The quotes below are taken from emails that were part of an exchange between customers and a supplier of spare parts. Imagine that you oversee customer satisfaction at this company’s logistics department. You arrive at the office on Monday morning to find the following emails from clients in your inbox:

Think about:

- What is the actual content of the two notes?

- What feelings are evoked in you when you read them?

- If the content were part of a telephone conversation, how might the intonation alter your interpretation and how you perceive the words?

- When you read the emails, does the relationship you have with the customer make a difference to the way you interpret the messages?

- Does the number of prior email exchanges influence your interpretation of the content?

- Does the knowledge that your customer is a native English speaker influence how you "read" the messages?

Consideration of these questions can show us how multi-faceted and complex communication is. They highlight how much meaning might be contained in simple messages such as those above. This in turn underlines the relevance of analysing communication situations carefully.

In this session, we will achieve this by discussing the various components of the communication process. At the same time, we are aware that examining them separately has its limitations and serves only for the purpose of analysis, since ultimately, they are all intertwined elements of the communication process.

In essence, we can delineate eight elements of the communication process:

- the communicators or people involved

- the forms of communication

- the encoding and decoding process

- the medium used

- the type and amount of noise

- the context of action

- the response of the communicators and their interpretation

- the co-creation of meaning and outcome of the communication

The following example shows the different elements in a communication situation:

A client and a supplier (communicators) have recently started to develop a business relationship and the supplier has just delivered to his new client for the first time (context of action). Having noticed that one item that was ordered did not correspond to the specifications, the client wants the item to be replaced. As he has been waiting for the shipment for a long time and urgently needs the item, he is quite upset and decides to phone his supplier (medium) and talk (form of communication) to him. During the phone call there are disturbances on the phone line which constantly interrupt the conversation (noise). Both communicators react in an irritated manner (response) and decide to continue their communication via email to ensure that they develop a common understanding of what went wrong (co-creation of meaning) and what needs to be done differently in the future (outcome).

Before integrating these elements into a model of communication, let us look at each of them in more detail.

The communicators

The people involved in interpersonal communication are the communicators. Viewing them as communicators takes cognisance of the fact that they both create and receive messages, and that giving and receiving is not only a reciprocal act, but one that takes place simultaneously. Think about a situation in which someone asks their supervisor for a pay rise. Even while presenting the argument, the person doing so will carefully prepare, anticipate, and design his or her utterances, whilst observing the supervisor’s reaction. The supervisor may signal concern or surprise and may, at a later point in time, respond verbally to the request. So, while speaking, both continuously shape their speech acts and orient themselves towards the other. This also means that there is an interdependence between the communicators.

The forms of communication

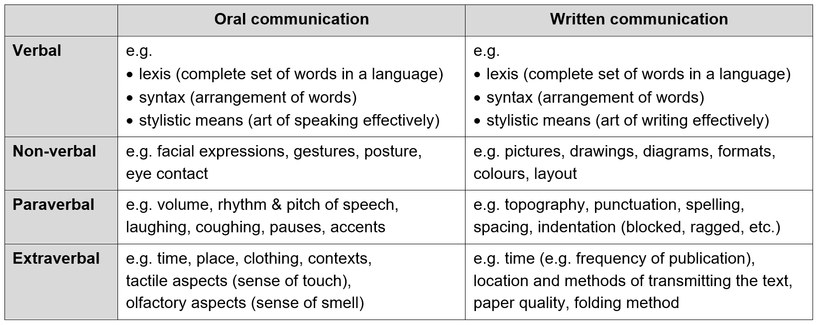

Communication is a process during which people interact while using different forms of communication to create meaning. A basic distinction can be made between oral and written communication. Within these categories, a further distinction can be made between verbal, non-verbal, paraverbal and extraverbal forms of communicating as the following chart shows.

Different realisations of the four communication components

Source: Bolten, 2015, p. 23, amended and translated

Generally speaking, we communicate using signs and symbols that stand for something. Verbal signs and symbols, no matter whether they are spoken or written, refer to the words of a language but also to aspects such as the manner of speaking, the way words are arranged, and the style and ordering of sentences. In contrast non-verbal signs and symbols relate to the language of the body, including gestures, facial expressions, and body posture when engaged in oral communication. In written communication we can also observe non-verbal communication. In this case it is represented by pictures, drawings, and diagrams, for example. Paraverbal communication or paralinguistics include aspects such as loudness, accents, volume, and silence. As the term suggests, extraverbal communication relates to the time and place a communication takes place, but also includes our sense of touch and smell when communicating face to face. In written communication, extraverbal communication refers to time, for example the time of publication, but also to where the text is transmitted and other aspects such as the folding of the paper, for example.

Although meaning and affect is created through the interaction of verbal, non-verbal, paraverbal and extraverbal signs in oral and written communication settings, for analytical purposes they are will be dealt with separately in the following.

Verbal forms of communication

When thinking about verbal forms of communication, language is usually the first aspect that comes to mind. Language can be defined as a system of signs. The signs of a language are known as words, which stand for and represent things. For example, the three letters “d o g” constitute a word because at some point in time people agreed that this word should stand for a domestic animal. But because shared meaning depends on all people involved, the meaning and connotation of what a dog is, may vary. Some people may know a dog as a pet or even a family member. Others may view a dog as a working animal used to round up sheep and cattle. Yet others may simply see dogs as dangerous animals. This knowledge, which is transmitted and backed up by evaluations from our social group, influences our perception fundamentally.

Words are combined in a systematic way and following specific rules and social conventions. Social conventions tell us which signs, in this case words, we should use and how we should combine them to form sentences and communicate in a meaningful way. When we combine words to form a sentence, we apply the linguistic and grammatical rules that we are accustomed to. These practices have developed over the course of time and continue to change and develop further.

For example, among the German speech community it has become customary to use the word “Handy” for a mobile telephone or cell phone, although in most European and some other languages the word “mobile”, or “smartphone”, is common. Among the English-speaking community, the word “handy” commonly means “convenient to use”. What this example shows is that meaning is linked to the social conventions that are known and accepted by its users.

The use of the words “yes” and “no” is another case in point that is frequently mentioned as a source of misunderstanding. Apart from the meaning of “yes” as an affirmation, Hoffman and Verdooren (2019, p. 160) refer to other possible meanings of the word. They argue that it can also mean “Maybe”, or “I’ll think about it”, or “I hear what you are saying” or “Go on with your story”. The latter meaning of “yes” is called a verbal backchannel, where the person receiving the message intends to convey politeness and attention. An explanation for the variety of meanings of “yes” and “no” is that the answer in such cases is strongly linked to the relationship the communicators have rather than the content level (Hoffman and Verdooren 2019, pp. 160f.). For example, a person might be asked by his or her boss who has a preference for direct speech “Would it be possible for you to come in on Saturday for an hour or two?”. Instead of responding “I am sorry, but I will not be able to make it”, thus following their boss’s preferred communication style, may say “Yes,…” while in effect being unable to fulfil the request. The person may say “Yes” because he or she does not want to disappoint his / her boss and may use the “Yes” in the sense of “I will try but most likely I will not be able to make it”.

However, words may not just have different meanings, they can also stand for different social conventions, as the following example from two work colleagues highlights:

The lexical or literal meaning of the sentence “Why don’t we have lunch together?” is easy to understand. However, the social convention behind the sentence could be that it is just a polite way of saying “I need to leave now and I want to say something that conveys connection and smooths my departure”. Considering the response, it probably meant that they might eventually have lunch together in the foreseeable or non-foreseeable future. The same may be the case for the sentence “I’ll talk to you later” with later meaning “some other time” rather than later during the day or the week. The social convention behind this is likely to be that of a polite marker in order not to disappoint the conversation partner and smooth the social interaction.

Non-verbal forms of communication

Apart from communicating using language, we can equally communicate non-verbally. Whereas verbal signs refer to spoken and written words, nonverbal signs are cues or signals that are transmitted without the use of vocabulary. When speaking, we choose words to convey meaning and these are accompanied by our bodily movements, facial expressions, and hand gestures. These non-verbal signs influence the meaning we assign to the words used. Non-verbal signs can supplement a verbal message, underline it or at times contradict it. For example, we might meet a friend and ask her: "How are you doing?", upon which she might reply: "I'm fine, thanks", even though her sunken face tells you otherwise.

Even for those who place considerable emphasis on verbal communication, the fact that non-verbal cues play a significant role in communication is inescapable. In contexts in which verbal transmission is impeded, non-verbal communicative codes based on gestures, facial expressions, body postures and distances, as well as paralinguistics become increasingly important. In fact, it is commonly argued that non-verbal communication ultimately has a greater impact on the message conveyed. It is therefore understood to be a language that is as crucial to meaning as it is difficult to steer.

For example, expressing one’s feelings in a non-verbal way is very common and there are many ways of doing so. Some people may openly, expressively, and directly show their happiness, surprise, or anger. In an attempt to emphasise a point, express dissatisfaction etc. the entire range of human emotions might be displayed. On the other hand, some people may be much more restrained in expressing their emotions or even try to abstain from showing them openly at all. The way we express our feelings and intentions in a specific setting is strongly influenced by social conventions but also our personality.

Facial expressions may be interpreted quite differently by individual communicators. A smile could be perceived as a sign of joy or affinity when meeting somebody or as self-confidence. However, it may also be interpreted as an expression of doubt or even hostility and interpreted as a malicious grin. Equally, people may confuse others if they smile after having made a mistake. Observers may not connect the smile to the social practice of saving face, which prevents people from letting emotions govern the situation.

The following images show examples of facial expressions. Look at the images and think about which emotional state they may display.

Facial expressions for different emotions: fear, contempt, sadness, happiness, surprise, anger, disgust

Photographs by Elena Martou

Another example is eye-contact. Eye contact can be perceived as a sign of attention, respect or sincerity and honesty. If this is so, people who look away or lower their head to avoid eye contact when talking or being addressed may accordingly be perceived as disinterested, disrespectful, or inattentive. However, the intention may be very different. For example, a young adult lowering his head and avoiding direct eye contact in front of his boss may behave this way to show respect to a superior. It is therefore important to develop an awareness of one’s own and of other people's perception of different facial expressions.

A further aspect of body language is the spatial distance between people, also known as spatial zone or personal distance zone. There are social conventions and expectations linked to this concept. In particular, our unconscious expectations become very obvious when our spatial zone is perceived to have been violated. If, for example, our personal distance zone is set to 40 to 50 cm, and this does not correspond with our communication partner’s spatial expectations, then our behaviour may be perceived to be intrusive, impolite or even intimidating. Negotiating a comfortable, mutually accepted personal distance with our communication partner is therefore vital.

The personal distance zone is closely linked to contact behaviour and touch. People who like to stand apart may also be confused by a physical touch such as patting on the shoulder, the arm or the hand. Greeting each other by shaking hands is also a touching gesture and is perceived very differently depending on the expectations of the receiver.

Task: My personal distance zone

Choose a specific context, for example when queuing up at a shop or waiting at the bus stop, and reflect on your preferred personal distance zone by gradually moving towards the person waiting with you. When do you start to feel uncomfortable? Do you think that the corona pandemic, but also such factors as the gender and body height of the person you are interacting with influence your preferred distance zone? How about the preferred personal distance zone of the other person: Is it similar to or different from yours? How can you tell?

Note down your thoughts in your learning journal.

Para-verbal forms of communication

Apart from verbal and non-verbal communication, we need to add paraverbal communication or paralanguage to our repertoire of communication. Paraverbal communication refers to those qualities which accompany speech and include, for example, our voice’s pitch, rhythm, and tempo, as well as pauses, articulation and resonance. It also includes vocalisation such as laughing, crying, yelling and throat clearing. Some researchers also include vocalisations such as um, ah, ooh, and uh in the repertoire of paralanguage, whereas others refer to it as verbal behaviour. Being sensitive to paralanguage and how it can influence communication can help to improve our common understanding.

Social practices influence the use and interpretation of paralanguage. For example, speaking loudly during an ordinary conversation may be perceived by some as showing strength and sincerity, by others it might signify authority, arrogance, or impoliteness. People who use vocalisations such as um, ah, ooh, and uh may be perceived as showing interest, attention, acceptance, or confirmation. and support. Others, on the other hand, may simply perceive this usage as a sign of uncertainty or weakness.

Given the increasing use of English as a lingua franca, the impact of pronunciation and accent as part of para-verbal communication have become increasingly important. These are very distinct markers of belongingness to social groups. Therefore, not only do they play an important role in how we are understood, but they also affect how we are perceived and judged in a social context. There is, for example, ample evidence to support the phenomenon that people whose accent is evaluated negatively are disadvantaged and that an accent which is perceived positively can lead to positive discrimination.

Task: Accents

Watch the short YouTube video on accents and think about whether you have been in a situation in which your accent has been perceived positively or negatively.

Video: Accents

Source: The Leadership Conference: "Accents" (Fair Housing PSA, sport produced by the Ad Council, HUD, and the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights Education Fund), 2008, URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?embed=no&v=84k2iM30vbY, accessed on 2.6.2023

Extra-verbal forms of communication

The last level of communication to consider is extra-verbal communication. Extra-verbal communication refers to what can be seen and observed, touched and even smelled. It also incorporates the place, participants’ clothing, and the context in which communication takes place. Some professions, roles or companies require either explicitly or implicitly a specific style of dress from their employees. These could be, for example, priests, police officers or businesspeople. Although there are some overlaps in extra-verbal and non-verbal communication, one could argue that extra-verbal communication emphasises messages that are intentionally sent such as drawings, graphic design, illustrations, and other visual elements. In contrast, non-verbal communication is commonly unintentional.

During the actual communication process, the different forms of communication intertwine and cannot always be separated precisely. They appear simultaneously in communicative acts, where they influence each other and ultimately come together to construct meaning.

Task: At a hotel reception

You are going to watch a YouTube video in which a customer talks to a hotel receptionist in two sequences. First, we would like you to simply listen to the conversation without watching the clip (we recommend minimizing the browser window, switching to another browser tab or switching off the display). Evaluate whether and to what extent there is common understanding between the speakers. In your learning journal, note down three examples of sequences where communication was successful or unsuccessful and argue why you chose them.

In a second step, watch the video clip and assess the non-verbal aspects of the communication you observe in the video. Identify three examples of this non-verbal communication that might hinder the creation of a common understanding between the customer and the receptionist. Note these down in your learning journal as well.

Also note down two examples to show your understanding of the para-verbal and extra-verbal levels of communication.

Video: Negative nonverbal communication

Source: TheServiceChannel: Negative nonverbal communication, 2013, URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?embed=no&v=N7lGqmZprx0, accessed on 2.6.2023

The encoding and decoding process

For communication to take place, thoughts and ideas need to be first encoded and subsequently decoded. Encoding refers to the process of turning thoughts and ideas into non-verbal or verbal codes so that they can be passed on. When we encode, we select and arrange verbal and non-verbal signs, following the social conventions we are familiar with and what is considered appropriate and applicable in a specific situation.

Imagine student June, who walks across the campus and sees a fellow student with whom she has become very friendly. She sees him smiling at her. This is likely to be a conventionalised sign and social practice from his language community that expresses a friendly greeting. In contrast, other social conventions and practices may include calling out “Hello!” across the campus or putting our hands in front of our chest and bowing.

Decoding refers to the process by which a communicator converts or translates the codes received into meaning. In a similar way to the encoding process, the interpretation and thus the meaning that the receiver attaches to the codes received depends on a variety of factors. These factors include the common conventions of the collectives that the receiver is a member of. The example with June highlights this. She may, for example, perceive the smile as inappropriate and feel intimidated by this non-verbal behaviour.

My internship abroad

Patita's experience as an intern is another case illustrating the encoding and decoding process. On one of the first days in her new environment, she sets off to do some grocery shopping. Not being able to speak the local language, she decides to point at the products she needs. She also wants to buy two eggs and indicates this using her fingers. To her surprise the shop keeper attaches a different meaning to her showing two fingers and in the end Patita ends up buying eight eggs. In this case the intern and the shopkeeper were not able to encode and decode their message in a way that resulted in the same meaning for both parties. Many weeks later that Patita learned that there are multiple systems for counting with your fingers.

Task: Counting on your fingers

How do you count to 10 using your fingers? Do you start with your thumb or your index finger? Do you start with the right or left hand? Do you start with your hand closed or open? Now watch the BBC video and acquaint yourself with one system which allows you to count to 20.

Video: Counting on your fingers

Source: BBC Reel: How the way you count reveals where you're from, 2021, URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?embed=no&v=g9S6qD_Wylw, accessed on 2.6.2023

The medium used

The medium can be seen as the vehicle through which the information travels between communicators. It is therefore the means of transmission. Verbal and non-verbal signs such as words, symbols and sounds are such vehicles. We observe people’s facial expressions and we read text. We use our five senses, such as our eyes to observe, mouths to speak, hands to write and skin to feel, ears to listen and nose to smell. It is essential that we acknowledge that in face-to-face communication all of these senses are active, and our verbal communication is accompanied by facial expressions, gestures, vocalisation, clothes and many more aspects when we exchange messages. It also means that in a communication different media are active. From a technical point of view, communication media include digital tools that support communication such as “rich media”, which refers to video and audio conferencing for example, as well as “lean media”, which includes emails, instant messages and letters. When communicating through lean media we lack para-verbal signs and cues and cannot immediately perceive the full reaction of the recipient to our message.The type and amount of noise

Noise refers to any interference that impedes our ability to communicate well. It distracts the communication process and can emanate from internal or external sources. Types of noise discussed here include environmental or physical noise, physiological noise, psychological and semantic noise.

Physical noise relates to environmental obstacles that can easily impede the communication process. For example, a passing car, the baby crying next door, the noise of the incoming underground train, the sound of heavy rain or loud music might all interfere with our telephone conversation. Even an annoying whisper or the noise of paper sliding to the ground might disturb us in a focussed exchange.

Physiological noise relates to the physical condition of the communicators. For example, a strong headache can act as a barrier to communication. Sneezing or coughing can equally distort a conversation, or you may not have eaten all day and your empty stomach distracts you.

Psychological noise is an internal noise in your head which keeps you from listening well. Such noise may relate to thoughts about something else that occupies you, or a personal bias you may hold against the communicator. Another example might be when you feel that you are not being given the chance to speak because somebody keeps talking and you are desperately looking for an opportunity to interrupt.

Semantic noise refers to disturbance in the transmission of a message due to complex and complicated language such as technical terminology, pronunciation differences, ambiguous words or different meanings of words. All these issues make it difficult for the receiver to grasp the meaning of what is being said. The communication between a patient and their doctor could suffer from semantic noise if the doctor uses medical vocabulary that the patient finds difficult to understand.

The context of the communication

Communication does not take place in a void since people always communicate in a specific setting or overall context, which we call the context of action. Context is a crucial factor that influences the communication process since the way we communicate is situational. What occurs in communication is bound up with such factors as time, space and physical surroundings, as well as the roles, status, and the relationship between the communicators.

Consider the following sentence: "You look great" being said in the following situation:

- by a woman saying this to a man at a party

- by a doctor meeting his patient after a lengthy period of recovery

- by a woman meeting her friend after having been to the hairdresser

The words remain the same but each of the three situations creates a different sense of meaning due to the context.

The communicator's response and interpretation

Response is the information we constantly receive and send as a reaction to what has been said or written. We could call this “feedback” or the feeding back of information to the initiator. This is a constant stream of information, allowing our counterpart to judge and interpret the communication while it is taking place. The response to a message, and its interpretation, are therefore important components of the communication process because they allow people to monitor their performance. For example, we may smile at our boss as she expresses her satisfaction with our work or shrug our shoulders when we are being criticised. As such, feedback can be positive or negative and we can use all our senses to receive and send out feedback. The recipient’s response exerts an influence on the sender as it gives the communication sequence its dynamic nature. It is also how we negotiate, develop and exchange meaning.

The co-construction of meaning and outcome of communication

We have already encountered the notion of shared meaning in this course. In general, meaning refers to what a word, gesture or expression refers to or represents and how it should be interpreted. We usually take it for granted that our words and other signs that we use to pass on thoughts, feelings and attitudes are conveyed and understood in precisely the manner we intend. However, this is not necessarily the case.

We also argued that communication is contextual. This means that the context or the specific environment in which communication takes place has an influence on the choice of words as well as when and how you speak or write. When we enter our boss’s office and ask to go on sick leave we might say “Please accept my apologies, but I have a severe headache today”. However, when talking to our colleagues in the break room, we are more likely to say, “Oh damn, I feel awful…I have such a lousy headache today”. Apart from how the sender chooses the words he or she wishes to communicate, the environment or context also influences the interpretation of what is communicated. It can even add meaning to the message or discern what a particular word means. The following email is an example.

It reads:

She has arrived.

Rachel Hogan Murray

6 lbs 7 oz

1:06 am

You may be able to interpret it, guessing that somebody is announcing the birth of a child to be named Rachel, who weighs 6 lb 7 oz and was born at 1:06. We can do this because it is a social convention to add the weight and time of birth to such an announcement. Knowing more about the context, in this case that the mother was expecting twins and going through a difficult pregnancy gives the message additional meaning, which a friend expressed by responding:

“OMG! Congratulations. You were so very right when you wrote Happy Day.”

This means that in communication, meaning is not inherent in words alone, but is affected by a whole range of factors, including the situational context. We could also argue that there may be a gap between what the speaker wants to convey and what is received. And it is this gap between what is interpreted and what is meant that needs to be closed or at least narrowed for communication to be perceived as successful and satisfying. It is like a missing link that is a precondition for the action which follows.

We can see from the above that communication is interactive, or in other words it is an ongoing process of sharing, exchanging, developing and coordinating meanings. Both communicators are actively and continuously involved in the interaction process and thus mutually influence the communication and its outcome.

For example, you might enter your office and say “Good morning” to your colleague with a smile on your face. You might be smiling because you are remembering the positive outcome of a negotiation you were involved in together. Seeing the smile, the other person may raise their thumb to show agreement, which you interpret as confirmation. This could make you smile even more and encourage you to say “we really did a good job yesterday!”. This highlights the interactional aspect of communication, which involves a move and countermove by the communicators while they actively engage in the joint production of meaningful interaction. Here it is obvious that the verbal and non-verbal signs are understood in the same way and are congruent.

However, this is not always the case. For this reason, we need to be conscious of and enquire about meaning. Whenever there is a missing link, extra effort is required to co-create meaning. Co-creating is understood as the joint construction and development of meaning or of a shared conception of how a message should be understood. In other words, communicators are required to make sense of their interaction through a process of negotiation. The outcome of such a negotiation could be that:

- The verbal and non-verbal messages exchanged mean the same or very similar things to all parties involved in the communication process.

- Everyone understands how words are being used and how each party differs in the way they use them.

- The communicators have developed a common understanding, enabling them to understand each other’s perspective well enough to be able to accept it.

The goal of communication, i.e., to arrive at a shared set of meanings, may not always be achieved. If we feel misunderstood, we may simply walk away and grumble to ourselves and, as a response, refuse to cooperate. Here, where the co-creation of meaning fails, we might consider this to be “unfinished business” because we do not know whether or when the communication sequence might be continued.

Viewing communication from this perspective suggests that communicators are mutually responsible for the outcome of their communication while they both transmit information, create meaning and elicit responses. It also implies that participants must arrive at some mutual agreement about the meaning of their messages in order for communication to be perceived as effective and for their relationship to be considered satisfactory. The co-construction of meaning can therefore also be seen as the groundwork and pre-condition for any actions linked to the communication process. This might involve, for example, asking somebody to do something for us.

Task: How miscommunication happens

Watch the TED talk by Katherine Hampsten and in your learning journal, note down the practices mentioned that support the co-creation of meaning and reaching a common understanding together.

Video: How miscommunication happens

Source: Ted-Ed: How miscommunication happens (and how to avoid it) by Katherine Hampsten, 2016, URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gCfzeONu3Mo&t=70s, accessed on 2.6.2023