.11.2024.

Figure by Julia Flitta (www.julia-flitta.com)

The speed, scale and spread of diversity has reached previously unknown levels. People increasingly have more and better opportunities to relocate, whether it be for leisure, work, political or economic reasons and therefore increase their horizons and cultural orientations. And ideas and information are moving as well in an unprecedented level, enabling people to adapt and adjust to new and very different life styles and behaviours. The speed with which diversification is taking place and the spread of diversity is challenging our political, economic and social systems. Indeed, we are only beginning to understand the changes and challenges that are linked to these developments.

They also have an influence on our identities or how we perceive ourselves of who we are. In this context it appears to be helpful to think about what Amin Maalouf (2000, p.86) calls a ‘vertical’ and ‘horizontal’ heritage. The vertical heritage comes to us from our forefathers or ancestors and relates to our learning of traditions, local values and norms. The horizontal is linked to our age and social groups and the environment we live in which usually has a very determining influence. These heritages coexist and add to the sum of our diverse affinities and belongings. Maalouf himself was born in the Lebanon and spend most of his life in France and argued that he feels not just a belonging to both countries and their cultures but also that he is ‘the result’ of both countries. This follows the thinking that we can be home in more than one country and supports the notion that we should acknowledge multiple belongings and allegiances and thus multi-collectivity.

In today’s complex societies and environments understanding ourselves as members of many and at times quite different collectives enables us to study small entities and carry out what Clifford Geertz (1973) calls a ‘thick description’ by moving away from surface and generalising level. Recognizing membership in collectives also means to depict commonalities where one may anticipate differences and thus develop a common ground for understanding among members of different groups within and across countries. It thus acknowledges the interconnectedness across boundaries, the notion of cultural adaptations and mixes as well as the diversity within societies. This is important because focusing simply on nations as a cultural signifier would not do justice to the diversity of people around us.

Task: My collectives

Which collectives are you a member of?

Name five of them and note them down in your learning journal.

Having completed this task, click on the following link to view a possible answer.

Show / hide sample answer

Other participants named the following collectives:

- My family

- My project team

- My study group

- My group in the fitness studio

- My close friends

- My sports team

- My gender

- My age

- My music band I am playing in

- My volunteers group

- My religious affiliation

- My church

- My neighbourhood

What you will realise is that some of these collectives, as for example your project team, are easy to grasp, while others, such as your gender collective, are very difficult to confine.